Canines

Clear and comprehensive policies on using canines can protect officers and community members while providing important transparency and accountability.

Introduction

Police Canines: Why are policies on using dogs important for police and the communities they serve?

In the spectrum of law enforcement strategies, police canines stand out as a unique tool. They represent a blend of trained animal behavior and controlled police action, with the potential to cause serious injuries—or even death—and the capacity to provoke intense psychological responses. This module discusses the range of policies and considerations related to deploying canines. It examines everything from prohibitions against using canines in crowd management to the application of specific deployment techniques like “find and bark” or “bark and circle” in an attempt to mitigate the risks tied to using dogs.

Extensive research underlying this module emphasizes the need for rigorous training, certification processes, and thorough reporting on canine uses of force to ensure accountability and community safety. The framework in this module goes beyond minimizing risks; it also addresses the historical misuse of canines, notably against Black communities. By acknowledging this history and crafting clear and robust use of force policies, the Model Policy seeks to redefine the role of canines for the law enforcement agencies that utilize them in a manner that is not only safer and fairer but also builds community trust.

Downloads

Full Model Use of Force Policy

Download the Full Model Use of Force Policy – 10 detailed policies designed to help communities implement more effective use of force policies that enhance community safety while minimizing unnecessary force.

Open Full Model Use of Force PolicyKey things to know

- When an officer uses a police canine to search for and apprehend a person, it is a use of force. The officer must understand how the canine’s mere presence can heighten already tense situations and that the dog can inflict life-threatening or life-altering injuries.

- An officer may only use a canine when apprehending a person who has committed a serious crime and it is likely that person will seriously harm the officer or others.

- Before commanding a canine to “bite and hold” a person, a canine handler must determine that all non-force options have failed and that it is likely the person will seriously harm the officer or others.

- Canines should not be used for routine calls or arrests, or for crowd management. An officer may not use a canine solely to intimidate, coerce, or frighten a person.

- Canines and their handlers must receive regular training, their every use must be documented rigorously, and their deployments must be reviewed by supervisors and trainers.

Understanding Policies on the Use of Canines

Police departments across the United States deploy canines for diverse roles including search and rescue, drug sniffing, explosive detection, crowd management, and suspect apprehension. While canines are not traditionally considered weapons, they can indeed be used by police to apply force. The collaboration and unique team dynamic formed between a human officer and a canine represents a specialized aspect of law enforcement strategy, reflecting a longstanding tradition in policing dating to the early 1900s.[1] However, policing’s increased reliance on canines in engagements with criminal suspects has brought forward significant policy considerations that require critical analysis.

Canine uses of force should be analyzed under the same critical standards as traditional methods of force such as Tasers, batons, and other impact weapons. Data indicate that non-lethal injuries occur at significantly higher rates from canine deployment than from these other tools.[2] There is also a long and troubling history in the United States of using canines in connection with racial violence, particularly against Black people—from 19th-century “slave dogs” to the use of dogs against civil rights protestors in the 1960s.[3] Studies suggest that Black individuals constitute a disproportionate share of people bitten by police canines, making it crucial that strict use of force standards are applied to canine uses of force.[4]

Policing authorities argue that canines serve as valuable law enforcement tools that can enhance officer and public safety.[5] Their speed and extraordinary senses can be harnessed to track and locate drugs, explosives, dead bodies, and hiding suspects.[6] But an important debate is emerging about whether canines should still be used by police forces for non-explosive detection purposes, with leading use of force experts arguing that “criminal apprehension” canines should be retired from police service because their dangers outweigh their benefits.[7]

The arguments advanced by those criticizing the continued use of canines for apprehensions echo key principles of the Model Policy—prioritizing the value and dignity of human life and minimizing the harms faced by Black and brown communities. This module recognizes that many police departments across the U.S. may continue to use canines for search and apprehension purposes and these agencies can benefit from clear guidance on how the animals can be effectively utilized. For police departments that retain their “criminal apprehension” canines, the Model Policy recommends a set of restrictive policies aiming to minimize both physical and psychological injuries and enhance trust between law enforcement and communities.

Examining the history of canine misuse by police against Black communities

The use of canines by law enforcement against Black communities has a harrowing history that traces its roots back to the era of slavery. During the 19th century, slave owners used dogs to hunt escaped slaves and suppress attempts at rebellion. This practice continued into the civil rights movement, with police dogs unleashed on peaceful Black protesters.

