Authorization and Standard for the Use of Force

Clear and comprehensive policies authorizing the use of force can protect officers and community members while providing important transparency and accountability.

Introduction

Authorization and Standard for Use of Force: Why are clear policies on the use of force important for police and the communities they serve?

Policies governing when officers are permitted to use force are fundamental to safe, fair, and effective policing. For decades, U.S. Supreme Court rulings that established the “objectively reasonable” standard for evaluating excessive force claims under federal law influenced policy debates and decisions around when officers across the U.S. can use force. But the court did not specify when officers are permitted to use force. Instead, the Court set a minimum constitutional threshold for liability; anything below infringes on an individual’s constitutional rights.

The Center for Racial Justice’s analysis of the law, research, and leading practices generated a set of clear threshold requirements for using force that are the bedrock principles of each of the Model Policy’s modules. This module explains how officers must exhaust all non-force options before using force. Force may only be applied in pursuit of a lawful objective and, even then, the force must be the minimum force necessary and must be proportional to the circumstances facing the officer. Importantly, an officer’s decision to use force should be evaluated in the totality of the circumstances. Ultimately, effective policing goes beyond meeting minimum legal requirements. It involves a deeper commitment to engaging with communities in a constructive manner, protecting the sanctity and dignity of human life, and fostering crucial trust.

Downloads

Policy on Authorization and Standard

Download the model policy on the Authorization and Standard for the use of force.

Download PolicyFull Model Use of Force Policy

Download the Full Model Use of Force Policy – 10 detailed policies designed to help communities implement more effective use of force policies that enhance community safety while minimizing unnecessary force.

Open Full Model Use of Force PolicyKey things to know

- An officer must avoid the use of force unless it is not possible to do so. Force may not be used until all available non-force options have been exhausted.

- Before using force, an officer must verbally warn a person.

- When using force, an officer must use the minimum amount of force necessary to carry out a lawful objective such as arresting a person, stopping a crime, or defending a bystander from the person’s physical attack.

- The amount of force used by an officer must be proportional to the situation the officer is facing. Using excessive force breaks trust with the community and is prohibited.

- Deadly force may only be used as a last resort—when all other force options have been exhausted—and it is absolutely necessary to protect the officer or another person from death or serious injury.

Understanding Policies Authorizing the Use of Force

How do policies control the use of force by police officers and what do effective policies look like?

Policies governing when officers may use force are pivotal to ensuring safe, fair, and effective policing. These threshold standards influence a wide range of police actions from the use of weapons to pursuits, deploying canines, and even managing crowds. Setting this policy standard is a significant opportunity for police departments: it offers a powerful framework to align a community’s values and its respect for human life with the operations of the police force.

The Model Use of Force Policy encourages departments to adopt a standard for the use of force that surpasses the constitutional minimum. This current constitutional minimum standard determines when an officer may be civilly or criminally liable for excessive force and is anchored by federal court rulings, specifically the landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision in Graham v. Connor, 490 U.S. 386, 395 (1989). Simply put, while the U.S. Constitution might permit officers to exercise a specific level of force without facing severe repercussions, such as criminal prosecution or devastating financial judgments, it does not automatically make that use of force an appropriate course of action.

Moreover, the mere fact that an officer’s actions can be lawfully shielded from liability does not establish this behavior as the gold standard for police conduct. Effective policing transcends the boundaries of mere legal compliance. Police bear the duty to serve their communities productively, respecting the sanctity of life, fostering trust, and upholding the dignity of the citizens they serve.

In this module, the Model Policy recommends that use of force policies set clear threshold requirements that must be met for an officer to be authorized to use force. These requirements can be distilled into four core principles:

- Officers must use available non-force options and issue a verbal warning before resorting to force.

- Force should only be employed to achieve a lawful objective, and only the minimum force necessary should be used.

- The force used must be both necessary and proportionate to the situation.

- The totality of the circumstances should be considered when evaluating any use of force.

This module discusses how these concepts are reflected in the Model Policy’s approach to the authorization and standard for the use of force.

The Graham standard

In Graham v. Connor, the Supreme Court established an “objectively reasonable” standard for assessing police excessive force that rises to the level of violating an individual’s 4th Amendment rights. [1] This means that when evaluating potential civil or criminal liability for excessive force under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, federal courts examine the perspective of a “reasonable officer” at the scene, acknowledging the split-second decisions officers often face.[2] Though the Graham Court characterized the standard as objective,[3] courts often shift the focus from the officer’s actions to their mental state, questioning if the officer’s belief was reasonable, regardless of the outcome.[4]

This interpretation provides officers with significant discretion in use of force situations, and courts and juries evaluating those force decisions after the fact have similarly broad discretion in deciding whether to impose legal liability.[5] Jurors, influenced by the Graham standard, might lean towards believing an officer's testimony, even if they find an officer's actions egregious.[6] The standard does not require the officer's belief to be correct, only that their error was "reasonable."[7]

