Foot and Vehicle Pursuits

Clear and comprehensive policies on pursuits can protect officers and community members while providing important transparency and accountability.

Introduction

Pursuits: Why are policies on foot and vehicle pursuits important for police and the communities they serve?

Foot and vehicle pursuits are challenging aspects of police work, blending considerations of community safety, due process, and officer discretion. Owing to their high-stress and unpredictable nature, these scenarios often increase the likelihood that force—and more serious levels of force—will be used, underscoring the need for clear pursuit policies. This module analyzes the different dimensions of pursuit policies, spotlighting their impact on police practices and public trust.

As our research reveals, a foot or vehicle pursuit is a complex, high-risk environment. These rapidly intensifying situations carry significant potential dangers for officers, individuals, and bystanders. Consequently, this module stresses the need for solid, well-defined policies that harmonize safety, fairness, and justice. We scrutinize various policy approaches, exploring their capacity to minimize risks and constrain any potential misuse of officer discretion, especially in cases of non-violent or minor offenses. The module underscores the importance of incorporating both foot and vehicle pursuit operations into broader use of force policy conversations. It further outlines the advantages of aligning policies for these high-stakes encounters with a department’s overarching principles governing the use of force.

Downloads

Full Model Use of Force Policy

Download the Full Model Use of Force Policy – 10 detailed policies designed to help communities implement more effective use of force policies that enhance community safety while minimizing unnecessary force.

Open Full Model Use of Force PolicyKey things to know

- Foot and vehicle pursuits, while not uses of force, are dangerous for officers, individuals, and the public. An officer should avoid pursuing a person unless it is necessary and justified.

- If an officer observes a person or driver fleeing police, that alone does not justify a pursuit—additional requirements must be met.

- An officer may pursue on foot only if a person has committed an arrestable offense and the benefit of apprehending the person continues to outweigh risks to the public and the officer.

- Vehicle pursuits are prohibited unless an officer has probable cause that a person in the car committed a violent crime, it’s likely the person’s escape will seriously harm another person, the pursuit can be safely undertaken, and the officer obtains their supervisor’s approval before initiating the pursuit.

- Communication and coordination with other officers are essential for a pursuit. If an officer is unable to communicate with fellow officers, or does not receive sufficient support, the officer should not initiate a pursuit.

Understanding Policies on Pursuits

Pursuits, whether on foot or in vehicles, represent critical moments in law enforcement where interactions with the public can quickly escalate into forceful interventions. While foot pursuits do not always lead to the use of physical force, they are being increasingly acknowledged as interconnected with a police agency’s use of force policies. This linkage is highlighted by policies discouraging officers from engaging in foot pursuits that might put them at a tactical disadvantage or where an immediate apprehension is not crucial, thereby reducing the instances where force may become necessary. Likewise, vehicle pursuits, traditionally seen as separate from use of force, are now viewed as potentially lethal situations that could benefit from alignment with use of force principles.

Both foot and vehicle pursuits demand close examination within a comprehensive use of force policy framework. As an example, when the U.S. Department of Justice negotiates a consent decree with a police department over unconstitutional policing practices, modifications to policies, procedures, or training related to vehicle pursuits are often required as a part of broader use of force policy reforms. Furthermore, the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that police interventions influencing a pursuit subject's driving could constitute uses of force or seizures, which are subject to Fourth Amendment standards. Integrating foot and vehicle pursuits into use of force policymaking can yield more comprehensive and effective guidance for officers.

It is essential to acknowledge the inherent risks associated with both types of pursuits when formulating effective policies. Pursuits can present hazards to officers, individuals, and uninvolved bystanders like other drivers and pedestrians. Given the high-stakes and dynamic nature of these situations, written policies should underscore their potential risks and provide officers with clear directives. By addressing pursuits within the broader context of use of force policies, law enforcement agencies can better manage and mitigate risks, improving safety for the entire community.

Foot pursuits: balancing safety & apprehension

Foot pursuits pose risks to officers, the individuals being pursued, and bystanders, even though they are not inherently forceful.[1] A foot pursuit propels officers through a neighborhood at high speeds, leaving them uncertain about what they might encounter around each turn. Hence, officer safety—and public safety—should be the paramount consideration for a police department and its officers when deciding whether to initiate a foot pursuit and, once begun, whether to continue it.

The outcome of a chase or apprehension is always uncertain, so if an officer questions whether there is adequate justification for a pursuit, the decision should weigh against the pursuit and in favor of alternative strategies such as surveillance and containment. Recognizing these realities, the Model Policy recommends including a clear statement to that effect in a foot pursuit policy, ensuring that no officer or supervisor will face criticism or discipline for choosing not to engage in a foot pursuit, if the perceived risks to any officer or the public outweigh the potential benefits of catching the person.

Given that officers are often concerned with the risk of losing sight of an individual suspected of criminal activity, the policy recommends highlighting some of the inherent risks associated with the decision to pursue an individual on foot, thereby equipping officers with a more comprehensive understanding of how to balance those risks. For instance, the Model Policy highlights that an officer's judgment may become impaired during a pursuit due to adrenaline or fatigue.[2] Officers involved in a foot pursuit may experience distorted perception, causing them to misread an individual's sudden movements as threats, which can lead to unnecessary escalations of force with potentially lethal outcomes that could have been prevented.[3]

In recognition of the inherent dangers of foot pursuits, the Model Policy outlines preventative steps that can sometimes eliminate the need for a pursuit by reducing the chances that an individual will attempt to flee from police interaction. These strategies include maintaining a composed demeanor, engaging in constructive dialogue with the individual, and using tactical positioning to limit the individual’s avenues for escape. Based on an officer’s evaluation of the situation and the individual's response, the officer might find it beneficial to position themselves in such a way that the individual feels at an advantage, such as by sitting. Conversely, in some instances, the officer might opt to exert control over the situation through verbal or nonverbal cues.