Decades later, some police departments have continued to weaponize and disproportionately use canines against Black Americans.[8] A nearly two-year review by the U.S. Department of Justice of the Louisville Metro Police Department in Kentucky revealed disturbing findings about the department’s use of canines, specifically against Black residents. The investigation uncovered a disproportionate targeting of Blacks that often occurred with minimal justification or oversight and prompted immediate calls for reform to the police department’s canine operations.

The Justice Department’s report described a highly troubling incident involving a 14-year-old Black teen who was lying face down in the grass, pleading for help, when a Louisville officer ordered his canine to bite the boy at least seven times without warning. Officers stood over the teen for nearly 30 seconds while the dog gnawed on his arm and at one point shouted, “Stop fighting my dog!” despite video showing the boy lying still with one arm behind his back and the other arm in the dog’s mouth. The police department’s records on the incident, which were obtained by investigative journalists, stated that the youth “did not give himself up to police” and that the dog was removed “once compliance was gained,” even though a video showed otherwise.[10]

Another recent canine incident in Ohio illustrates the scope of the violence and harm. Jadarrius Rose, a 23-year-old Black truck driver, was pursued by state and local police after they attempted to pull him over for a missing mudflap on his trailer. Video shows that as he tried to surrender on the side of the highway with his hands in the air, a Circleville, Ohio canine handler approached him as a state trooper yelled repeatedly at the handler “Do not release the dog with his hands up!” Ignoring this order, the handler released the canine which proceeded to bite and injure Rose.

These alarming contemporary incidents further an unsettling historical legacy of police misusing canines against Black Americans. To prevent more undue harm and injustice, police agencies must deliberate on the methods and circumstances under which canines are employed, especially in their interactions with Black communities.

When should the use of canines be prohibited

An effective approach to lowering the risk of a dog harming a person, bystander, or officer, is limiting the use of canines to situations where they are necessary. Determining the reasonableness of a deployment of a canine—a standard used by federal courts to gauge an officer’s civil and criminal liability for unconstitutional force—largely hinges on specific facts and circumstances. But the Model Policy insists that police department policies should categorically prohibit deployments in certain situations based on significant policy considerations.

A primary consideration involves carefully weighing—and avoiding—the risk of serious injury to a person, bystander, or officer. When this risk of injury surpasses the threat posed by an individual, canines should not be deployed. In deploying a canine, police necessarily increase the likelihood of a person being injured by a canine bite.[11] For this reason, canines should not be used for routine calls and arrests that do not present heightened danger to officers and other community members. Special considerations for young, elderly, or pregnant individuals also dictate that canines should not be used against members of these groups, even when the use of force is otherwise permitted, unless officers have no feasible alternatives.

Similarly, canines should never be used on subjects who are handcuffed or otherwise restrained.[12] The use of force is not permitted under these circumstances and canines may create additional stress and potentially aggravate a situation. Canines should also not be used to physically search a person for narcotics or contraband. Officers can perform physical searches of a person more safely and accurately.[13]

In crowd management situations, many police departments prohibit the use of canines unless there are exigent circumstances or officers obtain special authorization. For example, the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department’s use of force policy restricts the use of canines while preserving an “emergency” exception for when the department engages in “an all-out police effort to rescue isolated officers or citizens in danger of being injured or killed.”[14] The Model Policy bans the use of canines for crowd management but also recommends against including an exception for exigent circumstances that permits the use of canines to address challenges created by large groups of people. Exigent circumstances that police departments typically rely on to support the use of canines—like retrieving an isolated officer—necessarily involve volatile and inflammatory situations where human police officers would be better-suited to maintaining a baseline level of control.

