Incapacitating Weapons: Tasers and Pepper Spray

Clear and comprehensive policies on using incapacitating weapons can protect officers and community members while providing important transparency and accountability.

- Introduction

- Key things to know

- Understanding Policies on the Use of Incapacitating Weapons

- The Policy

- Endnotes

Introduction

Incapacitating Weapons: Why are policies on Tasers and pepper spray important for police and the communities they serve?

Incapacitating weapons such as Tasers and pepper spray offer police a seemingly promising solution to dangerous confrontations, potentially controlling these situations and preventing an officer from feeling that more force is needed. These tools are often seen as safer alternatives, designed to subdue individuals rather than cause serious harm. However, their use also introduces notable risks. If misused, these weapons can escalate conflicts, inflict serious injuries, and undermine community trust in law enforcement. Additionally, while not frequent, a growing number of Taser deployments have resulted in the death of a person, emphasizing the need for limiting the weapon’s use and implementing robust policies.

This module explores the complex dynamics surrounding these less-lethal tools, particularly Tasers and pepper spray. Our review of evidence-based research and leading practices suggests that clear rules and comprehensive policies can balance their utility in policing against their potential to inflict serious, or even fatal, injuries. The module underlines the importance of ensuring these tools are used only when necessary to promote community safety, build public trust, and preserve the legitimacy of the police.

Downloads

Full Model Use of Force Policy

Download the Full Model Use of Force Policy – 10 detailed policies designed to help communities implement more effective use of force policies that enhance community safety while minimizing unnecessary force.

Open Full Model Use of Force PolicyKey things to know

- Incapacitating weapons like Tasers and pepper spray provide officers with less-lethal and non-lethal force options. But Tasers are capable of inflicting deadly injuries and the use of pepper spray presents risks to individuals and other officers that must be balanced with the need to subdue a person.

- An officer may not use a Taser or pepper spray on a person that is compliant, restrained, or exhibiting only passive resistance.

- Before using an incapacitating weapon on an individual, an officer should verbally warn the person and allow time for the person to comply.

- A Taser may only be used to apply the minimum amount of force necessary. An officer is prohibited from applying the Taser, or a similar electrical weapon, for longer than a full 5-second cycle without interruption. The weapon’s full deployment should not exceed 3 cycles of 5 seconds, or 15 total seconds.

- An officer may not use an incapacitating weapon, like a Taser or pepper spray, against vulnerable categories of people, like children or the elderly, unless the particular person poses an imminent threat of serious bodily injury to themselves or others.

Understanding Policies on the Use of Incapacitating Weapons

Law enforcement increasingly uses Tasers and pepper spray to minimize fatalities and major injuries during confrontations. These 'less-lethal' alternatives to firearms are designed to cause less harm and remove the risk of fatal outcomes. However, their deployment is not without controversy or risk. Public trust in law enforcement hinges on the ethical and judicious use of force, a principle that extends to incapacitating weapons. Because these tools can lead to physical harm and sometimes even death, it is important for police departments to develop sound, evidence-based policies governing their use.

This module explores the complexities surrounding the deployment of Tasers and pepper spray, guided by key principles that prioritize human life, community and officer safety, and the minimization of unnecessary force. It scrutinizes various model policies and best practices as recommended by leading organizations like the Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) and the U.S. Department of Justice, and analyzes the varying protocols across different police departments. Particular emphasis is given to the duration and manner of deployment of these weapons, as well as the importance of considering the “totality of circumstances” before resorting to these force options.

The Model Policy aims to provide a balanced and nuanced perspective on the use of incapacitating weapons. It seeks to facilitate fair, safe, and effective policing while minimizing potential harms. By grounding these robust policies in evidence-based research, leading practices, and community input, police departments can establish new standards for responsible, adaptive policing.

Tasers and other conducted electrical weapons: tools of promise, yet not without peril

Taser adoption by law enforcement agencies rose from 40% in 2007[1] to 83% in 2011—translating to over 15,000 out of America's 18,000 law enforcement organizations.[2] Despite this widespread adoption, there is a surprising lack of uniformity when it comes to Taser-related policies. Kalfani Turè, a criminal justice scholar, has observed that these 18,000 police departments are largely operating in isolation from one another.[3]

The Model Policy's provisions emerged from an extensive review of police department guidelines, identifying policy themes that align with the overarching principle of minimizing the use of force. These themes include:

- Prioritizing human dignity and the sanctity of human life, including the safety of police officers, individuals, and bystanders;[4]

- Encouraging de-escalation;[5]

- Increasing police accountability;[6] and

- Ensuring use of lethal force is the last resort.[7]

In addition to the above themes, law enforcement perspectives reveal both challenges and opportunities in Taser deployment. One law enforcement leader highlighted an unintended consequence: "What we experienced in our department when we first started using Tasers many years ago…was a loss of verbal skills by officers…Once Tasers became prevalent, officers resorted to the use of them frequently in order to resolve situations more quickly."[8] This observation highlights the potential for Tasers to inadvertently reduce reliance on communication and de-escalation techniques.

To address such concerns, departments have implemented rigorous oversight measures. One officer pointed out the meticulous record-keeping that accompanies each Taser deployment: "With our shootings or our Taser deployments, every round is accounted for, every cycle of the Taser is accounted for."[9] Building on this accountability framework, another official stressed the obligation that follows deployment: "As soon as we deploy a Taser or a conventional weapon…the officer’s absolute duty is to go and save that individual’s life."[10]

PERF research provides additional guidance for Taser deployment, warning against overly simplistic use of force ‘continuums' that often include Tasers and rely on rigid, mechanical escalation in response to an individual’s resistance.[11] Instead, PERF advocates evaluating the 'totality of the situation' - an approach that considers real threat levels rather than rigidly sticking to a predetermined escalation of force.[12] For instance, a former Miami Police Department chief reported success in providing Tasers as an alternative to guns, particularly when dealing with the homeless population. "We went 20 months without discharging a single bullet," he concluded, emphasizing the preventive value of Tasers.[13] These varied perspectives underscore the complexity and responsibility entailed in deploying Tasers effectively and ethically.