Bias can further complicate this standard.[8] Studies indicate racial stereotypes and the internal biases they foster in people—including police officers—can deeply influence perceptions of threats. These biases, associating Black individuals with aggression, for instance, may lead to skewed perceptions, such as mistakenly assuming that a Black person is armed.[9] This in turn might bolster an officer’s claim of having a reasonable belief in the need to use force.[10] Tragic cases like the killing of Stephon Clark in Sacramento, where officers mistook a cellphone for a gun, underline this issue.[11]

Additionally, jurors' perspectives might be influenced by typical police behavior and frequent force incidents, especially involving Black people.[12] As society becomes desensitized to these events, what is considered "reasonable" can become troublingly broad. The Graham standard does not adjust for these biases, and courts offer limited guidance on evaluating "reasonableness of belief," leading to inconsistent interpretations.[13]

This lack of clarity perpetuates biases in the justice system. Officers may use force more liberally against minorities without fearing liability.[14] The Graham standard's ambiguity has resulted in fewer successful prosecutions and legal judgments against officers, even in clear-cut cases. Prosecutors are often hesitant to file charges if the officer’s mental state is ambiguous, fearing they cannot succeed under Graham. As evidence, between 2005 and 2017, a small percentage of on-duty officers who killed civilians faced or were convicted of serious charges.[15]

The Model Policy’s approach to authorizing the use of force

While the Supreme Court has settled the question of when officers are civilly or criminally liable for excessive force under the 4th Amendment, local police departments can define their own use of force standards, sometimes receiving guidance from state legislatures or city governments on these regulations. However, many of these police agencies do not appear to consider the broad range of factors that can inform use of force standards—factors like safety, accountability, public trust, legitimacy, and the shared values of the community and the police organization. Instead, they often defer to the minimum constitutional standard identified by the Supreme Court in Graham.

Yet, a growing number of police departments are recognizing the Graham standard’s limitations. These departments are adopting use of force policies that go beyond Graham in limiting when force is permitted and how officers can employ it. For example, many of the nation’s largest police departments have introduced policies restricting their officers’ use of force to only the amount of force that is necessary. These forward-thinking policies typically offer more explicit guidelines than those solely anchored in Graham. They often detail mandatory de-escalation practices and other techniques designed to minimize the need for force.

In places like California, some use of force policy changes have been propelled by state legislation. Responding to tragic events, such as the police shootings of unarmed people like Stephon Clark, California enacted a 2019 law that redefined the permissible use of deadly force by officers. It transitioned from a "reasonableness" standard to a "necessity" standard, emphasizing the importance of de-escalation tactics.[16] Policymakers are increasingly considering and pursuing these types of legislative reforms, aiming to enhance the reasonableness-of-belief standard in ways that reinforce societal values, particularly the sanctity and worth of human life.

The Model Policy embraces these trends in law enforcement and advances an approach that expands on the Graham standard. This module recommends establishing a straightforward checklist of threshold requirements that must be met for an officer to be authorized to use force. These criteria are encompassed within three broad concepts: (1) the use of de-escalation and other mitigation options, (2) a lawful objective combined with the application of minimal force and (3) an assessment of necessity and proportionality. In any given scenario, the totality of a particular set of circumstances must be evaluated to determine whether a particular use of force is authorized. Beyond these foundational criteria, the Model Policy also details specific requirements for the use of deadly force.

