Duties to Intervene, Provide Medical Aid, and Safely Transport

Clear and comprehensive policies on intervening in misconduct, providing medical aid, and safely transporting detainees can protect officers and community members while providing important transparency and accountability.

- Introduction

- Key things to know

- Understanding Policies on Intervening in Misconduct, Providing Medical Aid, and Safely Transporting Detainees

- The Policy

- Endnotes

Introduction

Intervening in misconduct and providing aid: Why are policies codifying these duties important for police and the communities they serve?

Police officers carry a complex set of responsibilities—ensuring public safety while building public trust in the integrity of their profession and the legitimacy of law enforcement actions. Two crucial duties lie at the heart of these responsibilities: the duty to intervene when they observe fellow officers using unnecessary force or unlawful policing practices, and the duty to provide immediate medical aid following a use of force.

Officers should be required to intervene in the face of potential misconduct within their ranks. Our research reveals that this important duty extends beyond merely enforcing the law—it's about safeguarding the integrity of the police institution and fostering a culture of accountability. Following a use of force, officers also bear a critical duty to provide medical aid. The moments immediately after a use of force incident can have a significant impact on the outcome for those involved, shaping perceptions of the incident and influencing the level of trust between law enforcement and the community. As this module explains, both the duties to intervene and to provide medical aid serve as powerful reminders that the mission of the police should be broader than upholding laws—it should be rooted in preserving life, respecting human dignity, and nurturing the community’s trust and confidence in police work.

Downloads

Policy on Duty to Intervene and Provide Medical Aid

Download the model policy on the Duty to Intervene and Provide Medical Aid.

Download PolicyFull Model Use of Force Policy

Download the Full Model Use of Force Policy – 10 detailed policies designed to help communities implement more effective use of force policies that enhance community safety while minimizing unnecessary force.

Open Full Model Use of Force PolicyKey things to know

- When an officer is aware of another officer’s misconduct or has reason to believe the other officer is about to engage in misconduct, the officer must intervene to stop or prevent the misconduct.

- The duty to intervene is ongoing and continues until another officer’s misconduct ends. The officer aware of misconduct—including excessive force, tampering with evidence, bias-based profiling, or harassment—must also report the matter, within 24 hours, to their supervisor following the department’s reporting procedures.

- An officer who fails to intervene or report misconduct is subject to discipline. Retaliation against an intervening or reporting officer is prohibited.

- An officer must immediately provide medical aid, to the best of their ability and training, whenever officers have used force on a person and there is an injury, a claim of injury, a request for medical attention, physical or mental distress, or difficulty breathing.

- An officer’s duty to provide aid includes immediately summoning emergency medical services to the scene.

Understanding Policies on Intervening in Misconduct, Providing Medical Aid, and Safely Transporting Detainees

While situations involving non-compliant people present officers with choices about using force, they often present officers with another set of inflection points where the consequences of the decisions facing the police can be so significant that the decision-making should not be left to an individual officer’s discretion. These decision points include whether an officer who witnesses their colleagues use excessive force, or commit another type of misconduct, should intervene to end the inappropriate—and likely unlawful—behavior. Once force has been used, an officer can be confronted with the question of whether they should step in and assist a person that, perhaps seconds before, had been combative and unwilling to comply with their orders. Police departments have recognized the challenges posed by these circumstances and have increasingly required their officers to act in a manner that protects community members and strengthens perceptions of the police’s legitimacy.

A review of more than 100 police department policies from agencies across the U.S. reveals that most agencies now require their officers to intervene in misconduct and provide medical aid. It is promising that, in recent years, many departments have added written policies reaffirming these duties for their officers. The Model Policy builds upon this progress and recommends specific and robust policies that: eliminate ambiguities, help officers understand what is expected of them when confronted with these situations, and formalize the expectation that misconduct and deviation from a department’s policies will not be tolerated.

The critical role officers play in holding—or not holding—their fellow officers accountable

Police officers play a critical role in holding—or not holding—their fellow officers accountable for excessive uses of force. Incidents across the U.S. illustrate how police that observe other officers crossing the line and choose to intervene are protecting community members from harm, and even saving lives, by stepping in before situations escalate further. On the other hand, officers that do not respond to their colleagues’ unlawful uses of force are contributing to the harm created by their fellow officers and, in some cases, the deaths of people at the hands of police.