Importance of clear rules in avoiding dangerous and unnecessary foot pursuits

Over the past decade, America's police departments have started to embrace policies that guide officers in evaluating the risks and rewards of pursuing suspects on foot. Such clear guidelines can minimize the instances of pursuits ending in lethal confrontations.[4] Many police departments, however, have not instituted policies governing foot pursuits, despite having comprehensive policies for vehicle pursuits.[5] The absence of these rules may stem from beliefs such as: a formal policy on foot pursuits is unnecessary; foot pursuits are quintessential police activities that can be addressed in training alone; or the fear that a policy might be overly restrictive in a field where officers must exercise considerable discretion. These views can overlook the significant risks associated with chasing a person on foot.

Not only have foot pursuits led to police shootings in a string of recent, high-profile incidents,[7] but various studies also reveal that a significant percentage—between 12% and 48%—of officer shootings in several U.S. cities were preceded by foot pursuits.[8] Thus, the risks are real and present a compelling case for better guidance. Formal policies on foot pursuits can equip officers with consistent, actionable principles to discern when a pursuit is warranted.

The Model Policy underlines that officers’ judgments should be shaped by the unique circumstances of a pursuit and their own policing experience. Yet, it also delineates criteria to consider and sets defined rules where the dangers of a pursuit will clearly outweigh the advantages of apprehending a fleeing person—for instance, if the person has committed a non-arrestable offense.

While some police departments have chosen to omit bright line rules, favoring officer discretion, these policies still furnish officers with a consistent set of criteria to assess pursuit dangers. Others make explicit that their foot pursuit guidelines are merely advisory, and non-compliance will not lead to disciplinary actions. Departments wary of implementing any foot pursuit policies might consider either or both of these approaches, still offering situational, environmental, and individual factors to evaluate before initiating a foot pursuit without punishing deviation from those guidelines.

Advisory guidelines that are rooted in discretion can still address some of the key issues covered by the Model Policy’s provisions on foot pursuits. Much of the peril in a pursuit arises from making rapid decisions under uncertain circumstances, possibly while physically drained or under the influence of surging adrenaline.[9] Advisory policies can expose officers to a catalog of factors they should consider in these situations, long before the officers find themselves in the position to make these decisions.[10] This proactive approach equips officers with some of the tools they need to avoid engaging in hazardous and unwarranted foot pursuits.

However, this module advocates for a non-advisory foot pursuit policy, outlining situations where pursuits are prohibited. The policy aligns with departments favoring more restrictive pursuit policies, acknowledging scenarios where the risks grossly outweigh the benefits. In these circumstances, officers should not have to deliberate whether to pursue but can act decisively on alternative methods such as coordination and containment. This clear stance underscores the critical role of definitive guidelines in avoiding unnecessary pursuits.

Authorizing and initiating a necessary foot pursuit

Policies that determine when officers are permitted to pursue individuals on foot stand as some of the most critical rules for law enforcement operations. The Model Policy explains that an officer is authorized to initiate a pursuit only when there is probable cause to believe a subject has violated a law or ordinance, or when there is reasonable suspicion sufficient to justify a Terry stop.[11] A person’s flight from police, without additional legally sufficient suspicion of the person’s criminal activity, does not alone justify initiating a pursuit.

The Model Policy also emphasizes that, even when an officer has legal justification to initiate a foot pursuit—probable cause or reasonable suspicion—a foot pursuit is only authorized when the benefit of immediately apprehending a person suspected of committing a crime outweighs the risks to public and officer safety. To help facilitate this determination, the policy includes a specific, but non-exhaustive list of practical factors that officers should consider relating to the risks of a pursuit. These factors are based on a list developed by the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) in its Model Policy for Foot Pursuits.[12]

In addition to outlining the major risks of foot pursuits, the Policy follows the IACP approach in including a list of alternatives to a foot pursuit that officers should consider before initiating a pursuit: aerial support, containment, a canine search, saturation of the area with patrol personnel, or, when enough information is available, apprehending the individual at another time and place.[13] The Model Policy also emphasizes that containment and surveillance are often the safest tactics for apprehension, and that these tactics should be used instead of foot pursuits whenever circumstances allow.

Within this framework of authorization and initiation, the policy proposes clear rules for scenarios where a foot pursuit would be inappropriate, barring extraordinary circumstances. This includes, among others, a prohibition on foot pursuits for specific classes of offenses, like those that are non-arrestable. The policy’s stance aligns with the reasoning of a growing number of police departments that, in certain situations, the minimal benefits are overshadowed by the substantial risks, rendering foot pursuits unjustifiable.[14]