Additionally, the use of canines in crowd management settings creates psychological effects that can be counterproductive.[15] Many people react to dogs—and especially police canines—with fear, and fear does not necessarily lead to the type of rational decision-making that officers depend on to keep peace and maintain control over a crowd. In other words, introducing canines in the face of a protesting or riotous crowd could exacerbate the volatility and inflammatory nature of the situation.[16] Police departments have also misused canines as a crowd management tool against groups organizing for societal progress[17]—such as during the civil rights movement, when law enforcement in the South used canines and fire hoses to disperse groups of Black people protesting racial segregation.[18]

Importantly, the Model Policy also prohibits the use of a canine solely to intimidate or coerce. The New Jersey Attorney General’s Office recently consulted with local Black community members and groups in revising the state’s use of force policy, and these constituencies strongly recommended that the revised policy prohibit the use of dogs to intimidate people, particularly given the history of canine use in these communities.[19]

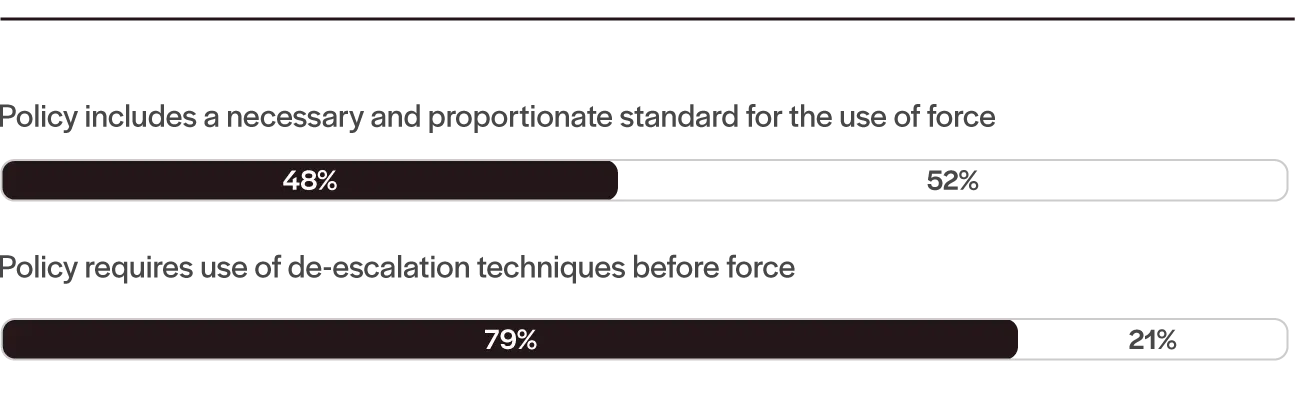

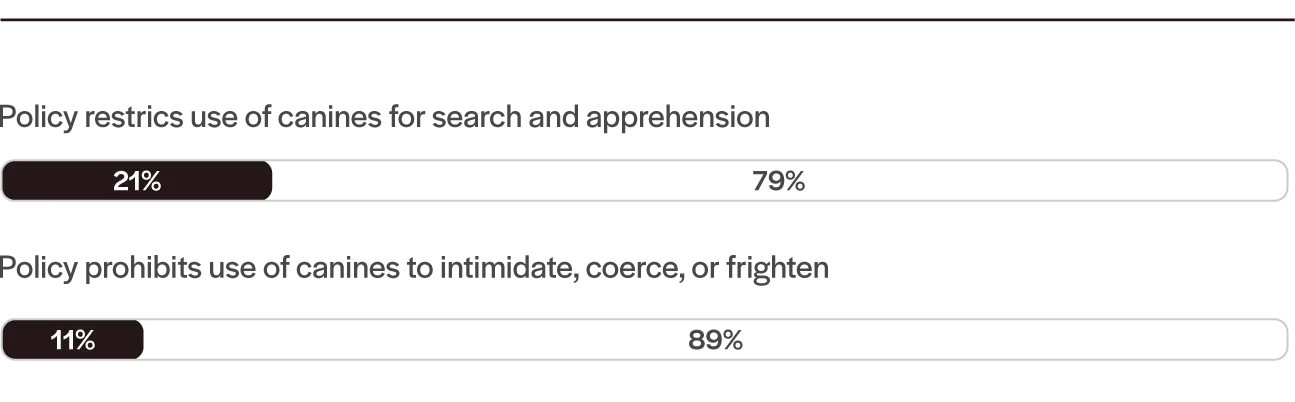

Key Force Regulations in Policies of 100 Largest U.S. Cities

Canine Regulations in Policies of 100 Largest U.S. Cities

The Model Policy’s approach to authorizing the use of canines

Canine bites can cause severe injuries, or even death, to individuals, bystanders, and dog handlers or other officers. Because of these risks, the Model Policy recommends that police department policies carefully outline their authorized uses of canines. Under the Model Policy’s approach, canines should be primarily used to detect contraband, explosives, and other crime scene evidence. The Model Policy also permits the use of canines to, in a limited set of circumstances, search for individuals and, in a very restricted set of circumstances, apprehend people that pose an imminent threat of harm to officers or others. In these situations where the potential for physical contact between a canine and a person significantly increases, our research supports applying strict use of force standards to canine uses of force.