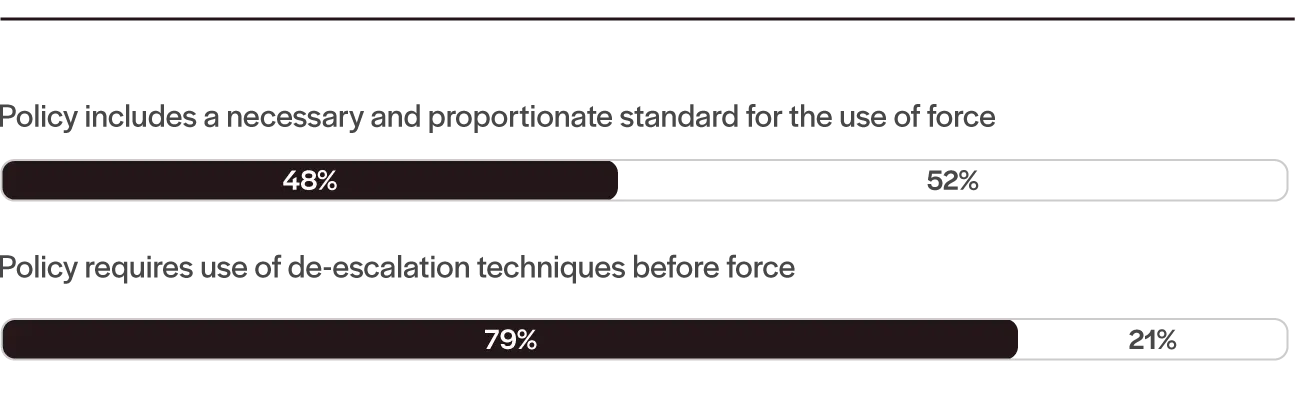

Key Force Regulations in Policies of 100 Largest U.S. Cities

Importance of de-escalation and other mitigation strategies

The Model Policy mandates that officers first exhaust the available non-force options, ensuring force is used only when alternative methods fail to secure a person’s compliance. These non-force options include de-escalation tactics, detailed in the de-escalation module. They also encompass verbal warnings, which officers should issue before using force because they can often lead to a person’s compliance. To emphasize the importance of verbal warnings in eliminating or reducing the necessity of force, the Model Policy separately highlights this strategy.

Requiring officers to have a lawful objective and use the minimum amount of force

The Model Policy stipulates that officers can only employ force to achieve a specific “Lawful Objective,” and even then, only the minimum amount the officer believes is feasible to carry out the objective. There are a limited number of Lawful Objectives: (1) conducting a lawful search; (2) preventing serious damage to property; (3) effecting a lawful arrest or detention; (4) gaining control of a combative person; (5) preventing and/or terminating the commission of a crime; (6) intervening in a suicide or self-inflicted injury; and/or (7) defending an officer or another person from the physical acts of another.

Central to these objectives is the respect for the value and sanctity of human life. Objectives like controlling a combative individual, intervening in self-harm, or defending against threats are tailored to minimize harm to all involved, including the individual in question. While the required level of force may vary, the core principle remains preserving human life.

Objectives like lawful searches, arrests, or preventing the commission of crimes, on the other hand, relate more to past, present, or prospective unlawful actions, and permit officers to act in ways that shield the wider community from such behaviors. Even the objective concerning property protection embodies the inherent value people assign to their possessions—like homes or vehicles—that are essential for well-being and livelihood. In scenarios where there is not an immediate threat to human life, officers might find lesser force sufficient, or even opt for non-physical interventions like verbal commands.

The Model Policy does not include some objectives, such as preventing escapes or countering any resistance, as Lawful Objectives.[17] Without context, the inclusion of these objectives could endorse unnecessary force. For instance, using force on a fleeing individual who is not a threat, could escalate risks for everyone involved. While fleeing in and of itself does not indicate wrongdoing,[18] if the individual presents a danger, the objective of protecting against threats would permit force.

Necessity and proportionality: critical components of an effective use of force standard

Necessity and proportionality stand as critical components of an effective use of force standard. The Model Policy emphasizes the need for both necessity and proportionality when using any form of force. It states that force should only be employed when it is essential for fulfilling a Lawful Objective and must be in proportion to the situation’s entire context.

The Model Policy suggests a more rigorous standard than the constitutional standard for legal liability in excessive force incidents. By doing so, it aims to transform the decision-making of police officers from the “reasonable officer” perspective to a more critical evaluation based on the necessity and proportionality of force in a situation, which is a more objective benchmark. It is encouraging to note that many police departments already expect more than mere reasonableness from their officers, understanding that this should be the minimum, not the ideal.[19]

Necessity and proportionality are related but distinct concepts in the Model Policy:

Necessity. For a use of force to qualify as necessary, there should be no other viable alternatives for the officer to achieve the Lawful Objective. If non-force or less aggressive options are available, or if the force does not align with the Lawful Objective, then it is deemed unnecessary. This principle's importance becomes clear when reflecting on instances such as a 2020 incident in Windsor, Virginia, where officers stopped Army lieutenant Caron Nazario for an alleged license plate issue. Despite Lt. Nazario's compliance and evident fear, officers drew their guns and later pepper sprayed him. This kind of event underscores the need for a strict necessity standard, as the force used was not necessary for the officers’ objectives.

Proportionality. Proportionality in force goes beyond necessity. Even if the force is necessary to achieve the Lawful Objective, it must also match the threat posed to the officer or public. An instance highlighting this is a 2020 incident in Loveland, Colorado, where officers arrested Karen Garner, a 73-year-old woman with dementia, for an alleged minor theft. Yet, their response—forcibly restraining and injuring Garner—was clearly disproportionate to her actions and the threat she posed. This instance emphasizes the need for a proportional standard, guiding officers to evaluate and match their response to the situation's true demands.

The Model Policy underscores that necessity and proportionality should be assessed at the time of the incident. What may be necessary and proportionate at the outset of an officer's interaction can quickly become inappropriate as situations evolve. Officers, therefore, must remain vigilant and consistently adjust their evaluations to the changing dynamics of their interactions.