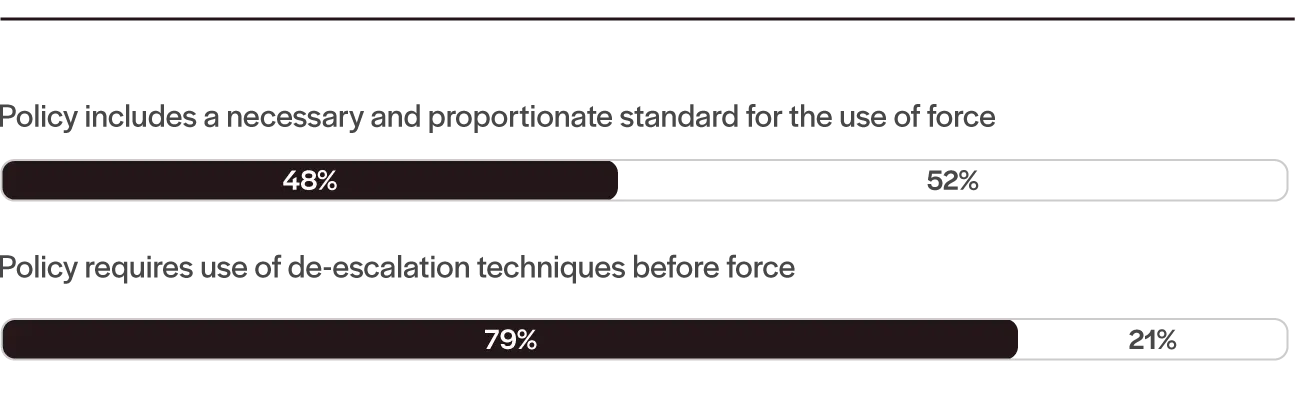

Key Force Regulations in Policies of 100 Largest U.S. Cities

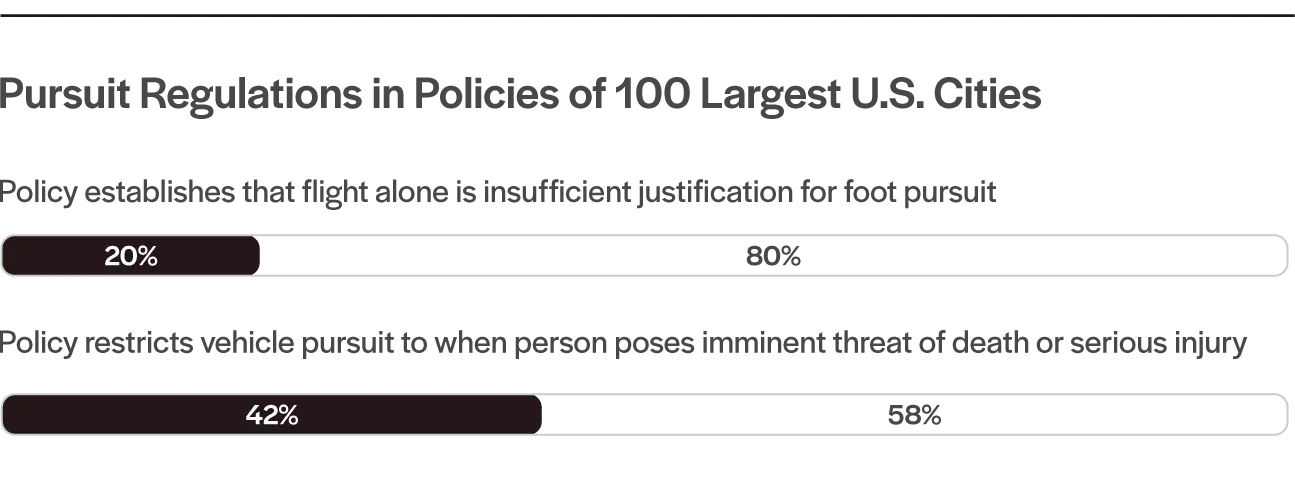

Pursuit Regulations in Policies of 100 Largest U.S. Cities

Foot pursuit policies that prioritize safety, minimize risks, and ensure accountability

Once a foot pursuit has been initiated, the situation's dynamic nature presents complex challenges and risks. Policies governing the unfolding pursuit must be carefully crafted, providing officers with guidance that both improves safety and reduces the likelihood of force being employed. The Model Policy recognizes the various factors at play, from coordination among officers to the tactical use of technology and communication.

The policy recommends that when deciding to initiate a foot pursuit, an officer immediately activate their body-worn camera. The initiating officer should ensure that their body-worn camera stays activated throughout the entire pursuit. Officers should also identify themselves and order the fleeing individual to stop. They should communicate their decision to initiate a pursuit to the department’s communications center, providing necessary details. If this information cannot be effectively communicated at the outset, the pursuit should be terminated.

Aligning with the IACP model policy and many existing department policies, the Model Policy includes detailed provisions regarding the communication systems and channels to be used throughout a foot pursuit. These details may vary by department but the underlying principle that communication is key remains constant. Another central element of the policy is the oversight of a supervisor with the authority to terminate the foot pursuit at any point. If the supervisor decides to stop the pursuit, all pursuing officers must immediately comply.[16]

When a pursuit proceeds, a primary officer should work with assisting officers to establish a perimeter around the fleeing individual. The primary officer’s goal is not to catch the person, but to keep them in sight until there is an opportunity to safely take them into custody. A supporting officer should be responsible for coordination and communication and should endeavor to stay close to and in communication with the primary officer throughout the pursuit. Importantly, the policy states that one officer should not attempt to pursue multiple individuals.

The same principles apply when two officers pursue multiple people who flee in different directions. Officers may be inclined to split up as well and to continue separate pursuits. But, under the Model Policy, it is preferable to successfully contain one of those individuals than for the officers to split and each continue a splintered pursuit on their own. Coordination is key to a successful foot pursuit, and the policy’s provisions reflect that it will be more effective for officers to engage in pursuits with support, wherever possible.

All officers should proceed with extreme caution when drawing and using firearms during a foot pursuit. The policy follows the Houston Police Department’s recommendation that firearms should be holstered while officers are running in pursuit, in most circumstances. An officer who perceives the need to unholster their firearm while running must proceed with significant caution and keep their trigger finger outside of a trigger guard unless they are justified in using deadly force and have made a conscious decision to do so.

Special considerations for pursuits involving plainclothes and undercover officers

The Model Policy recommends special considerations for plainclothes and undercover officers who become involved in foot pursuits. These officers, not being immediately recognizable as police, create risks for themselves and the public during a fast-moving pursuit. Policies should stipulate that such officers (1) alert a dispatcher of their status and clothing description, (2) follow a uniformed officer's commands during a pursuit, (3) end their participation once enough uniformed officers have joined, and (4) if in plainclothes, attempt to make themselves visible as police by wearing a raid jacket or other identifiable outer garment.

When to end a foot pursuit

Pursuits present unique challenges to law enforcement, requiring that officers continually assess whether to proceed with the operation or make the difficult decision to end it, even when an apprehension appears within reach. The Model Policy emphasizes an officer's responsibility to terminate a foot pursuit if instructed by a supervisor, and stresses the need for ongoing evaluation of changing conditions. It directs both pursuing officers and supervisors to consider specific factors that may weigh in favor of terminating the pursuit, except when there is an immediate threat to the safety of others.