Canine searches and apprehensions

Policies should clearly articulate that canines primarily serve to detect contraband, explosives, and other crime scene evidence. Canines should not be used in situations where individuals are suspected of committing minor crimes. This common-sense limitation, however, has yet to take hold. A 2020 investigation by the Marshall Project found that many canine bites target people in those circumstances and that these bites can cause unpredictable and life-threatening injuries.[20]

Instead, the Model Policy limits the use of a canine to search for a person to when the person has committed or is committing a serious offense and when the balance of factors relating to law enforcement goals, safety, and risks support the use of a canine.[21] The Policy stresses that a handler must prevent canine contact with a person during an authorized canine search, as opposed to certain authorized canine apprehensions where physical contact is anticipated, and accordingly should determine whether to proceed with the canine on-lead or off-lead.

Before using a canine to apprehend a person, police departments should impose additional requirements, including that the person poses an imminent threat of harm to the officers or others, that the standards for the use of force have been met, and that alternative tactics (including less severe force options) have been exhausted or are not safe and feasible. Otherwise, circumstances do not justify the risk to human life involved in the commonly used “bite and hold” technique, where the dog bites a person and then holds the individual with its mouth until officers establish physical control.

Using the “find and bark” or “bark and circle” techniques

To preserve human life, the Model Policy requires canines to be trained to use “find and bark” or “bark and circle” techniques when searching for individuals and apprehending them. These methods train a canine to alert a handler to the subject of a search by barking as a first response, and then circling and waiting until the handler arrives.[22] One reason the Model Policy recommends this approach is that research demonstrates that canine deployments result in higher rates of hospital visits than any other types of force used by police.[23] In Sacramento, California 30% of the police department's use of force cases over a certain period involved a canine.[24] After the Los Angeles Police Department changed its canine policy from utilizing the “bite and hold” technique to a “find and bark” method, the agency saw a significant drop in injuries and hospitalizations.[25] Once a handler determines that the preconditions for deploying a canine have been satisfied, the Model Policy requires the handler to give clear verbal warnings before using a canine and as the canine is deployed. Verbal warnings are an essential de-escalation tactic stressed throughout the Model Policy and provide a person with the opportunity to comply.

Importance of training for canines and their handlers

Effectively controlling the behavior of a canine requires specialized skill and knowledge rooted in science. Police handlers train extensively with their canines, honing the skills of the handler and their dog, but only a minority of use of force policies feature written requirements for annual canine training and certification. The Model Policy recommends that use of force policies have clear requirements for these training and certification processes that often cover a range of topics from apprehension techniques to drug detection and situational tactics. For these reasons, the Model Policy also requires a minimum of 20 hours per month of training for both canines and their handlers, as well as an annual certification process, an approach that aligns with law enforcement industry recommendations.[26]

Canines can and do regularly injure people, and when trained, they can bite with a force much greater than an average dog bite.[27] Thus, it is important for an officer to regularly train with their canine and appreciate that, even though the canine is a living, breathing animal, it is effectively a weapon when it is deployed to restrain a person. Training programs for handlers and canines should recognize these realities and, to the degree possible, resemble the training approaches for other police weapons that emphasize the gravity of choosing to employ the weapon. Adequate training can provide handlers and their canines with tactical options to address different situations and increase the likelihood that the canine team—and particularly the canine—will react appropriately to a given scenario.

Training is also important for more reliable drug detection. Historically, canines do not have high accuracy in drug detection with false alerts, when accurately documented, potentially exceeding 50 percent.[28] With more training, however, canines can potentially develop sufficient skills to fulfill their law enforcement agency’s goals.