While high-profile incidents of unjustified deadly force often capture widespread attention, it is crucial to recognize the ramifications of the more frequent use of unnecessary and disproportionate non-deadly force. The repeated application of unnecessary non-deadly force erodes community trust[20] and heightens tensions, potentially paving the way for incidents involving more severe, even lethal, force.[21]

The cornerstone to the effective application of the necessity and proportionality standard is comprehensive police training.[22] The Model Policy aims to minimize the use of force and achieving this aim depends on officers becoming proficient in rapidly assessing situations and recognizing the minimum amount of force needed. Without proper training, this standard could lean more towards punishing officers for excessive force rather than serving as a proactive tool for prevention.

Proper training requires changes on both the philosophical and practical levels and goes hand in hand with the training needed to properly implement de-escalation techniques.[23] Philosophically, a department's ethos should reflect an unwavering commitment to human life, pushing officers to approach most public encounters with the belief that they can achieve a resolution without force. Practically, comprehensive training in de-escalation strategies, non-lethal alternatives, and nuanced threat assessment is essential.[24]

Totality of the circumstances: a comprehensive framework to assess situations and threats

The Model Policy directs officers to evaluate the totality of a situation's circumstances to determine a proportional response to potential danger. This comprehensive assessment encompasses several factors: the feasibility of de-escalation tactics, the time available for a person to comply, the person’s physical and mental ability to comply, the presence of bystanders, potential consequences and risks—including escape, and the initial reason for engagement with the person.

A guiding principle behind the use of force is valuing the sanctity and dignity of human life. The aim is to avoid harm to all—be it the individual, bystanders, or police officers. By demanding a thorough assessment of a situation—the totality of the circumstances, officers are encouraged to explore all available options, thus facilitating a decision based on a range of possible actions, striving for the safest and most appropriate one.[25]

Consider a scenario crafted by the Police Executive Research Forum in its Guiding Principles on Use of Force: an individual, seemingly mentally ill and possibly suicidal, wields a knife defensively.[26] As PERF explains, “Officers may call in additional personnel and resources in order to contain the person safely while trying to talk to him, ask him questions about what is going on in his mind, and buy time in order to give the person many opportunities, over an extend-ed period of time if necessary, to calm down, talk to the officers, build trust and rapport, and ultimately to drop the knife.”

Neglecting factors that lower a threat can lead officers to overestimate necessary force levels.[27] By requiring officers to look for alternatives to force and evaluate de-escalation tactics, officers can better gauge the level of a threat posed by particular circumstances, seek effective ways to mitigate it, and, ideally, avoid reaching the point where force is used and injuries may occur.[28]

Some police departments, like Palm Beach County's Sheriff’s Office in Florida, have adopted strategies to assess the totality of circumstances. For instance, after introducing the "Tactical Pause"—which involves “slowing down the police response in certain types of incidents and taking time to carefully evaluate possible actions”[29]—officer-involved shootings in the county notably decreased.[30] Similarly, the Greater Manchester Police in England adopted a decision-making model requiring officers to “think more critically about their response to various types of situations,” leading officers to feel more equipped and safer when handling conflict situations.[31]

Assessing the totality of the circumstances enables officers to gauge the level of force that is necessary—the minimum force needed in a specific situation—and proportionate to the actual threat.[32] Such practices not only safeguard lives but also foster trust with the communities they are sworn to protect.[33] This trust-building process enhances legitimacy, leading to increased public cooperation and compliance with law.[34] When the circumstances do demand force, this approach equips officers with a framework for making decisions that can later be explained to the community, building legitimacy.[35] An officer employing all available de-escalation techniques before resorting to force can more credibly and convincingly argue the action's necessity.[36]

The totality of the circumstances framework also mandates the evaluation of cultural factors in an officer’s decision-making. By understanding diverse communities' needs, officers can adjust their approach and engagement with community members, fostering mutual respect and trust.[37] The implementation of such a framework by the Greater Manchester Police exemplifies this. Following its adoption, public confidence in the police force surged from 45% to 94%.[38]

However, some departments train officers to evaluate the need for force using a different method—escalating continuums of force. These involve matching specific police tactics and weapons to levels of resistance from a person.[39] Many police agencies use a “force matrix” with two components: a “resistance continuum” and a “force continuum”[40] which “tel[l] an officer what force [they] can use” and “when [they] can use it.”[41] As the person’s level of resistance increases, the officer’s permitted level of force correspondingly increases.

While this method does not require evaluating the totality of circumstances, it offers officers set responses for various threat levels.[42] However, this approach does not guarantee the application of minimal force.[43] Continuums may dictate a linear escalation, even when a situation could be diffused with less force. PERF’s research explains that these continuums “suggest that an officer, when considering a situation that may require use of force, should think, ‘If presented with weapon A, respond with weapon B. And if a particular response is ineffective, move up to the next higher response on the continuum.’”[44] This method can overlook vital situational details, like an individual’s physical disability, and encourage the automatic escalation of force as a solution when non- or lesser-force alternatives fail.

