Batons and Other Impact Weapons

Clear and comprehensive policies on using batons and other impact weapons can protect officers and community members while providing important transparency and accountability.

- Introduction

- Key things to know

- Understanding Policies on the Use of Batons and Other Impact Weapons

- The Policy

- Endnotes

Introduction

Why are policies on using batons and other impact weapons important for police and the communities they serve?

Batons are often seen as the oldest and most fundamental police tool. While simple in design, they have featured frequently in significant moments where police have used force, including violent law enforcement actions during the civil rights movement and incidents like the 1991 beating of Rodney King by Los Angeles police officers. Powerful tools, used for compliance and defense, batons and similar impact weapons can quickly escalate to excessive—and even lethal—force.

This module examines the importance of comprehensive, well-structured policies governing the use of batons and other impact weapons. Our research reveals how batons, though generally considered less-lethal weapons by police, can be used to inflict serious harm and how they are sometimes employed by police to intimidate people in situations where their use may be unnecessary and inappropriate. Over the past several decades, many police departments across the U.S. reexamined their use of batons and implemented reforms to these use of force practices. The module discusses how clear policies on the use of batons and other impact weapons, that build on recent reforms, can further minimize harm, promote public safety, and strengthen community trust.

Downloads

Policy on Batons and Other Impact Weapons

Download the model policy on Batons and Other Impact Weapons.

Download PolicyFull Model Use of Force Policy

Download the Full Model Use of Force Policy – 10 detailed policies designed to help communities implement more effective use of force policies that enhance community safety while minimizing unnecessary force.

Open Full Model Use of Force PolicyKey things to know

- Batons and other impact weapons can inflict lethal injuries even though they are considered non-deadly force.

- Before striking a person with a baton or impact weapon, an officer must verbally warn the person and allow time for the person to comply with commands.

- An officer may not use a baton or impact weapon to strike a person who complies with commands or is not exhibiting aggression but is only actively or passively resisting.

- Unless deadly force is authorized, an officer must strike the arms or legs and avoid strikes to the head, neck, sternum, spine, groin, or kidneys.

- An officer using a baton or impact weapon to strike a person must be able to articulate the facts and circumstances that justify each and every strike on the person.

Understanding Policies on the Use of Batons and Other Impact Weapons

The baton, alternatively known as a club, billy club or night stick, is a deceptively simple weapon employed by police officers primarily as a means to enforce compliance or defend against aggression.[1] This instrument, heralded as the “oldest and most fundamental law enforcement tool,”[2] is valued within police ranks for its versatility and effectiveness in both defensive and counteractive scenarios.[3]

However, the image of the baton has been indelibly marked by its frequent appearance in some of the most resonant accounts and depictions of police using force since the dawn of the civil rights movement. The late Congressman John Lewis, a prominent civil rights leader, was participating in the 1965 Selma to Montgomery march when he sustained a fractured skull at the hands of police officers wielding clubs. The event, infamously known as “Bloody Sunday,” is encapsulated in numerous images of Alabama state troopers and sheriffs brandishing and using batons against peaceful protestors attempting to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge, including a visibly bloodied 25-year-old Lewis. Nearly 26 years later, the baton once again took center stage as news stations aired footage of Los Angeles Police Department officers striking Rodney King a shocking 56 times with a club.

These disturbing instances, Bloody Sunday and the beating of Rodney King, spurred significant societal change—the passage of the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the 1992 Los Angeles uprising, a series of riots and civil unrest ensuing after the acquittal of the four officers charged with using excessive force against King.

Following the beating of King, police departments across the country “looked critically and comprehensively at the use of force and its justifications, levels, and methods.”[4] Closer examinations of force practices, including the use of batons, led to a “wave of reforms—some of which are still works in progress.”[5] It became clear that the methods and tools of enforcement, often seen as merely tactical considerations, could, in fact, have profound societal impacts and implications for civil liberties.

The conversation around baton use has grown to encompass a range of pressing issues: the dangerous—and sometimes lethal—nature of batons and other impact weapons, the importance of officer training, the potential for batons to be used as instruments of intimidation, the challenges presented by the use of improvised impact weapons, and the necessity of special considerations for vulnerable populations and restrained individuals. These drive this module of the Model Policy, which is designed to balance the demands of officer safety with a firm commitment to the preservation of human life.