Those factors, discussed in more detail in the policy, suggest that terminating a pursuit should be considered as fatigue sets in, as tactical advantages are lost, if the need for immediate apprehension diminishes, or if the environment becomes less conducive to an effective pursuit and apprehension.

Independent of these factors, the policy notes that a pursuit must stop when the danger of continuing the pursuit outweighs the need for immediately apprehending the person. A clear statement should be included that the supervisor is responsible for the decision to terminate as soon as it appears that the pursuit is no longer justified, both legally and factually. For example, termination must occur if another suspect is apprehended elsewhere, nullifying the reasonable suspicion for the pursued individual.

When a pursuit is terminated, whether because the fleeing person was apprehended or based on a decision to stop pursuing, the primary officer should notify the coordinating communications center of their location and what assistance, if any, is needed. The supervisor should then travel to the location to support and control the situation as needed.

Vehicle pursuits: a restrictive approach for safety

Unlike foot pursuits, police departments are likely to address vehicle pursuits in a policy separate from the department’s use of force policy. But vehicle pursuits are intrinsically tied to the concept of force. Motor vehicles can cause lethal harm and car chases rarely end without a show or use of force by officers.[17] For these reasons, aligning vehicle pursuit policies with the principles in use of force policies can be essential.[18]

The U.S. Department of Justice has acknowledged this when intervening to address unconstitutional policing practices, sometimes requiring an agency to revise its vehicle pursuit policies during a reform of broader use of force policies.[19] Moreover, the Supreme Court has recognized that police interventions affecting pursuit subjects' driving can constitute uses of force or seizures that are subject to the requirements of the Fourth Amendment.[20]

Even where officers never make contact with the subject of a pursuit, a vehicle pursuit itself poses risks to the involved officers, the occupants of the vehicle being pursued, and uninvolved third parties, including other drivers, pedestrians, and bystanders.[21] Because vehicle pursuits present dangers to all these persons—and are likely to be undertaken in fast-developing situations where an officer is motivated to apprehend a fleeing person—it is important for department policies to make clear that vehicle pursuits pose considerable risks and provide clear guidance to officers in making decisions under these circumstances.[22]

The Model Policy encourages a restrictive approach, rather than one that elevates discretionary decision-making by line officers and supervisors. It states that in specific circumstances, the unavoidable dangers of a vehicle pursuit may overshadow any potential benefits. The policy thereby prohibits vehicle pursuits except where the pursued vehicle is occupied by a person who is suspected of committing a crime of violence and who poses an ongoing, imminent threat of death or serious bodily harm to others if not apprehended. Recognizing that this rule represents a significant shift from many current practices, this module explains the reasoning for this important decision.[23]

Why restrictive approaches towards vehicle pursuits are gaining traction

A 2019 report issued by the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights explained that, at a minimum, pursuit policies should set “clear parameters dictating when officers may initiate a vehicle pursuit.”[24] A version of this recommendation was advanced in the early 1990s, by a group of researchers associated with the U.S. Department of Justice’s National Institute of Justice.[25] Those researchers, who studied a sample of “restrictive” police pursuit policies in existence at the time,[26] concluded that a police pursuit policy should “[s]tat[e] the rules for initiating a high-speed pursuit,” “[n]am[e] the types of offenses for which high-speed pursuit is allowed or not allowed,” and “[e]xplicitly describe[e] tactics that may or may not be used” in a pursuit.[27]

During the same period, IACP adopted a model policy that preserved discretion over whether to pursue a fleeing vehicle for officers on the ground.[28] That IACP model policy provided officers with a set of criteria to consider, but did not impose any absolute restrictions on the situations in which officers could undertake pursuits.[29] The revised version of the IACP model policy adopted in 2015 added more criteria, but maintained the same approach of encouraging officers to consider various logistical and environmental conditions, without articulating bright line rules about when pursuits would or would not be permitted.[30]

By 2013, research suggested nearly 80% of sworn law enforcement officers in the U.S. worked under vehicle pursuit policies that imposed some restrictive criteria and the percentage of officers who worked in agencies that left pursuit decisions entirely to officers’ discretion had declined.[31] These more restrictive criteria started to have an impact. During 2012–2013, officers at police agencies that imposed restrictive pursuit criteria engaged in fewer pursuits when compared to officers at agencies that left pursuit decisions up to line officers’ discretion.[32]

Yet even as police departments imposed restrictions on officer discretion, the number of vehicle pursuits rose overall from 1990 to 2013.[33] A study of the IACP’s pursuit database during a similar time period found that more than 40% of pursuits were initiated in response to a fleeing driver who had committed traffic violations, as opposed to a more serious or dangerous offense. An additional 18% of pursuits were initiated because the vehicle was believed to be stolen, a serious offense but an offense that does not present an ongoing risk of harm to the public.[34]

The harm caused by vehicle pursuits themselves can be significant: vehicle pursuits can result in serious bodily injury or death, most frequently of uninvolved drivers or pedestrians.[35] And the risk of harm resulting from a vehicle pursuit is not distributed equally: a study of vehicle pursuits in 2013 and 2014 found that Black drivers were more likely to be pursued than white drivers, that deadly pursuits of Black drivers were more likely to begin over a minor or nonviolent offense, and that Black individuals—whether involved in a vehicle pursuit or not—were killed at a disproportionate rate as the result of police pursuits.[36]