In 2015, a McKinney, Texas police officer, Corporal Eric Casebolt, responded to a reported disturbance at a community pool.[1] Video from the incident shows Casebolt yelling and chasing youths, shoving one boy to the ground, before dragging Dajerria Becton, a 15-year-old Black girl, across the ground while fellow officers stood nearby. When two unarmed Black teens attempted to come to Becton’s aid, Casebolt unholstered his firearm and drew it towards the two teens. Upon seeing Casebolt draw his gun, two fellow officers rushed to his side, intervening as the teens fled, and Casebolt returned his weapon to his holster. Had those two officers not stepped in—albeit after observing their colleague’s escalating behavior—the two teen boys might have been shot and killed by Casebolt.

Officers in Baltimore and Memphis did not intervene as their colleagues violated department policies and used excessive force against Freddie Gray, Jr. and Tyre Nichols, killing both Black men. Gray died a week after four Baltimore Police Department officers did not act when he screamed in pain as two of their fellow officers held him face-down on the sidewalk with his legs bent “‘like he was a crab or a piece of origami.’”[2] After arresting Gray, one of the officers transported him to a local trauma care facility, but not without knowingly neglecting to secure Gray with a seatbelt and purposefully driving erratically to further injure him.[3] Gray arrived at the local trauma care facility unresponsive and later died there after sustaining injuries to his voice box, three fractured vertebrae, and a spinal injury severing 80% of his neck.[4]

As Memphis Police Department officers kicked, punched, and pepper sprayed Tyre Nichols, several of their colleagues stood nearby and did not move to stop the officers using unnecessary force. Then, after handcuffing one of Nichols’ wrists, an officer struck him with a baton multiple times, again triggering no intervention from the several officers that were surrounding Nichols. Once Nichols was subdued, officers with medical training waited 16 minutes to provide him with aid. Like Gray, days later Nichols died of his injuries.

In the New York City borough of Staten Island, nearly a dozen officers of the New York Police Department were on scene as Officer Daniel Pantaleo violated their department’s ban on chokeholds in restraining Eric Garner, who repeatedly pleaded for his life muttering, “I can’t breathe.”[5] Garner’s plea was unsuccessful in eliciting an intervention from the NYPD officers and continued to be unsuccessful six years after his death when George Floyd uttered “I can’t breathe,” multiple times as three Minneapolis Police Department officers did not act as one of their colleagues, Derek Chauvin, held Floyd to the ground with a knee to his throat for nearly nine minutes.[6]

The deaths of these Black men—Freddie Gray, Tyre Nichols, Eric Garner, and George Floyd—did not have to occur and could have been avoided if the officers on-scene had intervened to stop the excessive force, provide needed medical aid, and, in the case of Gray, safely transport a detainee. Ending these types of incidents that threaten and take human life should be sufficient motivation for police departments and cities across the U.S. to evaluate and improve their policies. But the failure of an officer to intervene when witnessing excessive force can also be grounds for an officer, the department, and the city to be held liable under federal civil rights law 42 U.S.C. § 1983.[7]

Requiring officers to intervene and stop misconduct

Though officers arguably have a legal duty to intervene in cases of excessive force, regardless of whether a department adopts a specific policy requiring intervention, there are several ways departments can enact clear policies that benefit their officers and they communities they serve. The Model Policy recommends an approach that, instead of limiting the explanation of the duty to a sentence or paragraph, provides a more thorough description that helps clarify expectations of police officers and eliminate ambiguity to the extent possible.[8]

At its core, the policy establishes the duty for an officer who witnesses another officer engage in misconduct, or who has reason to believe that another officer is engaged in or about to engage in misconduct, to intervene to end or prevent the misconduct. This duty should apply to every officer, regardless of rank, seniority, or title. It should also continue until the misconduct ends.

A robust duty to intervene policy should define at least two crucial terms: (1) intervention and (2) misconduct. “Intervention” should include both verbal and physical measures and the policy should explain that the duty may be triggered prior to officers witnessing misconduct. Even when an officer only has reason to believe that another officer is about to engage in misconduct (e.g., witnessing another officer become agitated with respect to a person, or hearing from an officer that a third officer is becoming “heated” with respect to a person), the duty should be triggered.

In defining “misconduct” the policy should take a broad view of the types of actions that trigger the duty. Specifically, the policy should not limit the duty to situations involving excessive force, but should instead cover any violation by an officer of the department’s policies, of state and/or federal criminal law, or of the state’s constitution or the U.S. Constitution. Such a policy would still require officers to intervene to prevent or stop the use of excessive force, but would also require intervention to prevent or stop, for example, instances of misrepresentation, evidence planting or tampering, bias-based profiling, harassment, or the use of racial epithets or slurs.