Regulating the dangerous—and sometimes lethal—nature of batons and other impact weapons

Research shows that individuals are at a higher risk of injury when officers use batons or other impact weapons than incapacitating devices like Tasers or pepper spray. While batons are considered less lethal weapons than firearms, these impact weapons can inflict serious harm and, when used improperly, have the capacity to result in death.[6] The inherently dangerous nature of the weapons demands that policies governing batons acknowledge this reality and set appropriate restrictions on their use.

Clearly communicating these risks to law enforcement officers through thoughtful policies is an essential step in mitigating the potential for misuse and unintended injury. The U.S. Department of Justice has asserted that any “adequate” use of force policy would “state clearly that a baton is capable of inflicting lethal injuries but may also be considered a lower level of force, depending on how it is used and the body part attacked.”[7]

Research by the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights recommends that officers should “understand that strikes to vulnerable body parts are considered lethal force because of their high risk of serious injury and death.”[8] While many police departments allow the use of batons as a lethal weapon when circumstances justify deadly force, these researchers propose an absolute prohibition on striking the head or other vulnerable body parts such as the neck, chest, spine, groin, or kidneys.[9]

The Model Policy seeks to strike a balance between a range of varying perspectives. While explicitly noting the weapon’s lethal nature, the policy acknowledges that officers may be confronted with extreme circumstances justifying the use of deadly force, in which case a baton could be the best option available. An absolute prohibition on the use of batons as a lethal weapon might also, inadvertently, encourage officers to more frequently resort to their firearms—a more lethal force option.