Recently, some police departments have recognized that their discretionary vehicle pursuit policies permit chases in situations where the risks of the pursuit are unjustified, when compared with the risk posed by the fleeing vehicle. These departments have revised their pursuit policies. The Atlanta Police Department instituted a “no-chase” policy in 2020 following an incident where officers pursued suspects in a stolen vehicle and the pursued vehicle crashed into a third car, killing two people.[37] Atlanta Police Chief Erika Shields acknowledged “this will not be a popular decision” and that it might “drive crime up”; however, she identified other factors that rendered the risk of harm to officers and other members of the public far too severe to justify the benefits of vehicle pursuits.[38] However, Atlanta ended its moratorium on vehicle pursuits at the end of 2020 and now permits its officers to undertake pursuits but only when an occupant of the pursued vehicle has committed or attempted to commit one of an enumerated list of forcible felonies.[39]

The Model Policy’s restrictive approach to vehicle pursuits

The Model Policy adopts a restrictive approach to vehicle pursuits. This approach is influenced in large part by vehicle pursuit policies developed in New Orleans and Seattle, as well as the strategy employed by the Atlanta Police Department in 2021 after its one-year moratorium on pursuits.[40] Because vehicle pursuits present acute risks to officers, fleeing individuals, and bystanders alike, the policy contends that these risks are not often justified by the potential benefit of apprehending a fleeing person, except when the person has committed or attempted a violent felony that makes the suspect a continuing danger to the community. The policy does not permit vehicle pursuits for the sole purpose of protecting property, or when the evading person does not pose an imminent threat of death or serious bodily injury to others.

Police departments may need to adjust elements of their pursuit policies to account for their patrol environments.[41] For example, officers undertaking vehicle pursuits in densely populated and highly trafficked urban environments will likely consider different risk factors than officers who patrol less dense suburban or rural environments. The policy requires officers to consider their general surroundings when conducting pursuits, but the environment becomes especially relevant when an officer considers whether and when it is safe to undertake a pursuit intervention tactic.

The Model Policy also follows the approach of restrictive pursuit policies in determining that certain intervention tactics—including fixed roadblocks, ramming, and discharging firearms to stop a moving vehicle—are categorically prohibited. However, other interventions, which still pose risks to officers, fleeing individuals, and bystanders, may be undertaken by properly trained officers who have received authorization from the pursuit’s supervisor, when the fleeing vehicle presents risks that outweigh the risks of the intervention tactic. This provision is intended to cover the use of interventions like stop sticks and the “precision immobilization technique,” or “PIT” maneuver—a pursuit tactic involving using a pursuing police car to cause the fleeing car to turn sideways, lose control and stop.[42] But the Policy leaves the questions of whether and when officers will be trained to use these interventions to individual agencies. Even permitted intervention tactics present serious risks to pursuit participants and the public, and PIT maneuvers, in particular, have been responsible for deaths and serious bodily injuries.[43] While some evidence suggests that PIT maneuvers may be undertaken safely in limited circumstances, and may remain a viable option for ending a pursuit where the officer has sufficient training and knowledge and the risk is justified, high-profile examples of deadly PIT maneuvers show that further research is needed on this tactic, including how and when it can be deployed safely.[44]

Another key difference among law enforcement agencies concerns the availability of supporting technology to aid in a pursuit or even make it unnecessary. The policy acknowledges that certain tools, such as air support or GPS tagging devices, may be out of reach for some agencies due to size and funding constraints. Consequently, the policy does not rely on these resources as consistent aids in pursuits. Yet, when such technology is accessible, research indicates that these alternatives can enhance the safety of a pursuit or aid officers in locating and apprehending people who have evaded capture.[45]

The Policy

1.1 – Key Concepts and Definitions

A. Key Concepts:

- Foot and vehicle pursuits are not themselves uses of force but may involve the use of force, including intervention tactics and the apprehension of a person following a pursuit.

- Pursuits present substantial dangers to officers and members of the public, require strong justification, and must be conducted in accordance with this policy.

B. Definitions:

- Crime of Violence: A felony offense involving the infliction of death or serious bodily injury, or the threat of death or serious bodily injury.

- Fleeing: A driver’s act of increasing speed, taking evasive actions, or refusing to stop after a reasonable time, after an officer’s use of voice, lights, or sirens to signal to that driver to stop. A vehicle driven by a fleeing driver is a Fleeing Vehicle.

- Vehicle Pursuit: An active attempt by an officer in an authorized emergency vehicle to apprehend a person that is fleeing in a motor vehicle and attempting to flee from the officer.

1.2 – Preventing Foot Pursuits

A. Prevention

This Department prioritizes preventing the need for officers to engage in foot pursuits. Officers should utilize the following strategies:

- Officers should take precautions when approaching individuals who are suspected of having committed offenses, to discourage and prevent individuals from fleeing on foot.

- Officers can use tactical positioning to block potential escape routes and should be aware of the angle of their approach.

- Officers can use their body language to affect an encounter—for example, to assert control over a situation or allow a person to feel comfortable in the situation, based on the officer’s judgment of what will be most effective.

- Officers should maintain a calm demeanor and speak calmly to engage a person in a dialogue.

B. Alternatives to a Foot Pursuit

Officers should consider the following alternative strategies:

- Containment of the area;

- Saturate the area with patrol personnel;

- Canine search;

- Aerial surveillance;

- Apprehension at another time and place if the person’s identity is known or the officer has information that will likely allow such an apprehension.

Even if a foot pursuit is legally justified, containment and surveillance strategies are often the safest tactics officers can use to apprehend a person, and officers should use those strategies instead of a foot pursuit, when the circumstances allow.

1.3 – Authorization and Standard for Foot Pursuit

A. Authorization for Foot Pursuit

A foot pursuit is authorized only when:

- Pursuing the person is legally justified because the officer has probable cause to believe that the person has violated a law or ordinance, or the officer has reasonable, explainable suspicion that would meet the requirements for a Terry stop; and

- The benefit of immediately apprehending the person suspected of committing the offense outweighs the risks to public and officer safety.

B. Mere Flight Alone Insufficient for Pursuit

Officers may not undertake a foot pursuit based only on the observation that a person is avoiding a police presence or fleeing police. People may avoid contact with a police officer for reasons that do not indicate criminal activity.