The Model Policy’s approach to the use of Tasers

Several guiding principles anchor the Model Policy’s provisions on Tasers. A primary principle dictates that officers should always seek to communicate with a person before deploying a Taser or other conducted electrical weapon. Using minimal or no force is preferable to any weapon deployment, including less-lethal options like Tasers that can result in serious injuries.[14]

Systematic recording of Taser deployments enhances police accountability, serving as a check on the use of force. Equally important is the principle that medical attention must accompany the use of a Taser, acknowledging the health risks involved in using these weapons.

The Model Policy also recommends against relying on outdated force continuums in justifying the use of a Taser. Instead, it advocates for an approach that takes into account the totality of circumstances. This aligns with contemporary understandings of the situational factors officers face and promotes more responsible decision-making. Training and certification are mandatory because, despite their classification as less-lethal, these devices have the potential to kill.

After establishing the guiding principles and reviewing regulations from more than 100 U.S. agencies, the Boston Police Department's policy stood out in closely aligning with the Model Policy’s principles. However, there were also instances where other departments' policies more effectively reflected certain aspects of responsible Taser use. In these cases, language from those policies was either adapted or modifications were made to the Boston policy language.

While minor differences in various cities' Taser policies may not warrant extensive discussion—such as the time frame within which an officer must file a report after a Taser deployment—the analysis prioritized areas of significant policy divergence among departments. For example, the Model Policy’s section on Tasers stipulates that a firearm discharge team should submit a preliminary report to a supervising officer within five days following a Taser deployment. This contrasts with some policies, which require similar reports to be completed "in a timely fashion."

The importance of training officers to effectively use Tasers

Analysis of reviewed policies demonstrates a near-universal inclusion of a requirement for some level of Taser training. According to a PERF survey, 82% of law enforcement agencies include the training as part of their programs, highlighting the necessity of incorporating such training in the Model Policy.[15]

While the general need for training is largely uncontroversial, the specifics—training duration and frequency of refresher courses—vary among departments. Initial Taser training hours typically ranges from four to eight hours[16], with PERF's research finding recruits undergo a median of eight hours.[17] Use of force policies, however, do not always specify the required amount of Taser training.

Training delivery methods also vary among departments. Some agencies implement internal programs with the department’s officers developing and providing the instruction. On the other hand, agencies like the Boston Police Department have employed blended approaches that also include lesson plans from Axon, the Taser manufacturer. The Model Policy advocates for this multi-source method of instruction. While training materials from Axon can cover the technical dimensions of using a Taser, the manufacturer should not serve as the sole resource for a department’s training on when and how Tasers should be deployed.[18] For training on compliance with local laws, statewide police training and standards commissions are a better authority and resource. Finally, police departments are best suited to educate officers on procedures and policies specific to their agencies.

The Taser training recertification landscape has a similar amount of variability. While some departments do not mandate recertification, others require "periodic training" without specifying particular intervals. However, most departments require annual recertification, aligning with recommendations from experts. Consequently, the Model Policy also includes an annual recertification requirement.

Who should be equipped with a Taser?

The question of who should be equipped with Tasers remains a subject of significant debate among police, researchers, and civil rights advocates. Critics, including the Chief Public Defender in Pima County, Arizona, argue that Tasers can escalate rather than de-escalate confrontations.[19] In these cases, officers may resort to lethal force if the Taser proves ineffective.[20] This concern is reinforced by evaluations by several major city police departments that question Taser effectiveness in certain situations.

Research on Taser effectiveness presents a complex picture. While multiple studies indicate Tasers can reduce injuries and resolve confrontations,[21] outcomes vary across departments. Axon—the Taser manufacturer—claims that Tasers have prevented more than 250,000 instances of death or serious bodily harm.[22] However, departments' experiences show divergent results. For instance, while the Miami Police Department reported a significant drop in the use of firearms after equipping all of its officers, the Chicago Police Department found no decrease in the number of injuries caused by its officers.[23]

In response to this mixed evidence, the Model Policy opts for a measured approach: Tasers may be issued to all certified officers, but only under comprehensive protocols that require thorough training, certification, authorization, and strict accountability measures.