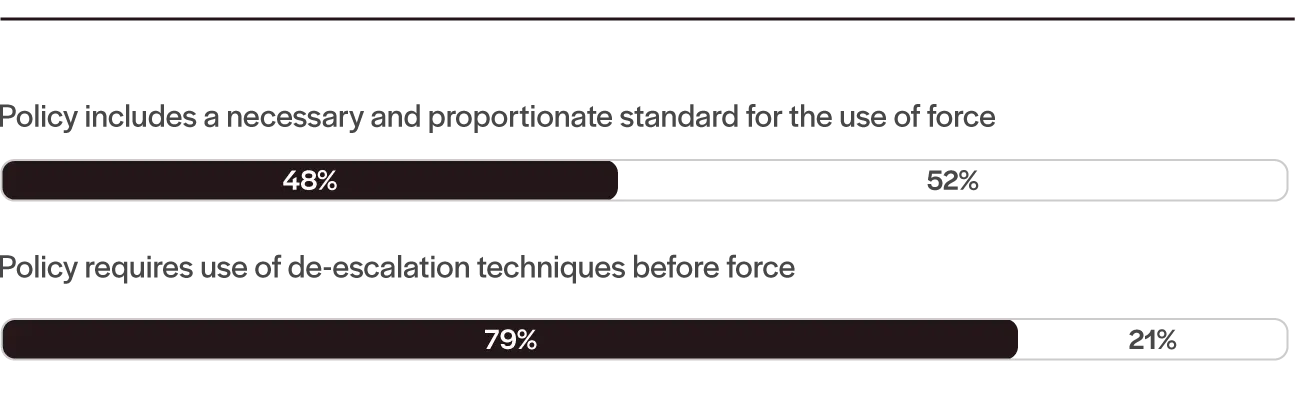

Key Force Regulations in Policies of 100 Largest U.S. Cities

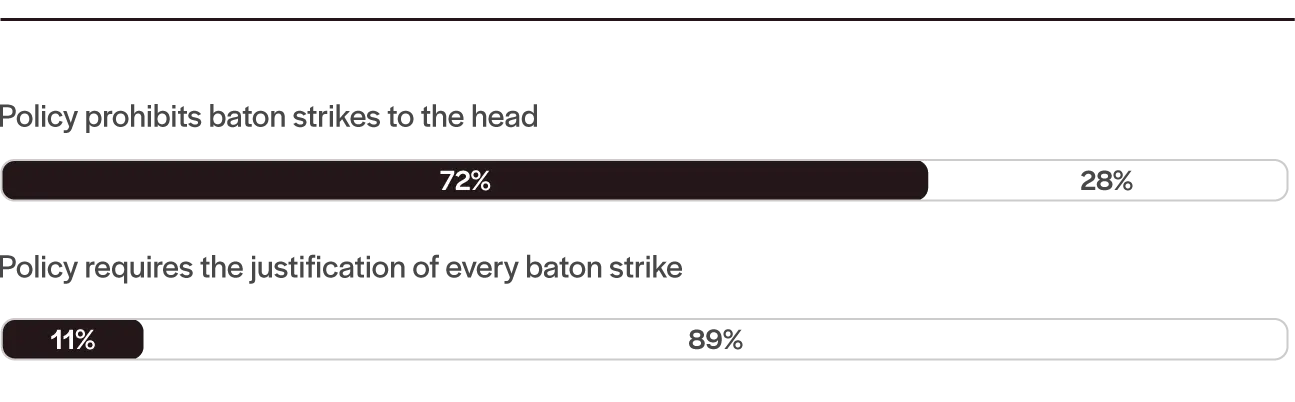

Baton Regulations in Policies of 100 Largest U.S. Cities

Importance of training on baton use and techniques

A 1967 Federal Bureau of Investigation manual for police officers on the “Technique and Use of the Police Baton” notes that “The officer who carries a baton as part of [their] equipment must be trained to use it properly,” (underlined in original).[10] Despite this decades-old admonition and the lethal risks posed by batons, some police departments do not require training on the weapons. Insufficient training on batons and impact weapons not only exposes a community to unnecessary risks, such as excessive force or unintended injuries, but it also exposes police departments and local governments to potential litigation stemming from misconduct claims. A clear understanding of when and how to appropriately use batons can significantly reduce these risks while simultaneously preserving officer and public safety.

Federal police monitors have also recognized the role training can play in reducing excessive force, injuries, and liability. When the U.S. Department of Justice found that the Baltimore Police Department was engaging in unconstitutional and discriminatory policing in 2016, the city negotiated a court-approved consent decree requiring the department to enact comprehensive policing reforms—including to its use of force policies and practices. This decree expressly stated, “Officers will be trained and certified for department-approved batons and espantoons (collectively “Impact Weapons”) before being authorized to carry Impact Weapons.”[11]

This module of the Model Policy adopts the Department of Justice’s approach and requires baton training for officers. However, the module goes beyond the Baltimore consent decree provision by mandating not just initial but annual baton training for officers. This requirement acknowledges the insights from further research and evidence, which underscore the importance of regular practice in reinforcing crucial techniques, as well as refreshing officers’ understandings of key rules and policies.

When police use batons to intimidate they are using force

Policing scholars and policymakers have debated whether particular uses of a baton, such as pounding it on the hood of a person’s car, are uses of force or, instead, should be considered an exertion of power, authority, or persuasion. These discussions overlook the strong potential for batons to be perceived by community members as symbols of intimidation. From a community member’s standpoint, the presence of a baton, even if not actively used against a person, can signal an implicit threat, and represent an intimidating show of potential violence.

The history of baton use in law enforcement is, in certain respects, interwoven with incidents of police brutality, as instances of misuse and excessive force—like the King beating—have served to create a societal association between these tools and undue violence. Conventional conceptions of police brutality include, among others, “threats to use force if not obeyed” and “prodding with a nightstick.” [12] Such displays, far from being passive, actually constitute a form of force. This module considers the use of a baton for intimidation to be a use of force and, therefore, subject to the Policy’s limitations on the use of force.

Should the use of improvised impact weapons be permitted?

Decisions about whether officers should be permitted to use improvised impact weapons, such as flashlights, require a challenging balancing of public safety and community interests. These objects, by their very nature, are not designed to be used as weapons[13] and officers typically receive no formal training on wielding them, thereby introducing a set of unpredictable risks. However, most officers and use of force trainers can conceive of circumstances where using this type of weapon to defend themselves or a bystander from attack might be necessary. And, at its core, the Model Policy seeks to discourage the use of firearms and more lethal forms of force unless they are absolutely necessary. Like a baton, an improvised impact weapon presents a less-lethal force option for an officer that finds themself in a dangerous situation.

Most police department policies reviewed by our research team tend to generally prohibit the use of improvised impact weapons. But these policies also typically authorize officers to use these weapons in exigent circumstances.[14] This module of the Model Policy includes an exception that permits the use of an improvised impact weapon in the rare and exigent circumstances where it is necessary and an officer is already authorized under the policy to use a baton or other conventional impact weapon.

Restricting the use of batons against vulnerable community members and restrained persons

It is important for use of force regulations to address the harms batons could inflict on vulnerable community members or individuals in defenseless positions. The implications of baton use against certain populations, such as the young and elderly, are particularly concerning given these individuals' heightened risk of serious injury. Furthermore, the use of batons against individuals who are already detained and restrained not only poses substantial injury risks, but also has the potential to significantly erode public trust.