C. Risk Considerations for a Foot Pursuit

In deciding whether to initiate or continue a foot pursuit, officers should consider the following risk factors that may make a pursuit more dangerous and less likely to end in a successful apprehension:

- Whether the officer is operating alone;

- Whether the officer is unfamiliar with the area;

- Whether the surroundings are challenging or confrontational;

- Whether the individual being pursued is known or suspected to be armed;

- Whether the officer will be able to maintain communications and obtain backup support in a timely manner;

- Whether the officer is physically able to pursue and successfully apprehend the person; and

- Inclement weather, darkness, or other reduced visibility conditions.

D. Standard for Conducting a Foot Pursuit

Upon deciding to initiate a foot pursuit, an officer must:

- Identify themselves as a police officer and order the fleeing individual to stop.

- Communicate with dispatch that they have initiated a foot pursuit. The officer should communicate: the officer’s call-sign/identifier, the officer’s location and direction, the reason for the foot pursuit, and any information known about the person being pursued.

E. Limit on Number of Pursued Individuals

Except in exigent circumstances, an officer operating alone may not pursue multiple individuals.

F. Use of Firearms During a Foot Pursuit

An officer must have their firearm holstered while running under most circumstances. If this policy authorizes the officer to unholster their firearm, they must proceed with extreme caution while running with an unholstered firearm. The officer must re-holster their firearm before physically restraining a person.

G. Involvement of Plainclothes and Undercover Officers

The involvement of plainclothes and undercover officers in a foot pursuit can pose special risks to officers and the public, as it may not be possible to immediately recognize these officers as police. Plainclothes officers must endeavor to make themselves readily recognizable as police officers by wearing an outer garment like a raid jacket as well as their official police identification.

H. Prohibited Foot Pursuits

Officers are prohibited from engaging in foot pursuits if the suspected criminal activity is a citation-only offense or non-arrestable offense.

1.4 Termination of a Foot Pursuit

A. Order to End Pursuit

An officer must terminate a foot pursuit if directed to do so by their supervisor, at any time.

B. Continuous Reassessment of the Benefits/Risks of Pursuit

Officers must continually reassess whether the benefits of a foot pursuit outweigh the risks under the circumstances. If an officer is unable to determine whether the benefits of the pursuit outweigh the risks, the officer may not undertake the pursuit and must instead use alternative strategies.

C. Legal Justification Expires

If the legal justification for the foot pursuit ceases, the pursuit must end. For example, if a person apprehended elsewhere is identified as the perpetrator of the offense, the person being pursued should no longer be considered a suspect.

1.5 – Authorization and Standard for Vehicle Pursuit

A. Authorization for Vehicle Pursuit

An officer may engage in a Vehicle Pursuit of a Fleeing Vehicle only when:

- The officer determines that probable cause exists that a person in the Fleeing Vehicle has committed or attempted to commit a Crime of Violence;

- The person’s escape would pose an imminent threat of death or serious bodily injury to others;

- The Vehicle Pursuit can be safely undertaken based on the factors set forth in this policy; and

- The officer receives supervisory approval before initiating the Vehicle Pursuit.

B. Supervisory Approval Required

Upon determining that the conditions authorizing a Vehicle Pursuit are met, the officer must promptly provide a supervisor with the circumstances surrounding the proposed Vehicle Pursuit. The supervisor who responds to the officer’s call is responsible for determining whether a Vehicle Pursuit is justified and should be initiated. If the officer proposing to undertake a Vehicle Pursuit does not receive a response, the officer must not undertake the pursuit.

C. Risk Considerations for a Vehicle Pursuit

In deciding whether to initiate or continue a vehicle pursuit, officers should consider the following risk factors that may make a pursuit more dangerous and less likely to end in a successful apprehension:

- Risk of the Fleeing person’s conduct towards others;

- Information known about the Fleeing person;

- Physical location and road configuration, weather and environmental conditions, existence of vehicle and pedestrian traffic, and lighting and visibility;

- Relative performance capabilities of the officer’s vehicle and the Fleeing Vehicle;

- Officer’s training and experience; and

- Presence of other persons in the officer’s vehicle or the Fleeing Vehicle.

D. Standard for Conducting a Vehicle Pursuit

Upon deciding to initiate a Vehicle Pursuit, an officer must:

- Communicate with dispatch that they have initiated a vehicle pursuit. The officer must communicate: the officer’s call-sign/identifier, the officer’s location and direction, the reason for the vehicle pursuit, a description of the Fleeing Vehicle and its occupants, the current speed of the pursuit, and traffic conditions.

The officer—the primary pursuit unit—and any other pursuit units directly involved in the Vehicle Pursuit must:

- Activate lights and sirens. All pursuit units must activate emergency lights and sirens which must remain activated for the duration of the pursuit.

- Drive with caution. All pursuit units must drive with caution, traveling at a reasonable and prudent speed and maintaining control of their vehicles. Units may not proceed through intersections with red lights, stop signs, or yield signs, without first ensuring that it is safe to continue through the intersection.

- Maintain a safe distance. All pursuit units must maintain a safe distance from the Fleeing Vehicle and other vehicles so that they preserve visibility, avoid hazards, and can react to maneuvers by the Fleeing Vehicle.

- Relay information to dispatch. The pursuit units should relay information to dispatch, including developments on the direction and location of the pursuit.

- Limit the number of pursuit units. No more than three vehicles may be directly involved in a Vehicle Pursuit of one Fleeing Vehicle.

The supervisor managing the Vehicle Pursuit must:

- Monitor and oversee the pursuit. The supervisor is responsible for monitoring the pursuit’s progress and overseeing the pursuit, including monitoring radio transmissions, and proceeding in the direction of the pursuit’s progress in non-emergency mode.

- Terminate the pursuit if necessary. The supervisor must direct that the pursuit be terminated at any point when the supervisor determines that the risks of continuing the pursuit outweigh the benefits of immediate apprehension of the vehicle, or when the supervisor learns any information that causes the pursuit to no longer be justified.