To help officers grasp and visualize an effective intervention, the Model Policy recommends explaining and providing examples of both verbal and physical interventions, as well as highlighting when the two types of intervention would be most appropriate.[9] A policy should explain that verbal interventions are usually preventative measures used when an officer suspects another officer is on the path toward engaging in misconduct, and should caution that verbal interventions may be insufficient to satisfy an officer’s duty to intervene when actual misconduct is occurring. Conversely, the policy should explain that physical interventions should be used when verbal interventions have not worked or seem unlikely to work, and explicitly note that physical interventions include both putting one’s body between an officer and the victim of misconduct, as well as forcibly restraining or removing an officer committing or attempting to commit misconduct.

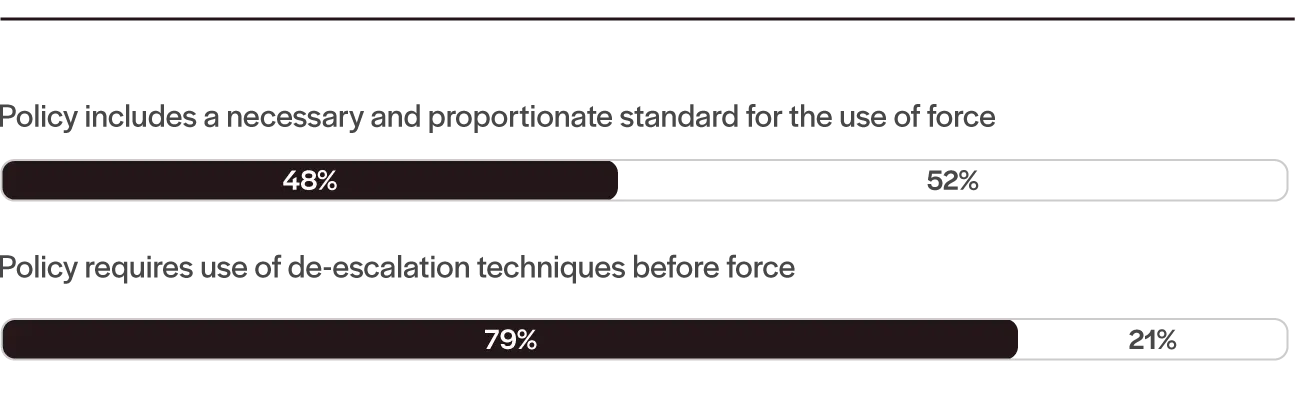

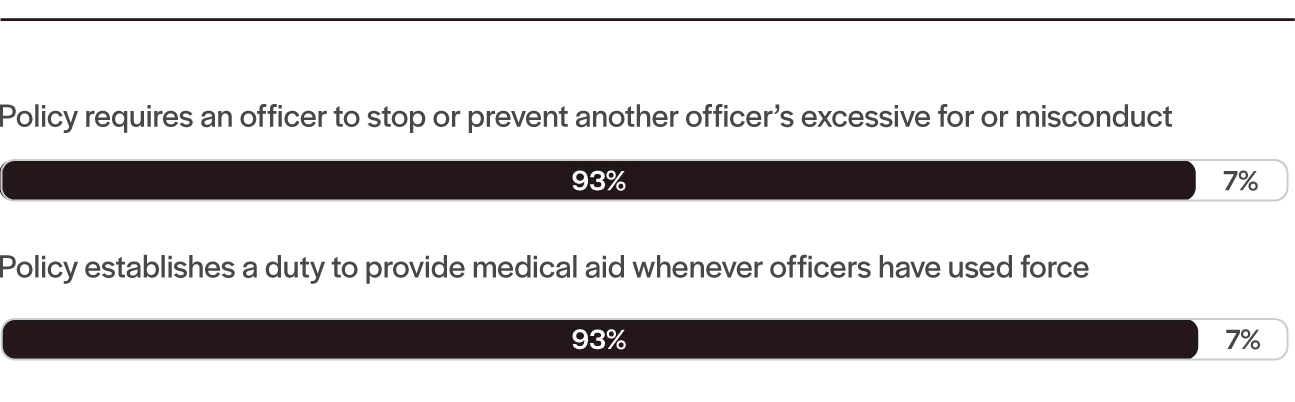

Key Force Regulations in Policies of 100 Largest U.S. Cities

Intervention and Aid Regulations in Policies of 100 Largest U.S. Cities

Disciplining officers that do not fulfill their duties

When officers do not fulfill their duty to intervene, they jeopardize the safety of community members and threaten the community’s trust in the police. For these reasons, there must be consequences for officers that observe misconduct and do not act to end it.[10] The Model Policy includes a provision specifying that the failure either to intervene to prevent/stop misconduct, or to report such misconduct, will be grounds for disciplinary action at the same level of severity as the original act of misconduct.[11]