Reporting on canine uses of force

The Model Policy contains detailed provisions on reporting about uses of force involving canines and reviewing the appropriateness of these canine deployments. Many police department use of force policies require written documentation each time that a handler deploys a canine, whether for detecting or apprehending an individual. This documentation serves important purposes because the canine’s actions often end up offered as evidence in court.[29] Prosecutors, for instance, regularly introduce evidence that a canine detected drugs or explosives. Documenting these events involving the use of detection dogs can be crucial to ensuring a successful prosecution.[30]

While evidence of a detection canine’s satisfactory performance in a certification or training program can provide prima facie proof of the canine’s reliability,[31] a criminal defendant “may contest the adequacy of [the] certification or training program, examine how the dog (or handler) performed in the assessments made in those settings, introduce evidence of the dog’s (or handler’s) history in the field, or ague that circumstances surrounding a particular alert may undermine the case for probable cause.”[32] Put another way, if a canine’s handler fails to document the dog’s performance, this could be used to attack the canine’s credibility. A strong record of performance, on the other hand, can buttress the canine’s credibility.

Police departments should track the performance of their canines as they track the performance of their officers. If a canine has a history of unreliability or posing risks to the public,[33] promptly and accurately documenting the canine’s behavior serves as the best way to ensure the department provides the canine with more training or responsibly decommissions the dog. Accordingly, the Model Policy requires handlers to document every deployment of a canine, regardless of whether a bite or injury occurs.[34]

Reviewing and investigating canine deployments

Documenting canine deployments serves particularly important purposes when bites or injuries occur. The documentation should be reviewed by supervisors to assess the deployment's appropriateness. Additionally, people who are injured by canines may introduce the evidence in a civil rights lawsuit against the officer, department, and/or municipality.

Documenting the injury and surrounding circumstances helps factfinders—like a police chief, judge, or jury—assess the reasonableness of the canine deployment. Since injured individuals may be unable to document their injuries—especially if they are directly taken into custody—requiring the handler or another officer to document the event ensures that those evaluating the appropriateness of the use of force will have the information they need to make this determination.[35]

The Policy

1.1 – Key Concepts and Definitions

A. Key Concepts:

- Canines should be primarily used to search for contraband, explosives, and other crime scene evidence.

- This Department also permits the use of canines to, in a limited set of circumstances, search for individuals and, in a very restricted set of circumstances, apprehend individuals that pose an imminent threat of harm to officers or others.

B. Definitions:

-

Available Information: The information that was obtainable or accessible to an officer at the time of the officer’s decision to use force. When an officer takes actions that hasten the need for force, the officer limits their ability to gather information that can lead to more accurate risk assessments, the consideration of a range of appropriate tactical options, and actions that can minimize or avoid the use of force altogether.

-

Canine Search: When an officer uses a canine to search for a person. There are two types of Canine Searches:

a) Tracking Search: When a canine handler deploys a dog to locate a person who has fled a crime scene. This may be done on- and off-lead.

b) Contained Search: When a canine handler deploys a dog to search within a contained area, i.e., a building or fenced lot, where a person is reasonably expected to be hiding. This may be done on- and off-lead.

-

Canine Apprehension: When officers deploy a canine that has a clear and defined role in the capture or surrender of a person. Statements or actions made by the person during or after the arrest provide the basis for determining whether the person has surrendered. The mere presence of a canine at the scene of an arrest, where the canine had no active role in the arrest, is not a Canine Apprehension.

-

Direct Apprehension: When a canine handler commands their dog to bite and hold a person that the handler has in sight.

-

Lawful Objective: Limited to one or more of the following objectives:

a) Conducting a lawful search;

b) Preventing serious damage to property;

c) Effecting a lawful arrest or detention;

d) Gaining control of a combative individual;

e) Preventing and/or terminating the commission of a crime;

f) Intervening in a suicide or self-inflicted injury; and/or

g) Defending an officer or another person from the physical acts of another.

-

Necessary: Force is necessary only if there are no other available non-force options or less-forceful options to achieve a lawful objective.

1.2 – Authorization and Standard for Canine Searches and Apprehensions

A. Authorization for Canine Search

A canine handler may use a canine to search for a person, or for officer safety during a search for a person, only in the following circumstances:

-

The officer has probable cause that the person has committed one of the following offenses or a valid arrest warrant exists for that alleged conduct:

Felony Offenses

- Burglary, not including trespass with a non-violent secondary offense

- Robbery, not including thefts that are accompanied by a low-level assault

- Homicide

- Serious assault

- Kidnapping

- Arson with threat of harm to people

- Domestic violence offenses

- Serious sexual assault

- Drive-by shooting, not including unlawful discharge of a firearm

Misdemeanor Offenses

- Domestic violence assault

- Domestic violence order violations that are subject to mandatory arrest—violations must involve the person’s physical presence at the victim’s location or a threat of harm; or

-

A supervisor approves the use of a canine in a situation where the canine handler has a reasonable belief that the person is armed with a firearm or weapon capable of causing substantial bodily harm, great bodily harm, or death, or poses an imminent threat of harm to the public.