Considering these issues, policies that merely state an officer may use a baton when a person is resisting—without accounting for variables such as age or vulnerability—can foster ambiguous interpretations. This can lead to an officer mistakenly believing they are authorized to strike an elderly person or a minor with the same force applied to a stronger, potentially more threatening, individual.[15]

Public trust in law enforcement—indispensable for maintaining law and order—relies heavily on the perceived legitimacy of police authority. And research supports the premise that the public is more likely to obey the law when they perceive those enforcing it as having legitimate authority.[16] This legitimacy is cultivated through treating individuals with dignity and respect, allowing individuals a voice during encounters, maintaining neutrality and transparency in decision-making, and conveying trustworthy motives.[17] Misuse of physical control equipment, such as batons, especially against vulnerable populations, can significantly undermine this trust, potentially leading to the public delegitimizing police departments’ authority to enforce laws.[18]

Reviewing more than 100 use of force policies from departments across the U.S., the Model Policy’s researchers found that only around a dozen policies discussed the considerations of using batons against vulnerable populations. Policies that fail to distinguish between vulnerable and non-vulnerable individuals may cause confusion for officers trying to determine when the use of a baton is “reasonable.” For instance, using a baton against a 75-year-old protester exhibiting active aggression may not be reasonable while the weapon’s use against a more imposing individual, like the 6-foot-6 former Olympic athlete who resisted police officers’ efforts to remove him from the U.S. Capitol Rotunda during the January 6th riot, might meet a reasonableness standard if he was exhibiting the same behaviors.[19]

Many use of force policies are also silent on the use, or prohibition, of batons on handcuffed individuals. This use of force poses tremendous risks to a person as well as the police department because it is widely understood to be excessive. The Model Policy safeguards against these risks by prohibiting the use of batons on restrained individuals, even if they fail to comply with an officers’ commands.[20] Only in a rare and exceptional situation, where a handcuffed person continues to present an imminent threat to the safety of the officer or another person, is the use of a baton permitted.

The Policy

1.1 – Key Concepts and Definitions

A. Key Concepts:

- Batons and other impact weapons may be effective tools for strikes, jabs, holds and blocks, but they deliver blunt force and can cause serious bodily harm and even deadly injuries.

- Baton or impact weapon strikes to the head, neck, sternum, spine, groin, or kidneys are lethal force.

B. Definitions:

-

Available Information: The information that was obtainable or accessible to an officer at the time of the officer’s decision to use force. When an officer takes actions that hasten the need for force, the officer limits their ability to gather information that can lead to more accurate risk assessments, the consideration of a range of appropriate tactical options, and actions that can minimize or avoid the use of force altogether.

-

Baton: An Impact Weapon used for blocking, jabbing, striking, or to apply control holds. The Department authorizes the following types of Batons for use: the Expandable Baton and the Crowd Control Straight Baton:

a) Expandable Baton: an expandable metal Baton; generally 21-26 inches in length with the AutoLock mechanism.

b) Crowd Control Straight Baton: A wooden or synthetic composite baton generally 24-36 inches in length to be used in crowd control situations.

-

Impact Weapon: Any object, whether a tool or fixed object (such as a hard surface), that officers use to interrupt or incapacitate a person. This includes, but may not be limited to, Batons.

-

Improvised Impact Weapon (IIW): The use of instruments, other than Department-authorized Impact Weapons, as a weapon for the purpose of striking or jabbing.

-

Lawful Objective: Limited to one or more of the following objectives:

a) Conducting a lawful search;

b) Preventing serious damage to property;

c) Effecting a lawful arrest or detention;

d) Gaining control of a combative individual;

e) Preventing and/or terminating the commission of a crime;

f) Intervening in a suicide or self-inflicted injury; and/or

g) Defending an officer or another person from the physical acts of another.

-

Necessary: Force is necessary only if there are no other available non-force options or less-forceful options to achieve a lawful objective.

-

Reportable Force: A use of force that must be reported to the Department.

-

Resistance: Officers may face the following types of resistance to their lawful commands:

Passive Resistance: A person does not attack or attempt to attack the officer or another person, and does not attempt to flee, but fails to comply with the officer’s commands. Examples include, but may not be limited to, going limp, standing stationary and not moving following a lawful command, and/or verbally signaling their intent to avoid or prevent being taken into custody.