Prohibiting retaliation against intervening officers

A duty to intervene will not be effective unless it protects officers who comply with the duty from retaliation.[12] The Model Policy suggests specifying that officers are immune from retaliation, reassignment, or any other disciplinary action as a result of preventing, stopping, or reporting the misconduct or attempted misconduct of another officer. To reinforce the requirement that the duty to intervene applies even where the intervening officer is outranked by the offending officer, the anti-retaliation clause also should specify that intervening and reporting cannot be a basis for any disciplinary action for insubordination.

Requiring officers to provide and obtain medical aid

When police use force against a person, they increase the likelihood the person will be injured and need medical care. Officers on scene are the first responders following a use of force and, as first responders, they are the best positioned to provide prompt medical aid until emergency medical services (“EMS”) arrive. Because the Model Policy prioritizes the sanctity of life, it imposes a duty for officers to immediately provide medical aid, to the best of their skill and ability, until EMS personnel are on scene.

Despite a growing consensus on requiring officers to provide medical aid following the use of force, many police departments have come under scrutiny for officers’ failure to administer aid in such circumstances, even when officers summoned EMS. In Rochester, New York in 2020, officers restrained Daniel Prude by placing a spit hood on his head and forcibly pushing his face into the asphalt.[13] While restraining Prude, the officers noticed him vomiting. Rather than provide medical assistance, the officers continued to restrain him for three minutes and ten seconds before EMS arrived to perform chest compressions on an unresponsive Prude. Prude was taken to a hospital, where he was declared brain dead and subsequently died a week later as a result of complications of asphyxia.

There are troubling examples of delayed or withheld medical aid involving departments around the U.S. In Tulsa, Oklahoma in 2016, officers waited over two minutes to begin first aid on Terence Crutcher, whom they had shot, and he later died from his wounds.[14] In Charlotte, North Carolina in 2019, officers shot Danquirs Franklin and then did not attempt to provide first aid. Four minutes passed before EMS arrived to treat Mr. Franklin, who died of his injuries.[15]

Medical professionals have found that delaying care, even for minutes, substantially increases the risk of death or severe disability following a traumatic event.[16] Even though EMS may arrive on the scene within minutes, the delay may have a profound impact on an individual’s prognosis. Nonetheless, police officers have no common law duty to provide medical aid.[17] Departments must use their administrative policies to establish this duty and, in doing so, should consider several key policy areas.

Defining “medical aid” is critical and departments have adopted different views of the concept. Some department policies simply state that medical aid must be given but do not offer more specific instructions. Many departments consider the duty to render aid fulfilled when officers call for EMS, but do not require officers to give first aid themselves. Other departments require, or explicitly permit, officers to provide aid in addition to calling for EMS. Finally, some departments go one step further and detail instances where EMS must be called regardless of an individual’s apparent injury. These include when certain weapons, such as pepper spray, are used; when the individual at issue falls into certain categories such as pregnant or elderly; or when someone has been struck in the head. Additionally, departments differ on whether they require the immediate provision of aid, with some departments not mentioning a timeframe at all.[18]

As the cases from Rochester, Tulsa, and Charlotte suggest, waiting to provide aid, or merely calling for EMS, does not suffice to protect human life or ensure public trust in police. For these reasons, the Model Policy requires that officers immediately call for EMS and immediately administer first aid until EMS arrives following the use of force against any person injured, claiming injury, requesting medical attention, exhibiting physical or mental distress, having difficulty breathing, who was struck in the head, who falls into certain high-risk categories, or when officers use certain weapons.

Additionally, the Model Policy, following many policies across the U.S., requires officers to continuously monitor individuals impacted by the use of force until EMS takes over care. Officers may not immediately perceive a person’s injuries, or the injuries may worsen over time, rendering an initial, point-in-time evaluation inadequate to sufficiently care for the person. Even though officers should not place or restrain an individual in a way that restricts their airway in the first place, officers should continue to check that restrained individuals are able to freely breathe.