Uninvolved units in the field should:

- Monitor the progress of the pursuit. Uninvolved units should monitor the progress of the pursuit and may position themselves at intersections along the route of the pursuit to warn drivers and manage traffic.

- Refrain from following the pursuit. Uninvolved units are prohibited from following the pursuit on parallel roadways or driving in emergency mode.

1.6 – Termination of a Vehicle Pursuit

A. Continuous Reassessment of the Benefits/Risks of Pursuit

The primary pursuit unit and the supervisor managing the pursuit must continually reassess whether the benefits of the Vehicle Pursuit outweigh the risks under the circumstances. These officers must terminate the pursuit whenever the risks of continuing the pursuit are no longer justified based on Available Information.

B. Circumstances when Pursuit Must be Terminated

An officer must terminate a Vehicle Pursuit when:

- The supervisor managing the pursuit directs that the pursuit be terminated.

- The conditions in this policy authorizing the pursuit are no longer met.

- The primary pursuit unit loses visual contact with the Fleeing Vehicle for fifteen seconds and the vehicle’s location is no longer definitively known.

1.7 – Authorization for Vehicle Pursuit Intervention Tactics

A. Authorization for Vehicle Pursuit Intervention Tactics

The use of intervention tactics is authorized only when:

- An officer believes, consistent with Available Information, that the continued movement of the Fleeing Vehicle would place others in imminent threat of death or serious bodily injury;

- The risk of harm from the Fleeing Vehicle, if it continues to flee, is so great as to outweigh the risk of harm involved in forcibly stopping the vehicle; and

- The officer receives supervisory approval to use intervention tactics.

B. Prohibited Intervention Tactics

The following intervention tactics are prohibited:

- Fixed roadblocks;

- Moving or rolling roadblocks;

- Ramming a vehicle;

- Forcing Fleeing Vehicles off the road, including through boxing in; and

- Discharging a firearm to stop a Fleeing Vehicle.

1.8 – Vehicle Pursuits Crossing Jurisdictions

A. Vehicle Pursuits that Continue into Other Jurisdictions

When a Vehicle Pursuit extends into another jurisdiction, the managing supervisor must determine if the other jurisdiction should be asked to assume the pursuit. A Vehicle Pursuit into a bordering jurisdiction must comply with the regulations of both jurisdictions and any applicable agreements between the jurisdictions. An officer’s actions will continue to be governed by the policies of this Department.

B. Vehicle Pursuits from Other Jurisdictions

When requested to join a Vehicle Pursuit that will continue from a neighboring jurisdiction into this Department’s jurisdiction, a supervisor must determine whether the Vehicle Pursuit should be assumed by this Department and direct units accordingly.

1.9 – Reporting Requirements for Foot and Vehicle Pursuits

A. Documenting Pursuit

After a pursuit has terminated, the officer who initiated the pursuit must complete an incident report documenting the pursuit. Reports should include the following details: date and time of the pursuit, reason for the pursuit, distance and path of the pursuit, alleged offenses of the person who was pursued, the results of the pursuit, and any injuries or property damage that occurred as a result of the pursuit. All other officers involved in a Vehicle Pursuit should complete their own supplemental incident reports and, for a foot pursuit, supporting officers should supplement the pursuing officer's incident report as needed.

B. Reporting Use of Force

If the pursuit involved any use of force, including a pursuit intervention that involved the use of force on a pursued vehicle, any officer using force must complete a use of force report.

Endnotes

- See, e.g., Nirej Sekhon, Blue on Black: An Empirical Assessment of Police Shootings, 54 Am. Crim. L. Rev. 189, 191, 207 (2017) (more than half of officer-involved shootings in Chicago over the study period occurred during foot chases); Robert J. Kaminski, Jeff Rojek & Mikaela Cooney, "Police Foot Pursuits: Report on Findings From a National Survey on Policies, Practices and Training," Univ. of S.C. Dept. of Criminology and Crim. Just., 1, 2 (2012) (48% of officer-involved shootings in Philadelphia between 1998 and 2003 “involved foot pursuits”).

- New Era of Public Safety: A Guide to Fair, Safe, and Effective Community Policing 127-28 (2019).

- Id.; see also Police Exec. Research Forum, "Critical Issues in Policing Series: Re-Engineering Training," (2015), at 22-23 (statement of Dallas Assistant Chief Tom Lawrence) (discussing how foot pursuits have ended in shootings that were justified in the moment but which prompted a review of “how we got there”); id. at 23 (statement of Dallas Assistant Chief Charles Cato) (explaining that during a foot pursuit, “[p]hysiological changes happen in your body. Your heart rate increases, your respiratory rate increases, you lose your fine motor skills, the fight-or-flight syndrome kicks in, and it can affect your cognitive ability.”).

- See Police Exec. Research Forum, Re-Engineering Training, supra note 3, at 19, 22-23, 55; see also Jonathan Hogan, "Recent Incidents Raise Questions About Foot Pursuits," Idaho Falls Post Register (July 26, 2019); Molly Sullivan & Anita Chabria, "After Stephon Clark Shooting, Sacramento Police Create New Policy for Chasing Suspects," Sacramento Bee (Aug. 13, 2018).

- See, e.g., Megan Cassidy, "Phoenix Police Rethinking Traditional Foot Pursuits," AZCentral (Oct. 11, 2015); see also Robert J. Kaminski & Jeff Rojek, "Police Foot-Pursuit Policies, Practices and Training: Findings from a National Survey," (Aug. 10, 2015) (unpublished manuscript), (surveying large law enforcement agencies in the U.S. and concluding that the majority do not have a written foot pursuit policy, despite rising concerns regarding risk and safety).