Force continuums often misalign with the principles of the Model Policy. They can permit higher force levels without considering all the relevant information available to an officer and the nuances of a particular situation.[45] If initial attempts to control the situation falter, officers might automatically escalate force. Such a rudimentary approach hampers genuine decision-making geared towards de-escalation and, ultimately, preserving human life.[46]

Deadly force: a last resort for officers in lethal situations

The decision to use deadly force carries profound implications. It endangers not only the life of the force’s target but also the lives of officers and the broader public.[47] Beyond the immediate incident, the disproportionate or perceived unjustified use of deadly force can erode community trust in law enforcement.[48] Thus, deadly force should only be utilized as an absolute last resort.

The Model Policy restricts the use of deadly force to a narrow set of circumstances detailed in this module. Even when those circumstances exist, however, deadly force should only be deployed when it is absolutely necessary and not merely when it is permitted.[49] Many police departments, including those in Dallas and San Francisco, advocate this restrictive approach, emphasizing the use of deadly force as a last resort when all available alternatives have been explored.[50]

This is both a practical and philosophical policy directive. Practically, it discourages haste in employing lethal force, except in dire situations, such as imminent threats of death or grave injury. Philosophically, it underlines that deadly force should be reserved for the most extreme circumstances.

Once all other available options are exhausted, deadly force is authorized in a narrow set of circumstances. First, it can be used to defend an officer or another person from an imminent threat of death or serious bodily harm that is more likely than not to occur without the use of deadly force. This authorized use is consistent with PERF’s Guiding Principles and policy guidance from the International Association of Chiefs of Police, echoing policies already in place in many police departments across the country.[51] The “more likely than not” criterion underscores the requirement of proportionality.

Second, an officer is authorized to employ deadly force during an arrest if there is probable cause to believe the suspect committed a felony that caused or threatened to cause death or serious bodily harm and who the officer believes is more likely than not to cause death or serious bodily harm to an officer or another person unless immediately apprehended.[52] For instance, an officer is authorized to use deadly force against someone seen shooting another person if that individual then attacks the officer or another person.

Yet, past criminal convictions should not form the basis for deploying deadly force. Using force based solely on past crimes would be disproportionate. Even when officers have rightly identified a suspect, the principle of valuing all human life dictates that deadly force should be reserved for those presenting immediate threats, irrespective of past actions.

In any case where deadly force is used, officers must be able to explain the circumstances that led them to believe the use of deadly force was necessary based on the information they had. Facts discovered after the incident cannot retrospectively justify the use of force.

The Policy

1.1 – Key Concepts and Definitions

A. Key Concepts:

- The Department places the sanctity and dignity of human life at the center of this Policy. All officers must avoid the use of force unless it is not possible to do so. Force may be used only after all available non-force options have been exhausted.

- Officers must seek to avoid the use of force unless it is not possible to do so. Any force used must be the least amount of force necessary to achieve a Lawful Objective and proportional to the totality of the circumstances.

- Officers are required to attempt de-escalation techniques to avoid or reduce threats, gain the voluntary compliance of persons, and safely resolve a situation before resorting to force.

- Deadly force is a last resort and may only be used by officers when all other force options have been exhausted and it is absolutely necessary to protect the officer or another person from death or serious injury.

B. Definitions:

-

Available Information: The information that was obtainable or accessible to an officer at the time of the officer’s decision to use force. When an officer takes actions that hasten the need for force, the officer limits their ability to gather information that can lead to more accurate risk assessments, the consideration of a range of appropriate tactical options, and actions that can minimize or avoid the use of force altogether.

-

De-Escalation: Taking action or communicating verbally or nonverbally during a potential force encounter in an attempt to stabilize the situation and reduce the immediacy of the threat so that more time, options, and resources can be called upon to resolve the situation without the use of force or with a reduction in the level of force necessary.

-

Lawful Objective: Limited to one or more of the following objectives:

a) Conducting a lawful search;

b) Preventing serious damage to property;

c) Effecting a lawful arrest or detention;

d) Gaining control of a combative individual;

e) Preventing and/or terminating the commission of a crime;

f) Intervening in a suicide or self-inflicted injury; and/or

g) Defending an officer or another person from the physical acts of another.

-

Necessary: Force is necessary only if there are no other available non-force options or less-forceful options to achieve a lawful objective.

-

Proportional: Proportionality in the use of force goes beyond necessity. Even if the use of force is necessary to achieve the Lawful oObjective, it must also match the threat posed to the officer or public.

-

Totality of Circumstances: The totality of the circumstances consists of all facts and circumstances surrounding any event.