B. Avoiding Physical Contact During Canine Search

A canine handler must ensure their canine avoids making physical contact with a person during an authorized Canine Search, as opposed to certain authorized Canine Apprehensions where physical contact is anticipated, and, accordingly, must determine whether to proceed with the canine on-lead or off-lead.

C. Authorization for Canine Apprehension

A canine handler may use a canine to apprehend a person through a Direct Apprehension—commanding their dog to bite and hold a person—only when all the following conditions are met:

- The officer has probable cause that the person has committed one of the above listed felony or misdemeanor offenses, or a valid arrest warrant exists for that alleged conduct; and

- The person poses an imminent threat of harm to the officer or others; and

- The officer has exhausted all alternative tactics that were safe and feasible. These alternatives may include identifying as a police officer, ordering the person to come out of hiding and warning the person that a police dog will be released, and they may be bitten if they do not voluntarily comply, and then waiting a reasonable amount of time for the person to comply, or using a lower level of force.

D. Considerations for a Canine Deployment

In deciding whether to deploy a canine for a Canine Search or a Canine Apprehension, officers should consider whether the totality of the following factors support the use of the canine:

- Severity of the suspected offense;

- Potential danger to bystanders if the canine is or is not deployed, including;

- Whether the person is known to be in possession of a weapon;

- Ability of the person to understand and comprehend verbal warnings;

- The person’s known or perceived age;

- Mental health, and/or other disabilities; and

- Availability of less-lethal force options.

E. Advance Briefing and Planning with On-Scene Officers

Before deploying a canine, the handler must receive briefing about the incident from on-scene officers and should coordinate with those officers to develop a plan for the deployment.

F. Verbal Announcement

Before deploying a canine, the handler must make a verbal announcement and repeated attempts to notify people within the area of the intent to use a canine and to afford individuals the opportunity to surrender to police. For a Direct Apprehension, the announcement should explain the consequence of not surrendering (the canine may bite the person).

G. Standard for Canine Searches and Apprehensions

This policy has specific standards for the types of canine deployments:

- Canine Searches and Apprehensions. Canines must be trained to use the “find and bark” method and handlers must use this method for Canine Searches and Canine Apprehensions. Canines must be trained to, upon locating a person, alert the handler and remain in the area until the handler arrives.

- Direct Apprehension: Any deployment of a canine to make a Direct Apprehension, (the “bite and hold” method), must be limited to the minimum amount of force the handler believes is feasible to carry out a Lawful Objective, consistent with Available Information, and must be proportional to the totality of the circumstances.

H. Residential Searches

This policy discourages Canine Searches of residences whenever circumstances present a risk of a bite to bystanders. Before conducting a search of a residence, the handler must make every effort to ensure the safety of any bystanders that might be present. Searches must be conducted on a short leash, unless the handler determines that the home contains no residents. The presence of uncontained animals in a residence will normally restrict the use of canines unless the animals can be removed or contained.

I. Prohibited and Restricted Uses

Canines must not be:

- Used solely to intimidate or coerce, or for crowd management purposes.

- Used during routine calls or arrests, or be dispatched to misdemeanor calls, unless the suspected offense falls within the list of misdemeanor offenses above.

- Used against a restrained or handcuffed person, or an individual who complies with verbal commands.

- Used during the questioning of individuals or while transporting prisoners.

- Used to search the physical body of a person for narcotics and/or contraband.

- Deployed to apprehend a fleeing person unless the conditions above for a Canine Apprehension are met.

- Used as a pain compliance technique.

- Used for purposes for which the canine is not trained and certified.

- If officers believe that a person is under the influence of drugs or alcohol or has a mental illness, canines should not be deployed unless the person poses an imminent threat to the officer or others.