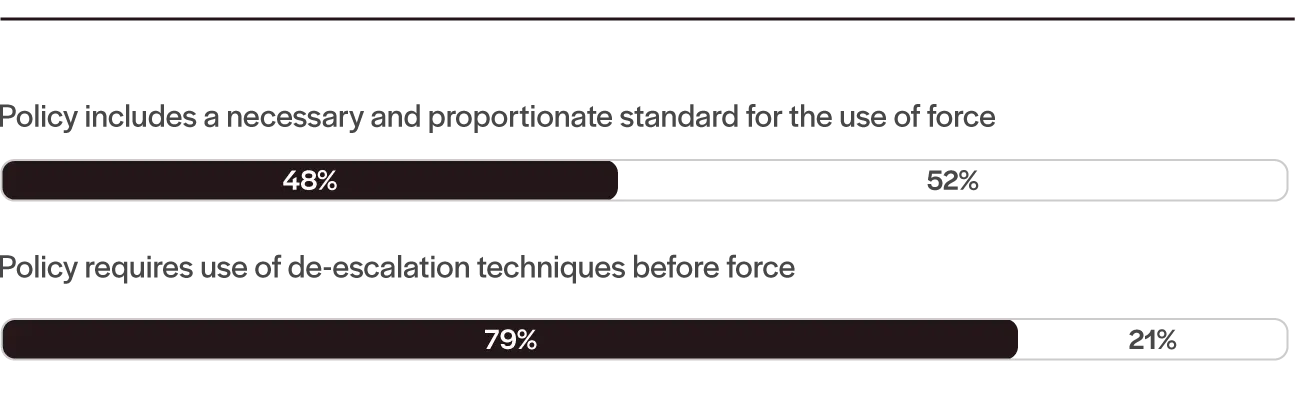

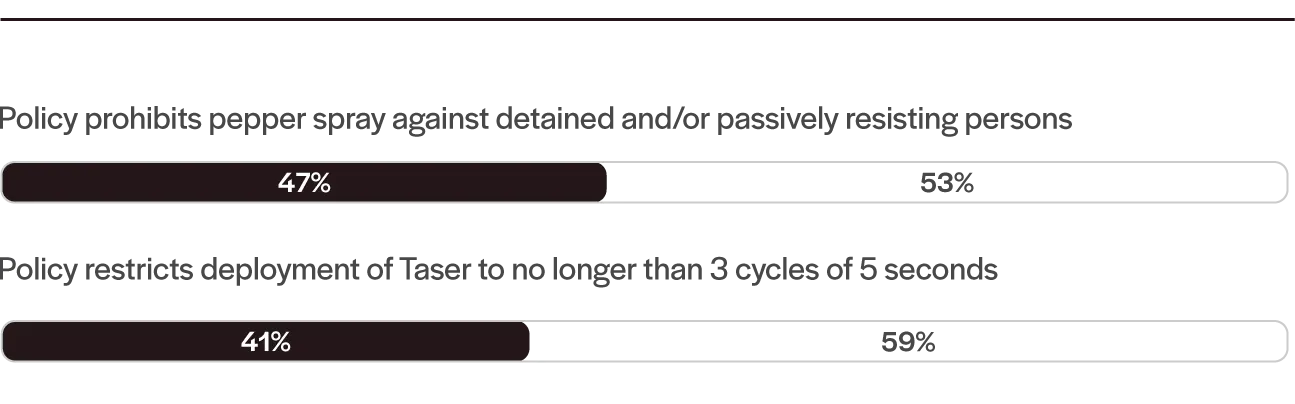

Key Force Regulations in Policies of 100 Largest U.S. Cities

Incapacitating Weapon Regulations in Policies of 100 Largest U.S. Cities

Authorizing the use of a Taser

The criteria under which officers are permitted to use Tasers differ among law enforcement agencies. One prevalent approach involves a use of force “continuum," which provides officers with a structured hierarchy of force options to deploy in different situations. A policy might stipulate that officers can use impact weapons, including Tasers, when confronting an individual armed with a knife. Alternatively, some departments advocate for a more flexible framework, encouraging officers to consider the "totality of the circumstances" when deciding whether to use a Taser. PERF argues that this approach enables a more effective and safer response that is proportional to a potential threat, arguing the rigidity of use of force continuums can inhibit creative problem-solving and de-escalation strategies. Strict continuums may inadvertently promote escalation in non-compliant situations, disregarding other variables like mental illness or an individual's age. Based on this analysis, the Model Policy requires officers to assess the entire scope of a situation, which is more likely to foster policing that respects human dignity and minimizes the use of force.

Minimizing risk through duration and cycle guidelines for Taser use

Research continues to examine how long officers should deploy a Taser to address a threatening individual. Some existing guidelines caution against using a Taser against an individual for more than 15 seconds, but there is no consensus around whether officers can, if necessary, use the Taser in one 15-second cycle or, alternatively, use the Taser in up to three cycles that do not exceed 5 seconds. Both PERF and the U.S. Department of Justice advocate for limiting each Taser deployment to no more than five seconds, given that longer exposures may heighten the risk of severe outcomes, including death. [24]

Axon contends that “current medical research in humans and animals suggests that a single exposure of less than 15 seconds from a TASER X-26 or similar model [conducted electrical weapon] is not a stress of a magnitude that separates it from the other stress-inducing components of restraint or subdual.” The Taser manufacturer also claims that “most adverse reactions and deaths associated with [conducted electrical weapon] deployment appear to be associated with multiple or prolonged discharges of the weapons.” Axon notes that extended Taser exposure may not be effective in subduing intoxicated individuals or those with mental illness, suggesting that police should consider other options in these scenarios.[25]

Based on available evidence, the Model Policy sets forth clear guidelines: officers should deploy Tasers for no more than five seconds at a time and for no more than three 5-second cycles. This approach aims to mitigate the risks associated with prolonged exposure, while still allowing for the effective use of the device.

The rising role of pepper spray in American policing

Pepper spray, commonly known by its active ingredient, oleoresin capsicum or “OC,” is an aerosolized inflammatory agent derived from the natural extract of cayenne pepper plants. Upon contact, an immediate inflammatory reaction occurs in the mucous membranes of the eyes, nose, and throat.[26] This reaction triggers symptoms such as involuntary eye closure, excessive sinus drainage, airway constriction, and temporary vocal cord paralysis.[27]

In the 1990s, law enforcement agencies widely implemented the use of pepper spray as an alternative to traditional force options, aiming to reduce instances of alleged excessive force and legal liability for officers, departments, and municipalities.[28] By 2013, approximately 94% of police departments had authorized the use of pepper spray, with a 100% adoption rate among departments in jurisdictions with populations exceeding 500,000.[29]

A review of police department policies on the use of pepper spray uncovered a degree of uniformity in the rules and procedures governing the weapon’s deployment. However, some notable variances did exist, particularly concerning training protocols and application guidelines. This module discusses these issues, along with the Model Policy’s recommended approach to pepper spray.

Some departments also possess guidelines on the use of other incapacitating chemical agents. For instance, the Tucson Police Department has had specific protocols concerning "pepperballs"—capsules filled with capsaicin powder that are expelled using compressed air.[30] The Dallas Police Department has similar guidelines.[31] Despite these examples, only a minority of departments appear to explicitly authorize the use of pepper-balls. Moreover, existing policies on this alternative are often vague and less comprehensive. Therefore, the Model Policy focuses solely on the use of pepper spray and does not extend to related weapons like pepperballs.

Strengthening department training on pepper spray

Although pepper spray is generally considered non-lethal and studies have not shown long-term detrimental effects on the eyes or respiratory system, its use still carries inherent risks.[32] These include the potential for injury to both the individual being sprayed and those in the immediate vicinity, including the officer deploying the spray. Given these risks, annual training and certification are essential for mitigating injuries and ensuring officers follow effective decontamination procedures.

A national survey on use of force training documented that police recruits receive an average of six hours of training specific to pepper spray use—significantly less than the training time allocated for other topics like de-escalation, crisis intervention, baton techniques, or Taser deployment.[33] There is also variability among police departments in the frequency and depth of pepper spray training. The Hamden, Connecticut police department requires an initial four-hour training session that covers topics such as application methods, decontamination procedures, and appropriate restraint techniques for contaminated individuals.[34] This department also mandates annual refresher training, inclusive of baton and self-defense modules.[35] Other departments only require biennial training on pepper spray. In light of these risks, including injury and cross-contamination, the Model Policy underscores the necessity for both initial and ongoing annual training.