The Model Policy prioritizes the preservation of human life, however it will only be successful if officers are equipped to provide life-saving care. Because improper medical care can do more harm than good, police departments must provide officers with proper and ongoing training. But full emergency medical technician training is not required. The skills needed to provide life-saving care while awaiting EMS are not overly complicated to learn or execute.[19] More police departments around the country now offer the appropriate training and require their officers to complete it.[20]

Departments should also provide their officers with the necessary tools to administer first aid. This too is becoming more commonplace, with many departments outfitting every police vehicle—and in some departments every officer—with a trauma kit.[21]

Reporting misconduct and documenting medical aid

It is crucial for officers to promptly report misconduct. The Model Policy creates such a duty and specifies precisely when the intervening officer must report the misconduct, rather than utilizing an open-ended variation of “as soon as practicable” or “with reasonable promptness.”[22] The reporting requirement should list any mandatory details that must be included in a report, such as the who, what, when, where, and how regarding the misconduct, information about other officers who were present when the misconduct occurred, and any actions other officers took or failed to take in response to the misconduct. Furthermore, the reporting requirement should impose an affirmative duty on supervising officers to both investigate reports of misconduct and pursue disciplinary action against officers found to have committed misconduct.

The Model Policy also requires officers to document any medical aid provided following the use of force, including describing injuries sustained, how those injuries were caused, and the nature of the aid administered—or the individual’s refusal of aid.[23] This documentation protects police officers and departments, especially in instances where an individual refuses medical care, as is their right. Additionally, a requirement to document reinforces for officers that medical aid is an essential and required part of their job.[24]

Duty to safely transport

Recognizing the value of human life, the Model Policy includes a duty for officers to safely transport all persons within their care. It outlines the risks associated with certain positions and restraints, particularly the dangers of positional asphyxia, which can result from commonly used techniques such as "hog tie" restraints and "hobble" restraints. To mitigate these risks, the policy expressly prohibits the use of specific restraints and positions, with handcuffs identified as the preferred restraint device for transportation. Officers are mandated to avoid any position that risks positional asphyxia and to ensure that individuals are safely secured in an upright position within the vehicle. Furthermore, additional factors like the person’s mental condition, the potential presence of stimulants, and other physical aspects are considered as contributing elements that officers must be trained to recognize and handle with caution.

The policy also emphasizes the need for extensive training and authorization processes for officers, especially concerning positional asphyxia and the use of specific restraints or techniques. This includes a mandate for certification, compliance with updated training programs, and a requirement that only trained officers are authorized to use particular restraint methods. Moreover, the policy prescribes specific provisions on the use of "hobble" and other leg restraints, emphasizing that their use must be both necessary and proportionate to either the risks to the officer or the need to protect the person from their own actions. Detailed guidance on evaluating mental conditions and potential risk factors, along with policies addressing documentation and reporting measures—like video and audio recordings during transportation—further underscore the comprehensive nature of the Model Policy’s approach.

The Policy

1.1 – Key Concepts and Definitions

A. Key Concepts:

- Officers have legal and moral obligations to the public they serve. Requiring officers to intervene and prevent or stop another officer from committing misconduct increases the Department’s legitimacy, enhances public safety, and builds public trust in the police.

- Preserving human life is this Department’s highest priority. Ensuring that persons who require medical attention receive immediate medical aid following a use of force is essential to upholding this priority.

- Officers must ensure the safe transportation of all persons within their care.

B. Definitions:

- Intervene: To come between an officer and another person, through either physical or verbal means, to prevent misconduct from taking place or to end misconduct that is already taking place.

- Misconduct: Any act or failure to act that violates an officer’s oath of office; Department policies or procedures; the laws of [State] or the United States; or the [State] Constitution or the United States Constitution. This includes, but is not limited to, acts of excessive, unauthorized, or unnecessary force; or acts of force that began as authorized and necessary but became unauthorized or unnecessary as the circumstances developed or changed.

1.2 – Duty to Intervene

A. Duty to Intervene

- If an officer witnesses another officer engage in misconduct or has reason to believe that another officer is engaged or about to engage in misconduct, that officer must intervene to end or prevent the misconduct. This expressly includes when the officer observes another officer’s acts of force that began as authorized and necessary, but subsequently become unauthorized or unnecessary as the circumstances developed or changed.

- This duty to intervene commences as soon as the officer has reason to believe that misconduct by another officer is likely to occur or the officer witnesses the misconduct occurring, whichever occurs first. This duty continues unless and until the conduct in question has completely stopped.

- This duty to intervene applies regardless of the officer’s tenure, rank, or seniority.