1.2 – Authorization Required to Use Force

A. Authorization to Use Force

The use of force is authorized only when all the following circumstances exist:

- There is a Lawful Objective;

- The officer has exhausted all available non-force options to apprehend or control the person;

- The officer issues a verbal warning before using force, if possible;

- The use of force is necessary to carry out the Lawful Objective and proportional to the totality of the circumstances; and

- The amount of force is limited to the minimum amount of force the officer believes is feasible to carry out the Lawful Objective and will not injure bystanders, and those beliefs are consistent with Available Information.

B. De-Escalation Required Before Using Force

De-Escalation techniques are tools of first resort. Officers must use the available De-Escalation techniques and tactics in this policy before resorting to force, in an attempt to stop or reduce a threat without the use of force.

C. Factors to Consider before Using Force

Before using force an officer should assess how to safely resolve the situation. The following factors should be considered by officers:

- Seriousness and nature of the alleged offense and level of perceived threat from the person, including the level of resistance exhibited by person;

- Non-force and force options available to the officer; and

- Person’s perceived personal characteristics including behavioral disorders, physical disabilities, language abilities, and cultural background.

1.3 – Authorization Required to Use Deadly Force

A. Authorization to Use Deadly Force

The use of deadly force is authorized only when all the requirements to use force are satisfied and both of the following additional circumstances exist:

-

All available non-deadly force options have been exhausted; and

-

The use of deadly force is absolutely necessary:

- To protect an officer or another person from imminent death or serious bodily harm that is more likely than not to occur without the use of deadly force, provided that the officer can specifically articulate the observable circumstances that led the officer to conclude that the use of deadly force is necessary, and the officer’s belief is consistent with Available Information; or

- To effect the arrest of an individual who the officer has probable cause to believe has committed a felony that caused or threatened to cause death or serious bodily harm; and the officer believes that the individual is more likely than not to cause death or serious bodily harm to an officer or another person unless immediately apprehended and the officer’s belief is consistent with Available Information.

B. Deadly Force Prohibited

Regardless of whether the circumstances in this policy above are satisfied, deadly force may not be used against any of the following three categories of individuals:

- Individuals who pose a threat only to themselves;

- Individuals suspected of committing a misdemeanor or non-violent felony, unless the use of deadly force is necessary to protect an officer or another person from imminent death or serious bodily harm, the officer can specifically articulate the observable circumstances that led the officer to conclude that the use of deadly force is necessary, and the officer’s belief is consistent with Available Information; or

- Fleeing individuals, unless the use of deadly force is necessary to protect an officer or another person from imminent death or serious bodily harm, the officer can specifically articulate the observable circumstances that led the officer to conclude that the use of deadly force is necessary, and the officer’s belief is consistent with Available Information.

C. Avoiding Conduct that Increases Risk of Deadly Confrontation

Officers must be aware that they can escalate situations to where they feel that deadly force is necessary. An officer’s conduct before a confrontation must not increase the risk of a deadly confrontation. The Department will consider the following factors in determining whether an officer’s conduct increased the risk of a deadly confrontation:

- Whether the officer missed opportunities to de-escalate;

- Whether the presence of officers escalated what was initially a minor/non-threatening situation and eliminated the opportunity for de-escalation; and

- Whether the officer genuinely and reasonably believed deadly force was necessary given the officer’s conduct before the confrontation.

1.4 Standard for Using Force

A. Standard for Use of Force

The amount and type of force used must be necessary to carry out a Lawful Objective and proportional to the totality of the circumstances.

B. Necessity Requirement

For force to be necessary:

- The amount and type of force used must be for carrying out the Lawful Objective;

- There must be no available non-force options to carrying out the Lawful Objective given the circumstances, or the options have been exhausted, and

- There must be no available lesser-force options to carrying out the Lawful Objective given the circumstances, or the options have been exhausted.

C. Proportionality Requirement

Officers are required to assess the totality of the circumstances of a given situation to determine what response is proportional to the potential danger posed by the person. Force is proportionate when the force used corresponds in amount or degree with the Lawful Objective or with the threat posed to the officer or public.

D. Measuring Necessity and Proportionality of Force

The necessity and proportionality of the force shall be measured at the time force is applied. Force that may have been necessary and proportionate at one time during the officer’s encounter with a person may not be necessary or proportionate if used later in the encounter.

E. Excessive Force is Prohibited

An officer may not use more force than necessary in a particular situation after evaluating the totality of the circumstances.

Endnotes

- Graham v. Connor, 490 U.S. 386, 395 (1989).

- Id. at 396.

- Id. at 397 (“[T]he ‘reasonableness’ inquiry in an excessive force case is an objective one: the question is whether the officers’ actions are ‘objectively reasonable’ in light of the facts and circumstances confronting them, without regard to their underlying intent or motivation.”).