When should officers deploy pepper spray?

Police department policies vary regarding their requirements and guidance on using pepper spray, including the duration of deployment and the recommended location of discharge. Some department protocols advise a spray duration of one or two seconds, while others recommend administering the spray in two separate half-second bursts. The International Association of Chiefs of Police ("IACP") Model Policy suggests a "single spray burst between one and three seconds."[36] Many police departments offer no specific guidance on how long the spray should be discharged.

In crafting the Model Policy’s provisions on pepper spray, these diverging protocols were weighed against the inherent limitations of and risks associated with the weapon. The aerosol form of the spray, for instance, poses challenges in accuracy, a problem that windy conditions exacerbate.[37] Pepper spray also carries a high risk of cross-contaminating other officers and bystanders.[38]

A three-second burst can be excessive for achieving the desired incapacitating effect and increases the risk of exposure to the deploying officer, their colleagues, and the public.[39] For these reasons, the Model Policy recommends a more cautious approach, specifying a spray duration of half-second bursts.

Departments also differ in their guidance on where to direct the spray. Some departments recommend avoiding direct contact with the eyes, whereas others explicitly advise officers to aim the spray "directly into the face (eyes, nose, mouth)" of the person.[40] The IACP Model Policy, too, suggests aiming the spray at the "suspect's eyes, nose, and mouth."[41] Other departments do not provide any guidance on how officers should direct their use of pepper spray.

The Model Policy advises officers to direct the spray towards the upper facial region. This approach reflects medical research that confirms the spray’s temporary inflammatory effects on the eyes and throat. To limit unnecessary harm, the policy specifically cautions against direct discharge into an individual’s eyes. While there exists a narrow distinction between recommending spraying the upper face and prohibiting a direct discharge into an individual’s eyes, given the considerable discomfort and pain induced by pepper spray, this nevertheless is important guidance for officers.

The Policy

1.1 – Key Concepts and Definitions

A. Key Concepts:

- TASER energy weapons and other conducted electrical weapons (collectively “Tasers”) and pepper spray are incapacitating weapons used by officers to interrupt a person’s threatening behavior so that officers may take physical control of the person with less risk of injury to the person or officer than that posed by more severe force options.

- Tasers are less-lethal weapons, but officers must be aware that Tasers can still inflict lethal injuries, and their use must be balanced with the need to subdue a person.

- Pepper spray is a non-lethal weapon, but its use also presents risks to officers and individuals that must be balanced with the need to subdue a person.

B. Definitions:

-

Available Information: The information that was obtainable or accessible to an officer at the time of the officer’s decision to use force. When an officer takes actions that hasten the need for force, the officer limits their ability to gather information that can lead to more accurate risk assessments, the consideration of a range of appropriate tactical options, and actions that can minimize or avoid the use of force altogether.

-

De-Escalation: Taking action or communicating verbally or nonverbally during a potential force encounter in an attempt to stabilize the situation and reduce the immediacy of the threat so that more time, options, and resources can be called upon to resolve the situation without the use of force or with a reduction in the level of force necessary.

-

Lawful Objective: Limited to one or more of the following objectives:

a) Conducting a lawful search;

b) Preventing serious damage to property;

c) Effecting a lawful arrest or detention;

d) Gaining control of a combative individual;

e) Preventing and/or terminating the commission of a crime;

f) Intervening in a suicide or self-inflicted injury; and/or

g) Defending an officer or another person from the physical acts of another.

-

Necessary: Force is necessary only if there are no other available non-force options or less-forceful options to achieve a lawful objective.

-

Reportable Force: A use of force that must be reported to the Department.

-

Resistance: Officers may face the following types of resistance to their lawful commands:

Passive Resistance: A person does not attack or attempt to attack the officer or another person, and does not attempt to flee, but fails to comply with the officer’s commands. Examples include, but may not be limited to, going limp, standing stationary and not moving following a lawful command, and/or verbally signaling their intent to avoid or prevent being taken into custody.

Active Resistance: A person moves to avoid detention or arrest but does not attack or attempt to attack the officer or another person. Examples include, but may not be limited to, attempts to leave the scene, fleeing, hiding from detection, physical resistance to being handcuffed, or pulling away from the officer’s grasp. Verbal statements, bracing, or tensing alone do not constitute Active Resistance. A person’s reaction to pain caused by an officer or purely defensive reactions to force does not constitute Active Resistance.

-

Aggression: Officers may face the following types of Aggression:

Active Aggression: A person’s attempt to attack or an actual attack on an officer or another person. Examples include, but may not be limited to, exhibiting aggressive behavior (e.g., lunging toward the officer, taking a fighting stance, striking the officer with hands, fists, kicks). Neither Passive nor Active Resistance, including fleeing, pulling away, bracing, or tensing, constitute Active Aggression.

Aggravated Aggression: A person’s actions that create an objectively reasonable perception on the part of the officer that the officer or another person is facing imminent death or serious physical injury as a result of the circumstances and/or nature of an attack. Aggravated Aggression represents the least encountered but most serious threat to the safety of officers or bystanders.

-

Totality of Circumstances: The totality of the circumstances consists of all facts and circumstances surrounding any event.

-

Verbal Command: A method of control that includes instruction or direction from an officer to an individual in the form of a verbal statement or command. The statement instructs a person to engage in or refrain from a specific action or non-action (e.g., “Put your hands behind your back”).

-

Verbal Persuasion: A method of communication to persuade, as opposed to command, a person to refrain from a specific action or non-action and to persuade a person to voluntarily comply.

1.2 – Requirements for Issuance of Tasers and Pepper Spray

A. Issuance

Tasers and pepper spray may be issued only to officers who have been trained on this Department’s use of force policies, have demonstrated the required proficiency in the use of the weapons, and become certified as trained users of the weapons, and maintain their certifications on the weapons.

B. Training and Qualification

-

All training and certification for Tasers and pepper spray must be conducted by certified instructors.