B. Types of Intervention

- Verbal intervention: Verbal interventions should be used to prevent misconduct when an officer has reason to believe that another officer may be about to engage in misconduct. Examples include asking an agitated officer a question to redirect their attention, asking a question to the person with whom the agitated officer is engaged to give the officer a chance to collect themselves, and asking an agitated officer to talk with you away from the person with whom the officer is engaged. Verbal interventions may be insufficient to stop misconduct that is already taking place.

- Physical intervention: Physical interventions should be used to stop misconduct that is already occurring and may be necessary to prevent misconduct if verbal interventions do not appear to be working. Physical interventions include putting one’s body in between an officer and a person, using one’s body to protect the individual against whom misconduct is occurring, or forcibly restraining or removing an officer from a situation in which the officer is engaging in misconduct.

C. Duty to Report Misconduct

- Requirement to Report Misconduct. If an officer observes another officer commit or attempt to commit misconduct or has a good faith reasonable belief that another officer committed or attempted to commit misconduct, that officer must report, within 24 hours, such wrongdoing to a supervisor in accordance with the Department’s reporting policies and procedures.

- Protection from Retaliation. No officer who intervenes in or reports misconduct under this policy will be subject to retaliation, reassignment, or any other disciplinary action for taking such actions.

1.3 – Duty to Provide Medical Aid and Report Injuries

A. Duty to Provide Medical Aid

-

Requirement to Provide Medical Aid. Following any use of force, the officer using force or other officers present at the scene must immediately summon EMS and immediately provide medical aid, to the best of their skill and training, to any person that is:

- Injured;

- Claiming injury;

- Requesting medical attention;

- Exhibiting physical or mental distress; or

- Having difficulty breathing.

-

Exception. Officers are not required to call EMS for objectively minor injuries that can be treated with standard first aid (e.g. minor scrapes or bruises), but only if the officer is capable of providing that aid.

-

Requirement to Call EMS in Certain Situations. Officers must call EMS following the certain uses of force, regardless of the presence of visible injury or complaint of injury, if the use of force involved:

- Batons or other impact weapons;

- Tasers or pepper spray;

- Canine bites;

- Striking of the head (e.g. punching, kicking, hitting, impact against a hard object, etc.); or

- People known to or reasonably believed to be minors, elderly, physically frail or disabled, or pregnant.

-

Duration of Duty to Provide Medical Aid. The duty to provide medical aid continues until any injured individuals are either in stable condition or in the care of trained emergency medical professionals. Officers must continuously monitor a person’s condition and provide ongoing updates to EMS on the person’s condition.

-

Refusal of Medical Evaluation. Persons have a right to refuse medical evaluation. If an individual does so, that refusal must be documented in a report and booking form, and, where possible, witnessed by a second officer.

-

Requirement of Examination Prior to Detention. An injured person must not be admitted or held in detention without being examined and released by a physician or qualified health care provider. Whenever there is doubt concerning the need for medical attention, it should be resolved through examination of the person by an appropriate health care provider. Refusal of treatment shall be documented and verified by the officer and attending physician or health care provider.

-

Requirement of Examination Prior to Interrogation or Prisoner Processing for Certain Forms of Force. A person must be examined by an appropriate health care provider prior to interrogation or processing for purposes of detention when suffering from or complaining of injury or illness or when, among other instances, the use of the force on the person involved:

- Strike to the head with an impact weapon or other hard object;

- A prohibited restraint involving the neck or throat;

- Strike with a less-lethal weapon such as a TASER dart, ARWEN, or stingball; or

- A bite by a police canine.

B. Reporting Injuries

All injuries sustained due to a use of force must be documented on a booking form. Officers must document, at a minimum, the nature and location of the injury and how the injury occurred. Officers will not book a person who has or complains of an injury following the use of force unless they document that person has been evaluated by a medical professional, or has refused such evaluation, or that such evaluation was not needed because it involved a minor injury such as a minor scrape or bruise.

1.4 Duty to Safely Transport

A. Duty to Safely Transport

- Requirement to Safely Transport. Officers must ensure the safe transportation of all persons in their care. Officers must safely secure a restrained person in an upright position upon placing the person inside a vehicle. Officers who are transporting individuals have a duty to avoid placing the person’s body in a position that risks positional asphyxia, which occurs when the position of a person’s body prevents the person from adequately breathing.

- Handcuffs as Preferred Restraint. Handcuffs are the preferred restraint device for transportation. Officers must check any handcuffs placed on a person for tightness and to ensure they are double locked as soon as it is safe to do so prior to transport.

B. Prohibited Body Positions and Restraints

This policy expressly prohibits:

- The transportation of a person in a face-down position;

- The use of a “hog tie” restraint; and

- The use of “hobble” or other leg restraints to secure individuals to fixed positions inside a vehicle.