- See, e.g., Villegas v. City of Anaheim, 998 F. Supp. 2d 903, 905-08 (C.D. Cal. 2014) (granting summary judgment to police officers who shot and killed a civilian based on their mistaken belief he was armed with a shotgun—which was actually a BB gun—without any consideration of the officers' training, expertise, and experience regarding the identification and characteristics of firearms), aff'd in part, rev'd in part, and remanded by & through C.V. v. City of Anaheim, 823 F.3d 1252 (9th Cir. 2016).

- Kelly M. Hogue, "When an Officer Kills: Turning Legal Police Conduct into Illegal Police Misconduct," 98 Texas Law Review 601, 609 (Feb. 2020).

- The Buffalo News asked lawyers and experts for their take on the question and got varied answers. Most jurors who sit through a trial come away with the realization that “police work involves force,” and officers are trained and authorized to use it at times. See generally, Debra Cassens Weiss, “Why do juries acquit police officers of brutality? Experts offer differing explanations," (March 15, 2019).

- See, e.g., City & County of San Francisco v. Sheehan, 135 S. Ct. 1765 (2015); Cynthia Lee, "Reforming the Law on Police Use of Deadly Force: De-Escalation, Pre-Seizure Conduct, and Imperfect Self-Defense," 2018 U. Ill. L. Rev. 645.

- See e.g., Donovan Corson Kelley, "Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Police Officer Acquittals: Jurors' Explicit and Implicit Racism," Doctoral Dissertations 2576 (2021), (jurors high in explicit racism were more likely to acquit police officers of murder than jurors low in explicit racism).

- Lee, supra note 7, at 645–46.

- Celia Feldman, "Is “Objective Reasonableness” Really Objective? Examining the Shortcomings of Police Use of Force Evaluations," University of Baltimore Law Review Online (Oct. 30, 2020), see also Lee, supra note 7, at 645–46.

- Hogue, supra note 5, at 601; Jose A. Del Real, "No Charges in Sacramento Police Shooting of Stephon Clark," New York Times (Mar. 2, 2019).

- See Mitch Zamoff, "Determining the Perspective of A Reasonable Police Officer: An Evidence-Based Proposal," 65 Villanova Law Review 585, 588 (2020) (stating that the U.S. Supreme Court has held that the reasonableness of police officer conduct at issue in an excessive force lawsuit should be evaluated from the perspective of a “reasonable officer on the scene” rather than the “reasonable person” perspective typically used to determine liability in situations involving alleged tortious conduct); Hailey Fuchs, "Qualified Immunity Protection for Police Emerges as Flash Point Amid Protests," New York Times (June 23, 2020), (discussing systemic racism in policing and use of excessive force); Devon W. Carbado & Patrick Rock, "What Exposes African Americans to Police Violence?," 51 Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review 159, 175-85 (2016) (summarizing the different types of social and psychological threats police officers might feel, which increase the likelihood of officer violence); Song Richardson & Phillip Atiba Goff, "Interrogating Racial Violence," 12 Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law 115, 128-42 (2014) (research from social psychology suggests that officers who use a disproportionately large amount of force against African American men might be trying to assert their manhood even more than their authority).

- Jelani Jefferson Exum, "Nearsighted and Colorblind: The Perspective Problems of Police Deadly Force Cases," 65 Cleveland State Law Review 496 (2017); Zamoff, supra note 12, at 599 (The Graham Court did not provide any guidance regarding what characteristics of reasonable police officers should be taken into account in assessing the reasonableness of their use of force under Section 1983 other than to caution the lower courts to allow for the fact that “police officers are often forced to make split-second judgments--in circumstances that are tense, uncertain, and rapidly evolving--about the amount of force that is necessary in a particular situation). Moreover, federal courts often referenced, relied upon, or deferred to the meaning of excessive force created by police departments in their use of force documents. Such deference explains, in part, why courts frequently do not hold police officers accountable for excessive force against citizens. By ceding to police understandings of excessive force in defining the scope of Fourth Amendment protections, federal courts essentially allow police to make constitutional rules for themselves—the endogenous Fourth Amendment. See generally Osagie K. Obasogie & Zachary Newman, "Constitutional Interpretation Without Judges: Police Violence, Excessive Force, and Remaking the Fourth Amendment," 105 Virginia Law Review 425, 427 (2019). Without any definitive judicial guidance on what evidence may be considered in determining how a reasonable officer on the scene of an excessive-force incident would have behaved, courts have issued ad hoc, inconsistent decisions that are often difficult to reconcile with basic evidentiary principles. See generally, Zamoff, supra note 40.

- Lee, supra note 7, at 645.

- Hogue, supra note 5, at 613–14.

- Peace officers: deadly force, A.B. 392 (Cal. 2019).

- See, e.g., Los Angeles, Arlington, Madison, Newark.

- The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, "New Era of Public Safety: A Guide to Fair, Safe, and Effective Community Policing," 127 (2019).