-

Training Programs. Training programs on Tasers and pepper spray must be:

a) Approved by the police chief;

b) Consistent with the manufacturer’s recommendations, as well as any laws and regulations that may be adopted relative to Tasers and pepper spray;

c) Consistent with the Department's training curriculum;

d) Consistent with the Department's use of force policy; and

e) For TASERs, adopted from the lesson plan established by the manufacturer Axon.

-

Training Courses. The courses must be approved by the supervisory officer responsible for the Department’s training section. These courses may include:

a) The Department’s training courses;

b) Manufacturer’s certification courses; and

c) Approved certification courses taught by other agencies.

-

Taser Training Frequency. Officers selected to be authorized to carry and use a Taser must receive initial and annual training that meets or exceeds the approved training standards of Axon.

-

Taser Instructor Training. Instructors must have completed the manufacturer's instructor certification program and must be certified by the state’s police officer standards and training organization.

-

Failure to Attend Annual Training. Any officer who fails to attend and satisfactorily complete annual training for Tasers shall not carry or use a Taser until completing the required course of instruction.

-

Training Monitoring/Compliance. The Department must track certification of officers to ensure there are no lapses in certification.

C. Designating a Taser Control Manager

The police chief should designate a Taser control manager. The Taser control manager must:

- Coordinate with the necessary Department leaders to ensure basic certification, annual training, and recertification training, as well as maintenance of accurate records and notification of officers whose certifications are approaching expiration;

- Receive, inspect and audit Tasers, account for their issuance to authorized personnel, and oversee maintenance of department Tasers and related equipment;

- Develop and maintain a system to comply with all state law reporting requirements and monitor the overall Taser program to ensure compliance with those requirements;

- Assist the firearm discharge investigation team [or the Department’s nearest equivalent] as requested in connection with investigations into a Taser deployment;

- Identify training needs, equipment upgrades, and recommended changes to Taser policy that should be considered as a result of the analysis.

1.3 – Storage, Testing, and Carrying of Tasers and Pepper Spray

A. Storage

Officers must treat Tasers and pepper spray as weapons. When not carried, officers must store Tasers and pepper spray securely in a manner consistent with the Department’s standards. Officers may not store pepper spray in locations where temperatures exceed 120 degrees Fahrenheit.

B. Testing and Carrying Tasers

-

Pre-shift Testing. Officers must conduct a function, or spark, test before any shift or operation during which the Taser will be carried. The test must be conducted as follows:

a) Proceed to a safe or designated area, remove the Taser from its holster, and point it in a safe direction;

b) With the safety in the down (Safe) position, press and release both Arc switches simultaneously for the Taser to display it firmware version and the battery percentage. Officers should verify that there is adequate battery capacity;

c) Shift the safety switch to the up (Armed) position

d) Press either Arc switch to perform a spark test. The Taser will arc for five seconds and the electricity arcing across the electrodes should be visible from the top or side of the Taser;

e) Shift the safety switch to the down (Safe) position.

-

Failure or Malfunction. If the Taser does not arc or otherwise function as expected, the Taser must be taken out of service and the malfunction must be reported to the appropriate supervisor.

-

Carrying. Officers must carry the Taser in an approved, Department-issued holster on the support/weak side of the body, opposite the firearm side. Officers must ensure that the Taser is properly charged and prepared for immediate use. During loading, unloading, or in any circumstance other than a deployment against a person or an authorized testing or training, officers must point the Taser in a safe direction (typically toward the ground) with the safety switch engaged.

B. Carrying Pepper Spray

- Carrying. Officers must carry pepper spray once it has been issued to them and it must be Department-approved pepper spray.

- Maintenance and Replacement. Officers must maintain and manage the replacement of pepper spray issued to them.

1.4 – Authorization and Standard for Use of Pepper Spray

A. Authorization for Pepper Spray

The use of pepper spray is authorized only when there is a Lawful Objective, lower-level force options have been ineffective or are not available, the officer issues a verbal warning before using force, and the use of pepper spray is necessary to:

- Subdue a person who exhibits Active Resistance or Aggression in a manner that is likely to result in injuries to themselves or others; or

- Incapacitate a person who poses an imminent threat of physical injury to themselves, an officer, or another person.

B. Verbal Warning Before Using Pepper Spray

If feasible and safe, the officer should provide a verbal warning and allow a reasonable amount of time for the person to comply with the warning before deploying pepper spray. A verbal warning is not required if giving the warning would compromise the safety of the officer or others.

C. Standard for Using Pepper Spray

Any use of pepper spray must be limited to the minimum amount of force the officer believes is feasible to carry out a Lawful Objective, consistent with Available Information, and must be proportional to the totality of the circumstances. In deploying pepper spray, officers must:

- Spray the pepper spray in two half-second bursts directed to the upper facial area of the person. Officers should not directly target the person’s eyes.

- Deploy the pepper spray while standing at least 3 feet from the person, except in an exigent situation, because a deployment within 3 feet increases the risk of self-contamination or contamination of others at the scene.

- Allow a brief time for the pepper spray to take effect and for the person to comply before spraying an additional burst. A second burst is authorized only if the initial burst proves ineffective in subduing the person.

- Justify each subsequent spray, after the initial application of pepper spray, as a separate application of force in the Department’s use of force reporting.

D. Avoiding Use of Pepper Spray on Vulnerable Persons

Avoiding use of pepper spray on vulnerable persons. Officers must remain aware of the greater potential for injury when using pepper spray on certain categories of people. pepper spray should not be used on the following categories of people unless they pose an imminent threat of serious bodily injury to themselves or others:

- Children;

- Elderly individuals;

- Persons believed to be pregnant

- Persons with frail health; or

- Persons with known respiratory conditions.

E. Prohibited Uses of Pepper Spray

Officers must not use pepper spray:

- Against persons who comply with the officers’ commands or exhibit only Passive Resistance;

- On persons who are handcuffed, or otherwise restrained, unless the handcuffed person continues to pose an imminent threat of physical injury, either to themselves, an officer, or another person and the person cannot be controlled by any lesser force options;

- In crowded areas, except with a supervisor’s approval after taking into account all of the circumstances, including possible pepper spray exposure for bystanders;

- To wake up a person, including an intoxicated individual;

- To threaten or draw out information from a person; and/or

- To prevent a person from swallowing narcotics.