1.3 – Required Medical Aid and Assistance After Canine Bite

A. Duty to Provide Medical Aid

In addition to the general duty to provide medical aid, an officer has the following specific duties when a canine bites a person:

- Releasing the canine’s bite. If a canine bites a person, the canine handler must, as rapidly as possible, determine if the person is armed and must have the canine disengage immediately upon the person being controlled or secured or otherwise complying with the officer’s commands.

- Considering reflexive responses. When determining whether the person is controlled, secured, or compliant, the handler should consider that persons confronted or apprehended by a canine will likely struggle, and struggling alone does not provide a basis for not causing the canine to disengage.

- Providing Medical Aid. Officers must immediately summon EMS and immediately provide medical aid, to the best of their skill and training whenever there has been a canine use of force or an accidental canine bite or injury.

1.4 Post-Deployment Duties, Reporting, and Investigation

A. Securing the Canine

- Securing Canine. The handler must secure the canine as soon as it becomes safe and feasible. At a minimum, the handler must secure the canine once the person has been apprehended and no longer presents a risk to the safety of the officer or others.

- Exception. Canines may remain unsecured if officers are continuing to search for other individuals, officers need the canine to search for evidence related to the suspected offense, or the canine’s presence assists in the protection of officers or others.

B. Reporting

Whenever a canine is deployed, regardless of whether a bite or injury occurs, the handler must:

- Notify their supervisor;

- Document the deployment and complete all required reports, including use of force reporting. Each canine bite or injury should be separately documented and the handler must document the duration and reason for the duration of the canine’s bite;

- Document all medical services rendered or provided;

- Attempt to locate and identify witnesses and obtain statements;

- Photograph the person who was subject to the force, including the location of any bites or other injuries, and other damage caused by the deployment of the canine.

C. Investigation and Review

Whenever a canine is deployed, the handler’s supervisor and the canine trainer must review all relevant reports, body camera footage, and photographs. The supervisor and trainer must then review these materials with the handler and provide feedback on the deployment.

1.5 – Canine Operations

A. General Operations

- The department's canine unit [or team] should maintain a manual designed to ensure that canine handlers and canines receive sufficient training, ensuring that handlers can demonstrate the necessary control over their canines’ actions.

- Supervisors of the canine unit [or team] should have significant knowledge about canine operations.

B. Requirements for Canines

All canines must complete the following requirements:

- This Department’s basic canine course or approved third-party course;

- Re-certification on a quarterly basis; and

- A minimum of 20 hours of monthly canine training.

C. Requirements for Handlers

All handlers must complete the following requirements:

- This Department’s basic canine handlers course or approved third-party course;

- Annual certification with the United States Police Canine Association or similar organization; and

- A minimum of 20 hours of monthly handler training during work hours with a Department trainer or approved third-party trainer.

Endnotes

- See National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund, "The Beginning of American K-9 Units: A Brief History."

- R. Paul McCauley et al., "The Police Canine Bite: Force, Injury, and Liability," The Center for Research in Criminology, Indiana University at 4 (2008)

- See Shontel Stewart, "Man’s Best Friend? How Dogs Have Been Used to Oppress African Americans," 25 Michigan Journal of Race & Law 183 (2020); The Marshall Project, "'A Dog Can be Trained To Be Anti-Black'," (June 23, 2021); Charlton Yingling & Tyler Parry, "The Canine Terror," Jacobin (May 19, 2016); See Tyler D. Parry, "Police Still Use Attack Dogs Against Black Americans," The Washington Post (September 2, 2020); "Review of Use of Canines by New Jersey Law Enforcement," State of New Jersey Office of the Attorney General Department of Law and Public Safety (Dec. 21, 2020).

- Abbie Vansickle, "When Police Violence is a Dog Bite," The Marshall Project (Oct. 2, 2020) (“Investigations into the police department in Ferguson, Missouri, and the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department have both found that dogs bit non-White people almost exclusively.”).

- Id.

- McCauley et al., The Police Canine Bite: Force, Injury, and Liability, supra, at 2.

- Christy E. Lopez, "Opinion: Don’t overlook one of the most brutal and unnecessary parts of policing: Police dogs," The Washington Post (July 6, 2020).

- U.S. Department of Justice Civil Rights Division and U.S. Attorney’s Office Western District of Kentucky Civil Division, "Investigation of the Louisville Metro Police Department and Louisville Metro Government" (Mar. 8, 2023).