- 19 See, e.g., Police Executive Research Forum (“PERF”), "Guiding Principles on Use of Force" 36 (Mar. 2016); Nashville § 11.10.010; Philadelphia Police Dep’t Directive 10.1(3)(A); San Francisco Police Dep’t Gen. Ords. § 5.01(III)(B).

- People call 911 less often after high-profile instances of police brutality. See, e.g., Matthew Desmond, Police Violence and Citizen Crime Reporting in the Black Community, ASA 1,1-20, (Sept. 2016).

- The idea that a show of force will deter criminal activity or unruly activity is not always supported by evidence. See, e.g., "New Directions in Protest Policing," 35 SLU L. Rev. 67, 67-108 (2015) (researchers have spent 50 years studying what happens when the police respond by escalating force—it does not often work).

- Even when not advocating for a general necessary and proportionate standard, police organizations recognize that this kind of training is essential to lessening incidences of use of force. See, e.g., International Association of Chiefs of Police, "National Consensus Policy and Discussion Paper on Use of Force," § IV.E (July 2020).

- A first step in the effective and formal deployment of de-escalation is to ensure it has a top-down organizational commitment from all the stakeholders. De-escalation training should begin in the police academy and continue consistently throughout officers’ careers. Further, it should be taught not as a standalone topic, but instead as a norm in policing culture, with pertinent skill sets woven as a common thread throughout education and training. See, e.g., California Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training, "De-Escalation Strategies & Techniques for California Law Enforcement," (2020).

- See id.

- PERF, Guiding Principles, supra note 19, at 20.

- Id.

- New Era, supra note 18, at 121.

- PERF, Guiding Principles, supra note 19, at 21.

- Id. at 86.

- Id. at 55.

- Id. at 28.

- Id. at 20. It is worth noting that while the process of assessing the totality of the circumstances may seem complicated, officers who have used critical decision-making models requiring them to undergo a similar analysis, noted that “they quickly became accustomed to using it every day for making decisions about all types of situations” and that the “model becomes second natured to them.” Id. at 28.

- Id. at 30.

- Final Report of The President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing, 10.

- PERF, Guiding Principles, supra note 19, at 86, 87 (noting that the “experience in the UK has demonstrated that [critical decision-making] can be quite valuable in helping officers describe and explain their actions” and that officers routinely use this in describing their actions and decisions).

- Lee, supra note 7, at 629, 670.

- New Era, supra note 18, at 141.

- PERF, Guiding Principles, supra note 19, at 27.

- Id. at 19.

- Brandon Garrett & Seth Stoughton, "A Tactical Fourth Amendment," 103 Virginia Law Review 211, 269 (2017).

- Id. at 211, 270.

- Id. at 211, 272.

- Id. at 211, 274.

- PERF, Guiding Principles, supra note 19, at 19.

- Garrett & Stoughton, supra note 40, at 211, 274.

- DLG Learning Center, "Use of Force Continuum – Seriously?? What is old is now new and what is new is clearly broken…” (June 2020).

- See, e.g., Easterling v. City of Glennville, 694 F. Supp. 911, 922 (S.D. Ga. 1986) (in a Section 1983 case against officers whose police chase resulted in the subject’s car leaving the road, striking a tree, causing the subject’s death, noting that “the defendant officers may have been negligent and/or reckless in failing to break-off the chase and arrest [the driver] at a later time when it would have been safer for all concerned”) (emphasis added).

- Principles of the Law, Policing § 13.08 TD No 3 (2021) ( “significant individual events may undermine community trust and reveal avoidable obstacles to sound policing.”); see also e.g., Monica C. Bell, "Police Reform and the Dismantling of Legal Estrangement," 126 Yale Law Journal 2054 (2017) (“many scholars and policymakers diagnose the frayed relationship between police forces and the communities they serve as a problem of illegitimacy, or the idea that people lack confidence in the police and thus are unlikely to comply or cooperate with them.”).

- Id.

- See, e.g., San Francisco Police Dep’t, Gen. Ord. 5.01: Use of Force Policy 1-2, 5-6, 15 (Dec. 21, 2016); Dallas Police Dep’t Gen. Ords. § 906.01(C); San Francisco; see also Austin Police Dep’t Pol’y Manual at 6; Denver Police Dep’t Operations Manual § 105.01(1)(a); Los Angeles Police Dep’t Pol’y on the Use of Force § I; Sacramento Police Dep’t Gen. Ords. § 580.02(K)(1); PERF, Guiding Principles, supra note 19.

- See PERF, Guiding Principles, supra note 19, at 22; International Association of Chiefs of Police, National Consensus Policy and Discussion Paper on Use of Force 3–4 (July 2017); see also Minneapolis § 5-301(III)(B), Nashville §§ 11.10.120–130; Stockton § IV.A.12–14; Omaha §§ III–IV.

- Id.