1.5 – Authorization and Standard for Use of a Taser

A. Authorization for Taser

The use of a Taser is authorized only when there is a Lawful Objective, lower-level force options have been ineffective or are not available, the officer issues a verbal warning before using force, and the use of the Taser is necessary to:

- Subdue a person who exhibits Active Resistance or Aggression in a manner that is likely to result in injuries to themselves or others; or

- Incapacitate a person who poses an imminent threat of physical injury to themselves, an officer, or another person.

B. Verbal Warning Before Using Taser

If feasible and safe, the officer should provide a verbal warning and allow a reasonable amount of time for the person to comply with the warning before using the Taser. A verbal warning is not required if giving the warning would compromise the safety of the officer or others.

C. Standard for Using Taser

Any use of a Taser must be limited to the minimum amount of force the officer believes is feasible to carry out a Lawful Objective, consistent with Available Information, and must be proportional to the totality of the circumstances. This policy has specific standards for each of the typical Taser modes:

- Power On. Officer turns on the Taser, activating the weapon’s light and/or laser, sometimes known as the “laser and light” mode. Turning on the Taser is not, by itself, considered a use of force.

- Spark Activation. Officer depresses an arc switch activating an electric arc. This mode may be used in response to Active Resistance or Aggression.

- Drive Stun Application. Officer applies Taser directly to a person’s body as a coercive, pain compliance technique. This mode may be used in response to Active Resistance or Aggression. In this mode, the Taser does not act as an electro-muscular disruptor and drive stun capabilities—such as whether the application can be used when the Taser's cartridges have been expended—depend on the Taser model.

- Full Deployment. Officer visually and physically confirms that the weapon about to be used is a Taser and not a firearm. Officer depresses trigger, deploying primary probes at a person. A Full Deployment is comparable to an impact weapon strike and may only be used in response to Active Aggression or Aggravated Aggression.

D. Duration of Taser Deployment

A Taser may be applied for only the minimal amount of time necessary to bring the person under control. Officers are prohibited from applying the Taser for longer than a full five-second cycle without interruption. During this cycle, officers should take the opportunity to control, handcuff, or otherwise contain the person as quickly as possible.

E. Additional Applications of Taser and 15-second Maximum Limit

Additional applications of a Taser may be necessary if the person remains a threat to officers or others. Officers should be aware that a person may not be able to respond to commands during, or immediately after exposure to a Taser cycle, and should give individuals the opportunity to comply. A Taser deployment must not exceed 15 seconds (3 cycles of 5 seconds each) and the fewest number of Taser cycles should be used to accomplish the Lawful Objective.

F. Preferred Deployment Target Areas

The Taser should be aimed at a preferred deployment target area, consistent with training and manufacturer Axon’s recommendations. The Taser should not be intentionally aimed at a sensitive area, which includes the person’s face, eyes, head, throat, chest area, or groin.

G. Avoiding Use of Taser on Vulnerable Persons

Officers must remain aware of the greater potential for injury when using a Taser on certain categories of people. A Taser should not be used on the following categories of people unless they pose an imminent threat of serious bodily injury to themselves or others:

- Children

- Elderly individuals

- Persons believed to be pregnant

- Persons believed to be equipped with a pacemaker or with known or obvious serious physical health problems, including cardio-neuromuscular diseases;

- Persons in wheelchairs; or

- Persons who appear to weigh under 80 pounds.

H. Prohibited Uses of a Taser

Officers must not use a Taser in the following situations:

- When the incapacitation of the person is reasonably likely to result in death or serious bodily injury to the person or others;

- Intentionally aiming the TASER’s laser at a person’s eyes;

- On persons who are handcuffed, unless the handcuffed person continues to pose an imminent threat of physical injury, either to themselves, an officer, or another person and the person cannot be controlled by any lesser force options;

- When a person is susceptible to severe falls or is climbing or jumping to or from a fence, wall, or other elevated structure; or

- When a person is driving a motor vehicle, riding a bicycle, or adjacent to a body of water.

I. Taser as Deadly Force

Intentionally firing a Taser at a person’s head or neck is a use of lethal force and is limited to circumstances in which this policy authorizes deadly force.

J. Potential Deadly Force Situations

If an officer deploys a Taser in a situation where there is a possibility that the encounter could rapidly become a situation where the use of deadly force may be necessary, a second officer should be designated as “lethal cover” and should be appropriately armed and positioned to employ deadly force if it is necessary and authorized under this policy.

K. Use of Taser on Aggressive Animals

A Taser can be effective on aggressive or dangerous animals when necessary to protect an officer, another person, or another animal from the actions of an aggressive animal. Such use of a Taser will depend upon the circumstances and must be documented. Officers who use a Taser on an aggressive animal should consider how to control the animal as the incapacitating effect of the Taser dissipates.

1.6 – Duty to Provide Medical Aid and Assistance; Avoiding Cross Contamination and Engaging in Decontamination After Use of Pepper Spray

A. Tasers

-

Duty to Provide Aid. In addition to the general duty to provide medical aid, an officer has the following duties with respect to the use of a Taser:

a) An officer must call EMS to evaluate the subject of a full Taser deployment. Persons subjected to a Taser must be examined by EMS personnel once in custody. If the probes penetrate the skin of the person, the EMS personnel will determine if they can safely remove the probes on scene, or if the individual should be transported to a hospital for removal;

b) If the individual is transported to a hospital, the officer must obtain a medical release from the hospital before transporting the person to a detention facility. EMS personnel will be advised of the nature of the force used during the event, including the number of Taser cycles, the duration, and if more than one Taser was used or if a barb on a Taser probe may have broken with a portion remaining under the person’s skin.

-

Post-Deployment Monitoring. The post-deployment monitoring of individuals subject to a Taser application is important. Officers must request EMS assistance immediately if one or more of the following conditions exist:

- Disorientation, hallucinations/delusions, or intense paranoia;

- Violent or bizarre behavior;

- Elevated body temperature or diminished sensitivity to pain;

- An officer used a Taser on a person classified as “vulnerable;”

- Officers used more than one Taser on a person; or

- An officer exposed a person to three or more Taser cycles, or 15 seconds, or longer of continuous exposure.