- R.G. Dunlop, "Feds rebuke ‘excruciating’ use of police dogs in Louisville, LMPD account inconsistent," Louisville Public Media (May 16, 2023).

- Id.

- See Abbie Vansickle and Challen Stephens, "Police Use Painful Dog Bites to Make People Obey," The Marshall Project, (December 14, 2020).

- See Shaddi Abusaid, Restrained Man Bitten by Police Dog During Alpharetta Arrest, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, (July 29, 2021).

- See Matthew Slaughter, "Supreme Court's Treatment of Drug Detection Dogs Doesn't Pass the Sniff Test," 19 New Crim. L. Rev. 279, 296–300 (2016).

- Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department, “Authorized Force Tools, Description, Requirements, Uses and Considerations,” Section 6/002.02, subd. VIII.

- See S. G. Chapman, "Police Dogs Versus Crowds," 8 Journal of Police Science and Administration 316 (1980) (noting that “police are advised to know at what point dog use exacerbates rather than eases crowd problems.”).

- See Ann L. Schiavone, "K-9 Catch-22," 80 University of Pittsburgh Law Review at 636–37.

- Id. See also, Janita Peo, Billy Duryea, Mark Journey, Geoff Boucher, "Dog use to Control Crowds is Rare," (2005)(noting that “the use of trained dogs for crowd control is out of favor, some police departments say, because the poor image the practice creates, particularly in minority neighborhoods.”).

- See Shontel Stewart, Man’s Best Friend? How Dogs Have Been Used to Suppress African Americans, 25 Mich. J. Race & L. 183 (2020).

- "Review of Use of Canines by New Jersey Law Enforcement," State of New Jersey Office of the Attorney General Department of Law and Public Safety (Dec. 21, 2020).

- Vansickle, When Police Violence is a Dog Bite, supra.

- See e.g., Police Executive Research Forum, Guidance on Policies and Practice for Patrol Canines, 18 (2020) (suggesting that handler must consider all aspects of situation at hand and consider non-canine options before deciding whether to deploy a canine.).

- Office of the Attorney General, “Attorney General Becerra Calls for Broad Police Reforms and Proactive Efforts to Protect Lives,” (June 15, 2020).

- McCauley, et al., The Police Canine Bite: Force, Injury, and Liability, supra, at 27.

- Laura Haefeli, "Bark Not Bite: Department of Justice Recommends Changes to Sacramento Police K9 Tactics," CBS Sacramento (July 8, 2020).

- McCauley et al., The Police Canine Bite: Force, Injury, and Liability, supra, at 32–33.

- See "POST Law Enforcement K-9 Guidelines," California Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training at 17 (2014) (recommending “that an in-service K-9 team complete 16 hours of documented training monthly to maintain basic patrol and/or detection proficiency”).

- State of New Jersey Office of the Attorney General Department of Law and Public Safety, Review of Use of Canines by New Jersey Law Enforcement (Dec. 21, 2020).

- See Slaughter, Supreme Court's Treatment of Drug Detection Dogs Doesn't Pass the Sniff Test, supra, 19 New Crim. L. Rev. 279 at 296–97.

- Florida v. Harris, 568 U.S. 237 (2013) (holding that documentation of a drug dog’s hits and misses in detecting narcotics in the field was relevant in establishing whether an officer had probable cause under the Fourth Amendment to search a defendant’s car.)

- Id.

- See Fla. v. Harris, 568 U.S. 237 (2013); United States v. Jackson, 811 F.3d 1049, 1052 (8th Cir. 2016).

- United States v. Heald, 165 F. Supp. 3d 765, 777 (W.D. Ark. 2016) (internal quotation marks omitted).

- See e.g., Julia Sulsek, "One Bay Area City, 73 police dog bites, and the law that made them public," The Mercury News, (January 10, 2022).

- See e.g., Police Executive Research Forum, Guidance on Policies and Practice for Patrol Canines, 23 (2020) (suggesting that at a minimum agencies should record every time a canine is deployed, a canine team conducts a search, when a subject surrenders as a result of a canine being present, when a canine makes contact with a subject other than a bite, and every time a canine bites a subject).

- See e.g., Id. at 23 (suggesting that agencies should “carefully record and review all canine actions.”).