Endnotes

- Kristine Phillips, "Black Teen Who Was Slammed to the Ground By a White Cop at Texas Pool Party Sues for $5 Million," Washington Post (Jan. 5, 2017).

- Amelia McDonell-Parry & Justine Barron, "Death of Freddie Gray: 5 Things You Didn't Know," Rolling Stone (Apr. 12, 2017); Juliet Linderman & Curt Anderson, "Lawyer Says Fatally Injured Arrestee Lacked Belt," Detroit Free Press (Apr. 23, 2015).

- Id. Linderman & Anderson.

- Oliver Laughland & Jon Swaine, "Six Baltimore Officers Suspended over Police-Van Death of Freddie Gray," The Guardian (Apr. 20, 2015).

- Robert Pinckley, "The Right to Remain Silent: Law Enforcement and the Duty to Intervene," 56-DEC Tennessee Bar Journal 16, 18 (2020); Ashley Southall, "Daniel Pantaleo, Officer Who Held Eric Garner in Chokehold, Is Fired," New York Times (Aug. 19, 2019).

- See Pinckley, supra note 5; Ashley Southall & Johanna Barr, "Derek Chauvin Trial: Chauvin Found Guilty of Murdering George Floyd," New York Times(Apr. 21, 2021); Amended Complaint and Statement of Probable Cause at 3–4, State v. Chauvin, No. 27-CR-20-12646 (Minn. Dist. Ct. June 3, 2020).

- See, e.g., Smith v. Mensinger, 293 F.3d 641, 650 (3d Cir. 2002); Putman v. Gerloff, 639 F.2d 415,423 (8th Cir. 1981); Byrd v. Brishke, 466 F.2d 6, 11 (7th Cir. 1972). § 1983 is a source of procedural rights, providing a cause of action for vindication of constitutionally or federally conferred rights to those who have been deprived of them by persons acting under the color of the law, such as police officers. Because a person has the right to be free from excessive force under the Fourth, Eighth, and Fourteenth Amendments, the person’s excessive force claim against a police officer can be actionable under § 1983, irrespective of whether a police department’s policies contain a duty to intervene provision.

- See Delores Jones-Brown et al., "Am I My Brother's Keeper: Can Duty to Intervene Policies Save Lives and Reduce the Need for Special Prosecutors in Officer-Involved Homicide Cases?," 57 No. 5 Crim. Law Bulletin ART 1, § I, IV(B) (2021) (recognizing that, for duty to intervene policies to be effective, they must provide “specific guidance to intervening officers in terms of their expected behavior” and “address internal structural factors impact[ing] officer conduct” by “includ[ing] detailed and clear instructions about what is required for effective intervention.”); In Eric Garner’s case, the duty-to-intervene policy of the New York Police Department in effect at the time of Garner’s death did not provide guidance regarding “the specific conduct that is expected to satisfy the obligation to intervene.”

- Id. § X (explaining “[s]trong duty to intervene policies . . . specify that officers must use verbal and physical means to terminate the unlawful conduct of peers.”).

- Rank and file officers across multiple police agencies can be more inclined to report a fellow officer when they expect the offending officer’s misconduct to be met with harsher discipline. Sanja Kutnjak Ivković et al., "Decoding the Code of Silence," 29 CRIM. JUST. L. REV. 172, 172–178 (2016).

- Jones-Brown et al., supra note 8, § V (explaining effective duty to intervene policies “incentivize bystander officers to intervene by giving fair notice of the consequences at stake for failure to do so.”); see Colo. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 18-8-802(d) (West) (articulating that any officer who fails to intervene commits a class 1 misdemeanor); Colo. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 18-3-204(1)(a) (West) (classifying “knowingly or recklessly caus[ing] bodily injury to another person” as a class 1 misdemeanor); see, e.g., Minneapolis Police Department Policy and Procedure Manual Section 5-300 re Use of Force, § 5-301(III)(C)(2), at 7 (following the death of George Floyd, the Minneapolis Police Department revised its policy to explain that any officer who does not attempt to safely intervene when witnessing another officer exercise excessive force will “be subject to discipline to the same severity as if they themselves engaged in the prohibited, inappropriate or unreasonable use of force.”) (emphasis added).

- Jones-Brown et al., supra note 8, § X (concluding an effective duty to intervene policy “make[s] clear that officers who follow the policy will be protected from retaliation” because in the absence of such protection, police officers are less likely to summon the courage to intervene); see Milwaukee Police Department Standard Operating Procedure Section 460 re Use of Force, § 460.20 (acknowledging a bystander officer needs courage to prevent an offending officer from using excessive force).