-

Probe Removal. Probes may be removed after the person is restrained and secured. Officers must protect themselves and others from exposure to blood and must not attempt to remove probes from an uncooperative person. An officer must remove probes in accordance with training while taking necessary precautions for biohazards, including securing the probes in an appropriate container. Officers must not remove deeply embedded probes, or probes embedded in the head, neck, groin, or breasts of a person, or the abdomen of a person who indicates they are pregnant. EMS must be requested for removal of the probes in the above-referenced circumstances.

B. Pepper Spray

-

Duty to Provide Aid. In addition to the general duty to provide medical aid, an officer has the following duties with respect to the use of pepper spray:

a) The officer should have the person wash any contaminated areas of the skin with soap and water as soon as feasible and, at a minimum, have the affected areas of the person flushed with water within 20 minutes of the application of pepper spray. If the person wears contact lenses, the officer should instruct the person to remove them.

b) The officer must ask the person if they suffer from any respiratory diseases or problems, such as asthma, bronchitis, or emphysema.

c) The officer must monitor the person for signs of difficulty breathing, nausea, or other physical discomfort and must not leave the person unattended until the effects of the pepper spray have completely diminished, or the individual indicates they have fully recovered from the effects of the pepper spray. If the person displays respiratory problems, the officer should expose the person to fresh air, if possible, and the officer must seek medical attention immediately.

d) Under normal circumstances, the person’s symptoms should disappear within 30 to 45 minutes. If the person’s symptoms persist beyond 45 minutes, the officer must seek medical attention for the person.

-

Avoidance of Cross-Contamination and Decontamination. After resistance has ceased, the officer must inform the person that they will decontaminate the pepper spray application and that the effects of pepper spray are temporary. Officers involved in physically restraining the person should be careful not to contaminate themselves with residue from the person. Officers should keep their hands away from their faces and should wash their hands as soon as possible after contact.

1.7 – Reporting and Investigation

A. Documentation and Reporting

- When an officer deploys a Taser or uses pepper spray, the officer must report the incident to their supervisor as soon as practicable. The deploying officer and witnessing officers must complete the appropriate use of force reports.

- Officers must document in writing all incidents where they point a Taser or pepper spray at a person.

B. Evidence Collection

- Taser Probe and Cartridge Collection. Taser probes and air cartridges must be collected and submitted as evidence in accordance with Department evidence-collection, packaging, and submission policies. The probes must be handled as appropriate for a biohazard to safeguard against any contamination by bodily fluids, while preserving evidence.

- Taser Data Download. The Taser data download must be performed as soon as practicable and a report prepared by the Taser Control Manager.

- Body-Worn Camera Footage. The body-worn camera footage of each officer present at the scene at the time the Taser was deployed must be collected and submitted as evidence in accordance with Department evidence-collection, packaging, and submission policies.

C. Investigation and Disposition

- The firearm discharge investigation team must investigate any drive stun or full deployment of a Taser, other than for training purposes. The firearm discharge investigation team has sole responsibility for investigating firearm discharges involving a member of the Department.

- Where the deployment of a Taser results in death or serious bodily injury, the Department must relinquish control of the investigation to the District Attorney’s Office.

Endnotes

- Kenneth Adams & Victoria Jennison, "What We Do Not Know about Police Use of Tasers," 30 Policing: Int’l J. Police Strat. & Mgmt. 447, 448 (2007).

- Nat’l Inst. of Just., U.S. Dep’t. of Just., "Police Use of Force, Taser and Other Less-Lethal Weapons," 1 (2011) (“Taser use has increased in recent years. More than 15,000 law enforcement and military agencies use them.”); Bureau of Stat., U.S. Dep’t. of Just., National Sources of Law Enforcement Employment Data (2016) (“Law enforcement in the United States is made up of about 18,000 federal, state, county, and local agencies.”)

- Christopher Mele & Johnny Diaz, "Tasers: Are These Police Tools Effective and are They Dangerous?," N.Y. Times (June 15, 2020).

- Police Executive Research Forum, "Critical Issues in Policing Series: Guiding Principles on Use of Force,": 4 (2016) (“In order to create a shift in police culture on [minimizing the use of force], a number of departments have begun to build their use-of-force policies around statement of principle about the sanctity of all human life.”) Police Executive Research Forum at 22 (quoting Houston Executive Assistant Chief as saying “Our policies should reflect dignity and respect for all people.”); Id. at 63 (providing that recruiters should tell potential law enforcement agents that “what matters most is an unwavering commitment to the sanctity of human life, followed by your safety and our integrity.”); President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing, Dep’t of Justice, "Final Report of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing," 3 (2015) (noting that policing should reflect the protection and promotion of the dignity of all).

- Police Executive Research Forum at 106 (“We Need to Get Away from Thinking Patrol Officers Must Resolve Incidents Quickly”); Id. at 6 (noting that at least eight police departments are revamping their policies to increase de-escalation tactics); Int’l Ass’n of the Chiefs of Police, "Police Use of Force in America," 3 (2001) (“An officer shall use de-escalation techniques and other alternatives to higher levels of force consistent with his or her training wherever possible and appropriate before resorting to force and to reduce the need for force.”).

- The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, "New Era of Public Safety: A Guide to Fair, Safe, and Effective Community Policing," xiii (2019) (“Accountability is central to fair, safe, and effective policing”); NAACP Criminal Justice Department, "Pathways to Police Reform Community Mobilization Toolkit," 2 (2016) (discussing the importance of increasing police accountability as a means to decrease police killings).

- Police Executive Research Forum at 22 (“[An officer’s use of his/her] firearm should be the tool of absolute last resort.”); President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing at 15 (“Use of physical control equipment and techniques. . . should be used as a last resort.”).

- Police Executive Research Forum at 56.

- Police Executive Research Forum, "Critical Issues in Policing Series: Re-Engineering Training on Police Use of Force," (2015) at 55.

- Id. at 65.