Active Resistance: A person moves to avoid detention or arrest but does not attack or attempt to attack the officer or another person. Examples include, but may not be limited to, attempts to leave the scene, fleeing, hiding from detection, physical resistance to being handcuffed, or pulling away from the officer’s grasp. Verbal statements, bracing, or tensing alone do not constitute Active Resistance. A person’s reaction to pain caused by an officer or purely defensive reactions to force does not constitute Active Resistance.

-

Aggression: Officers may face the following types of Aggression:

Active Aggression: A person’s attempt to attack or an actual attack on an officer or another person. Examples include, but may not be limited to, exhibiting aggressive behavior (e.g., lunging toward the officer, taking a fighting stance, striking the officer with hands, fists, kicks). Neither Passive nor Active Resistance, including fleeing, pulling away, bracing, or tensing, constitute Active Aggression.

Aggravated Aggression: A person’s actions that create an objectively reasonable perception on the part of the officer that the officer or another person is facing imminent death or serious physical injury as a result of the circumstances and/or nature of an attack. Aggravated Aggression represents the least encountered but most serious threat to the safety of officers or bystanders.

-

Totality of Circumstances: The totality of the circumstances consists of all facts and circumstances surrounding any event.

1.2 – Requirements for Issuance and Carrying of a Baton

A. Issuance

A Baton may be issued only to officers who have been trained on this Department’s use of force policies, have demonstrated the required proficiency in the use of the weapon, and become trained users of the Baton.

B. Training and Qualification

Officers carrying a Baton must receive initial and annual training.

C. Carrying

Officers may carry and use only Department-authorized Batons. Any modifications to an issued Baton including, but not limited to, coring, filling, notching, adding protrusions to, or re-painting are prohibited.

D. Prohibited Batons/Impact Weapons

This policy strictly prohibits the carrying of blackjacks/slapjacks, weighted gloves, brass knuckles, iron claws, or any other unauthorized impact weapons.

1.3 – Authorization for Use of a Baton or Other Impact Weapon

The following actions with a Baton constitute a use of force:

- Use of a Baton as a weapon.

- Use of a Baton to deliver a physical strike or jab to any part of a person.

- Any physical contact or threat of contact by a Baton that causes or threatens to cause pain or injury to another person.

- Any physical contact or threat of contact by a Baton that results in restraint or physical manipulation of the movement of a person.

- Unholstering or displaying a Baton (including unfolding a Baton), when engaged with an individual.

A. Authorization for using Baton to guide, escort, or control

This use of a Baton is authorized only when there is a Lawful Objective, lower-level force options have been ineffective or are not available, the officer issues a verbal warning before using force, and the use of the Baton is necessary to guide, escort, or control persons exhibiting Passive or Active Resistance, without using the Baton to deliver strikes or jabs.

B. Authorization for Baton strikes or jabs

This use of a Baton is authorized only when there is a Lawful Objective, lower-level force options have been ineffective or are not available, the officer issues a verbal warning before using force, and the use of the Baton is necessary to control a person whose actions become Active or Aggravated Aggression to the point that they prevent an officer from making an arrest or pose a substantial risk of causing imminent bodily harm.

1.4 Standard for Using a Baton or Other Impact Weapon

A. Standard for using Baton

Any use of a Baton must be limited to the minimum amount of force the officer believes is feasible to carry out a Lawful Objective, consistent with Available Information, and must be proportional to the totality of the circumstances. An officer must be able to articulate the facts and circumstances that justify each and every Baton strike on a person and, once the person is no longer exhibiting Active or Aggravated Aggression, the officer must immediately stop striking the person.

B. Strike target areas

When using a Baton or other impact weapon to strike a person, the officer should strike only the arms or legs. Strikes to the torso, in areas other than the sternum, spine, groin, or kidneys, are permitted, when necessary, based on the totality of the circumstances, but should be otherwise avoided due to the increased risks of serious physical injury and striking a prohibited area (e.g. the sternum, spine, or kidneys).

C. Baton strikes as Deadly Force

Strikes to the head, neck, sternum, spine, groin, or kidneys are prohibited. The only exception to this prohibition is when the use of deadly force is authorized under this policy.

D. Improvised Impact Weapons (IIWs)

IIWs are instruments, other than Department-authorized Impact Weapons, as a weapon for the purpose of striking or jabbing. This policy prohibits the use of an IIW, except in rare and exigent circumstances that would authorize the use of a Department-authorized Baton and:

- The officer has exhausted authorized force options, does not have such options available to them, or believes that such options will be ineffective, and this belief is consistent with available information; and

- The officer has an articulable, compelling need to use the IIW based on the totality of the circumstances; and

- The officer who uses an IIW must transition from the use of such a weapon to an authorized force option as soon as possible.