- Taylor Romaine et al., "7 Rochester Police Officers Suspended over Daniel Prude's Death, Mayor Says," CNN (Sept. 4, 2020).

- Tom Dart & Joanna Walters, "Tulsa Police Under Scrutiny for Delayed Medical Aid Given to Terence Crutcher," The Guardian (Sept. 22, 2016).

- Ames Alexander & Anna Douglas, "Under Criticism, Charlotte Police Push to Get Faster Medical Help to Shooting Victims," Charlotte Observer (Apr. 25, 2019).

- See, e.g., Chen C-H et al., "Association Between Prehospital Time and Outcome of Trauma,"

PLoS Med. 17(10)(finding that every 10-minute delay in care increased the risk of severe disability or death by 6%). - See Jackson v. City of Joliet, 715 F.2d 1200, 1202 (7th Cir. 1983) (noting “a mere failure to rescue [someone in distress] is not tortious just because the defendant is a public officer whose official duties include aiding people in distress.”).

- Compare New Jersey Office of the Attorney General Use of Force Policy, § 6, at 19 (articulating police officers “shall promptly render medical assistance.”) and Houston Police Department General Order 600-17 re Response to Resistance, § 10, at 8 (explaining police officers “shall immediately request medical personnel to the scene.”) with City of Buffalo Department of Police Use of Force Policy Section 6, § 6.8(A), 6.10(A)(1) (omitting mention of when police officers “shall have the injured person taken for medical treatment” or when they “shall call for medical attention.”).

- For example, the American College of Surgeons trains people on how to treat hemorrhagic traumatic wounds in an online course. See Stop the Bleed.

- See, e.g., Training and Equipment, Tulsa Police Department (noting that every officer receives “specialized medical training” that “teaches evidence-based, life- saving techniques and strategies for providing the best trauma care in the field,” and offering officers the opportunity for full Emergency Medical Technician training); Bill Bush, "Columbus City Council Moves Forward on Funding for Reimagining Public Safety Initiative," Columbus Dispatch (Apr. 6, 2021) ; Emma Epperly, "Spokane Police Officers Train to Provide Critical First Aid as They Increasingly Arrive Before Medical Personnel," Spokesman-Review (Apr. 5, 2021).

- See, e.g. Joseph Serna, Police Commission Approves 8,000 Trauma Aid Kits for LAPD Officers, Los Angeles Times (Jan. 28, 2014); Bush, supra note 20; Epperly, supra note 20.

- See Minn. Stat. Ann. § 626.8475(b) (West) (requiring that officers who observe their colleague(s) employ excessive force report the incident within twenty-four hours); Colo. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 18-8-802(1.5)(b)(II) (West) (mandating that officers who witness their colleague(s) use excessive force report the incident within ten days of its occurrence); see, e.g., New Jersey Office of the Attorney General Use of Force Policy, § 5.4, at 18 (demanding an “officer who observes or who has knowledge of” unauthorized or excessive force to report the incident “before reporting off duty on the day the officer becomes aware of the misconduct.”).

- Documentation of an injured suspect’s refusal of medical aid is a common requirement across the country. See, e.g., San Francisco Police Department General Order 5.01 re Use of Force, § VI(B)(1)(a)– (B)(1)(a)(viii); Baltimore Police Department Policy 1115 re Use of Force, § 2, at 9; Portland Police Bureau Directives Manual Section 1010.00 re Use of Force, § 9.1; Utah Department of Public Safety Policy Manual Section 500 re Use of Force, § 500.4.2.

- Because there is no common-law duty to provide aid, officers are not liable for failing to render aid or assistance to those injured in the absence of a specific statutory or policy provision conferring a duty on them to provide aid. Jackson v. City of Joliet, 715 F.2d 1200, 1202 (7th Cir. 1983) (noting “a mere failure to rescue [someone in distress] is not tortious just because the defendant is a public officer whose official duties include aiding people in distress.”). However, merely having a written duty to render medical aid does not ensure compliance. See Jones-Brown et al., supra note 9, § I, IV(B). Rather, an effective duty to render medical aid provision must “give specific guidance to intervening officers in terms of their expected behavior” by specifying that a duty to render medical aid is mandatory and a failure to do so will result in disciplinary action. See id., at § I; see, e.g., New York City Police Department Patrol Guide 221-02 re Use of Force, at 2.