- Police Executive Research Forum, Critical Issues in Policing Series: Guiding Principles on Use of Force at 19.

- Id.

- Police Executive Research Forum, Critical Issues in Policing Series: Re-Engineering Training on Police Use of Force at 20.

- U.S. Gov’t Accountability Office, "Taser Weapons: Use of Tasers by Selected Law Enforcement Agencies," 4 (2005); National Institute of Justice, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, "Study of Deaths Following Electro Muscular Disruption," vii (2011) (“[A] Number of individuals have died after exposure to a [conducted energy device] during law enforcement encounters. Some were normal, healthy adults; many were chemically intoxicated or had heart disease or mental illness.”)

- Police Executive Research Forum, Critical Issues in Policing Series: Re-Engineering Training on Police Use of Force at 12.

- U.S. Gov’t Accountability Office, Taser Weapons 11. This study was limited to the following law enforcement agencies: Austin Police Department, Ohio Highway Patrol, Orange County Sheriff Department, Phoenix Police Department, Sacramento Sheriff Department, Sacramento Police Department and San Jose Police Department.

- Police Executive Research Police Executive Research Forum, Critical Issues in Policing Series 10.

- Axon, "Trainers," Taser.com (last visited July 7, 2022). Axon's website featuring various trainers who teach Taser courses. It states Axon Taser trainers are “certified every two years, so you know trainers are up to date on the latest technology and safety trends” and are “subject matter experts.”

- Christopher Mele & Johnny Diaz, Tasers: Are These Police Tools Effective and are They Dangerous?, N.Y. Times (June 15, 2020).

- Curtis Gilbert, Angela Caputo & Geoff Hing, American Public Media, "Tasers are Less than Reliable," (May 9, 2019).

- See National Institute of Justice, "Police Use of Force: The Impact of Less-Lethal Weapons and Tactics," (2010) (explaining, for the Seattle Police Department, “Taser use was associated with a 48 percent decrease in the odds of suspect injury...”). Charlie Mesloh et al., "Less Lethal Weapon Effectiveness, Use of Force, and Suspect of Officer Injuries: A Five Year Analysis," 55 (2008).

- Axon, "How Taser CEWs Protect Life and Enhance Safety," (November 10, 2020).

- Bocar Ba and Jeffrey Grogger, "The Introduction of Tasers and Police Use of Force: Evidence from the Chicago Police Department," NBER Working Paper (January 2018).; Geoffrey Alpert, Michael R. Smith, Robert J. Kaminski, and Lorie Fridell, "Police use of force: Tasers and other less-lethal weapons," National Institute of Justice report (May 2011).

- Police. Executive Research Forum & Office of Cmty. Oriented Policing Servs., "Electronic Control Weapon Guidelines," 20 (2011). See National Institute of Justice, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, "Study of Deaths Following Electro Muscular Disruption," viii (2011) (“The current literature as a whole suggests that deployment of a CED has a margin of safety as great as or greater than most alternatives. Because of the physiologic effects of prolonged or repeated CED exposure are not fully understood, law enforcement officers should refrain, when possible, from continuous activations of greater than 15 seconds, as few studies have reported on longer time frames.”)

- Christopher Mele & Johnny Diaz, Tasers: Are These Police Tools Effective and are They Dangerous?, N.Y. Times (June 15, 2020). As stated by Professor Turè, a person on mind-altering drugs, such as PCP, might “walk right through it,” thus the Taser would be ineffective in subduing an individual. Id.

- Nat’l Inst. of Just., U.S. Dep’t. of Just., "Evaluation of Pepper Spray," (1997)

- Id.

- See Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs National Institute of Justice, "Oleoresin Capsicum: Pepper Spray as a Force Alternative," (March 1994).

- Nat’l Inst. of Just., U.S. Dep’t. of Just., "Pepper Spray: Research Insights on Effects and Effectiveness Have Curbed Its Appeal," (2019) (“Yet its actual use by law enforcement would wane over time with the surge in popularity of CEDs (conducted energy devices) among officers.”).

- Tucson Police Department (2001) (despite including PepperBalls as a possible use of force, the Tucson Police Department did not offer clear guidelines on their use. “PepperBalls may be fired directly at a subject, or they may be fired to strike near a subject, to deliver a more dispersed oleoresin capsicum payload. PepperBalls shall only be used to counter defensive resistance or greater.”

- Dallas Police Department General Order (2020).

- Ted M. Zollman, et al. “Clinical Effects of Oleoresin Capsicum (Pepper Spray) on the Human Cornea and Conjunctiva,” Ophthalmology, vol. 107, no. 12, Dec. 2000, pp. 2186–2189 (abstract only). Theodore C. Chan et al. “The Effect of Oleoresin Capsicum “Pepper” Spray Inhalation on Respiratory Function”, Journal of Forensic Sciences, Vol. 47 , No. 2, 2002 (abstract only).

- Police Executive Research Forum, Critical Issues in Policing Series: Guiding Principles on Use of Force (2016)

- Hamden Police Department General Orders (2015).

- Hamden Police Department General Orders (2015).

- International Association of Chiefs of Police Model Policy (Pepper Spray).

- Police Executive Research Forum, Critical Issues in Policing Series: Guiding Principles on Use of Force (2016) (noting that these shortcomings of pepper spray as an incapacitating weapon may contribute to the less frequent use of police officers in the United States than police officers in the United Kingdom, where they use PAVA (pelargonic acid vanillylamide) spray). Although there may be arguments for the use of PAVA spray to replace pepper spray, PAVA spray is not currently available in the United States).

- See Drew Scofield, "Police use Pepper Spray, K-9s to Disperse Large Crowd at Pinecrest," (June 18); Meghan Brink, "Albany Police Use Pepper Spray to Disperse Large Crowds, Fights in Pine Hills," (August 29, 2021).

- See Nat’l Inst. of Just., U.S. Dep’t. of Just., "Police Use of Force: The Impact of Less-Lethal Weapons and Tactics," (2010) (explaining that in an overall analysis on twelve agencies, it showed “for officers, however, pepper spray use increased the likelihood of injury.”)

- Philadelphia Police Department (2017).

- International Association of Chiefs of Police Model Policy (Pepper Spray)