E. Prohibited uses of a Baton

-

To strike a person who is compliant or who is exhibiting only Passive or Active Resistance.

-

To strike a person who is handcuffed or restrained, except in the rare and exigent circumstances where the person displays combative and/or violent behavior and lesser means or attempts to control the person such as Physical Controls have failed.

-

To strike a person who is:

- a child;

- elderly;

- believed to be pregnant;

- visibly frail;

- under the effects of a medical or behavioral health crisis; and/or

- in danger of falling from a significant height.

1.5 – Duty to Provide Medical Aid

A. Requirement to Provide Medical Aid

Following any use of physical force, the officer using force or other officers present at the scene must immediately summon EMS and immediately provide medical aid, to the best of their skill and training, to any person that is:

- Injured;

- Claiming injury;

- Requesting medical attention;

- Exhibiting physical or mental distress; or

- Having difficulty breathing.

1.6 – Reporting and Review for Baton Use of Force

A. Reporting Requirements

- Using a Baton or other Impact Weapon in a manner that constitutes a use of force is Reportable Force. The officer must immediately notify their supervisor and complete a use of force report.

- Officers must justify each strike with a Baton or IIW on their use of force report.

B. Reviewing Baton use of force

Supervisors must review all incidents of Baton strikes.

Endnotes

- “Nightstick,” Merriam-Webster.com Thesaurus.

- Ken Peak & Jenny D. Hubach, "The World’s Oldest Tool for Professional Law Enforcement: Historical and Legal Perspectives on the Police Baton," 7 The Justice Professional 1 (1992).

- Federal Bureau of Investigation, "Technique and Use of the Police Baton," 1 (1967) (“The police baton, in the hands of an officer who has been trained in its use, is a very formidable weapon for defense and counterattack.”).

- Geoffrey P. Alpert & Michael R. Smith, "Police Use-of-Force Data: Where We Are and Where We Should Be Going," 2 Police Quarterly 57-58 (1999).

- Richard Winton, "How the Rodney King Beating ‘Banished’ the Baton from the LAPD," Los Angeles Times (March 2, 2016).

- The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, "New Era of Public Safety: A Guide to Fair, Safe, and Effective Community Policing," 138 (2019).

- See U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Civ. Rights Div., "Investigation of the New Orleans Police Department," 1 (2011).

- The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, "New Era of Public Safety: A Guide to Fair, Safe, and Effective Community Policing," 138 (2019).

- New Era 138.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation, Technique and Use of the Police Baton 1 (Sept. 1967).

- Consent Decree, United States v. Police Department of Baltimore, No. 1:17-CV-99-JKB, 51 ¶ 149 (D. Md. 2017).

- William A. Geller & Hans Toch, Police Executive Research Forum, "And Justice For All: Understanding and Controlling Police Abuse of Force," 16 (1995).

- See T.C. Coxx, J.S. Fraughn, and W.M. Nixon, "Police Use of Metal Flashlights as Weapons- An Analysis of Relevant Problems," (1985) (abstract only). For example, “[p]olice metal flashlights are often used defensively to strike blows to the head to subdue persons resisting arrest.”

- Seattle Police Department Manual, 8.300 Use of Force Tools, (2021).

- Brandon Garrett & Seth Stoughton, "A Tactical Fourth Amendment," 103 Virginia Law Review 211, 274.

- See Tom Tyler, "Why People Obey the Law," Princeton University Press (1990).

- New Era 94.

- See CBS Los Angeles, "Video Allegedly Shows VA Police Officer Using Baton to Beat Suspect 32 Times," (Match 2, 2022).

- See Julian Mark, "Buffalo officers can return to duty after pushing 75-year-old protester," (April 22, 2022) Washington Post (reporting that two Buffalo police officers pushed a 75-year-old human rights demonstrator causing him to hit his head on the sidewalk and lie motionless while bleeding from his head.); The Associated Press, "Klete Keller, Olympic gold medalist swimmer, gets 6 months in home detention for Jan. 6 Capitol riot," (Dec. 1, 2023).

- The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, "New Era of Public Safety: A Guide to Fair, Safe, and Effective Community Policing," 138 (2019).