- See id.; see also Police Exec. Research Forum, Re-Engineering Training, supra note 3, at 23 (statement of Dallas Assistant Chief Tom Lawrence (“This is something new; I was never trained in foot pursuits. It was just, ‘Run as hard as you can, and whoever is faster will win.’”)).

- See Hogan, supra note 4; Sullivan & Chabria, supra note 4; see also Patrick Smith, "Chicago’s Release of Police Shooting Videos May Change Foot Pursuit Policy," NPR (Apr. 30, 2021) (detailing two high-profile, pursuit-related police shoot-ings that led to the enactment of Chicago’s first foot pursuit policy); J. Garrity Jr., "Establishing a Foot Pursuit Policy: Running into Danger," 69 FBI L. Enforcement Bull. 10, 10-11 (2000) (observing that many department fail to adopt foot pursuit policies because pursuit is “a basic function of law enforcement” and officers fail to recognize the risk).

- See Robert J. Kaminski & Jeff Rojek, Police Foot-Pursuit Policies, Practices and Training: Findings from a National Survey 3 (Aug. 10, 2015).

- See Police Exec. Research Forum, Re-Engineering Training, supra note 2, at 23 (statement of Dallas Assistant Chief Charles Cato) (discussing the “[p]hysiological changes” that occur during a pursuit).

- See id. (statement of Dallas Assistant Chief Charles Cato) (explaining that “[i]n a stimulus- response situation” like a foot pursuit, “we want you to do the thinking before you get to that point”)

- See New Era of Public Safety, supra note 2, at 127 (“Many factors may motivate an innocent person to flee”).

- Int’l Ass’n of Chiefs of Police, "Model Policy: Foot Pursuits," at 1-2 (listing risk factors that officers should consider when initiating or continuing a foot pursuit).

- Id. at 1.

- On the utility of rules that “[i]dentify what activities police should and should not be engaging in,” see Statement of Ronald L. Davis, Chair, Legislative Committee, Nat’l Organization of Black Law Enforcement Execs., Before the H. Comm. on the Judiciary Hearing on Policing Practices and Law Enforcement Accountability 10 (June 10, 2020). See also id. (recommending that this process of identifying appropriate police functions be undertaken in “[c]ollaboration with the community”).

- Int’l Ass’n of Chiefs of Police, Model Policy: Foot Pursuits at 2.

- Id. at 2.

- See generally Geoffrey P. Alpert & Patrick R. Anderson, The Most Deadly Force: Police Pursuits, 3 Just. Q. 1, 3 (1986); see also Richard R. Johnson, A Longitudinal Examination of Officer Deaths from Vehicle Pursuits, 15 Int'l J. Police Sci. & Mgmt. 77, 78–79 (2013) (“Approximately 1 in 100 pursuits results in a fatality, with more than one third of these fatalities being uninvolved third parties or police officers.”) (citation omitted).

- See Am. Law Inst., Principles of the Law, Policing: Revised Tentative Draft No. 1, at 21 (draft policy) (July 30, 2017) (noting that use of force matrices “may or may not acknowledge that different rules are required in specific contexts, such as . . . vehicle pursuits,” and recommending that use of force “policies should move beyond” the current, “limited concept of proportionality reflected in existing tools to take account of these varied factors”).

- Police Exec. Research Forum, "Civil Rights Investigations of Local Police: Lessons Learned," 13 (2013).

- See Brower v. Cty. of Inyo, 489 U.S. 593, 599 (1989); see also Scott v. Harris, 550 U.S. 372, 381 (2007) (noting that an officer’s “decision to terminate the car chase by ramming his bumper into respondent’s vehicle constituted a ‘seizure’”).

- See Hugh Nugent, Edward F. Connors III, J. Thomas McEwen & Lou Mayo, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, NCJ 122025, Nat’l Inst. of Justice, "Restrictive Policies for High-Speed Police Pursuits," 23 (date unknown) (“High-speed vehicle pursuits are possibly the most dangerous of all ordinary police activities.”); New Era of Public Safety, supra note 2, at 125 (collecting statistics on the numbers of passengers and bystanders injured or killed by police vehicle pursuits).

- See Alpert & Anderson, supra note 17, at 3.

- See, e.g., New York State Municipal Police Training Council, Use of Force Model Policy (Sept. 2020) (making no mention of vehicle pursuits); Sample Policy Manual, Texas Police Chiefs Association (same).

- New Era of Public Safety, supra note 2, at 127.

- Nugent et al., supra note 21, at 18.

- The researchers defined “restrictive” policies as those that “plac[e] certain restrictions on officers’ judgments and decisions,” as opposed to policies allowing officers to exercise discretion on “all major decisions” or policies “cautioning against or discouraging any pursuit, except in the most extreme circumstances.” Id. at 2.

- Id. at 18-19.

- See Cynthia Lum & George Fachner, Int’l Ass’n of Chiefs of Police, "Police Pursuits in an Age of Innovation and Reform: The IACP Police Pursuit Database," (2007), at app. A (Vehicular Pursuit Model Policy (1996)).

- See id.

- Int’l Ass’n of Chiefs of Police, Model Policy: Vehicular Pursuit 1-2 (2015).

- Brian A. Reaves, Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, NCJ 250545, Police Vehicle Pursuits, 2012-2013, at 5 (2017).

- Id. at 6.

- Thomas Frank, "High-Speed Police Chases Have Killed Thousands of Innocent Bystanders," USA Today (July 30, 2015); see also id. (observing that the data on deaths resulting from police pursuits collected by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration likely undercounted these figures based on different jurisdictions’ reporting requirements, and that no national data on injuries is collected).

- Lum & Fachner, supra note 28, at 56; see id. (noting that the three most prevalent reasons for initiating a pursuit—traffic offenses, belief that the vehicle was stolen, and belief that the driver was intoxicated— accounted for more than seventy-five percent of pursuits during the study period).

- See Frank, supra note 33 (noting that more than half of the people killed in the course of police vehicle pursuits from 1979 to 2013 were bystanders and passengers); see also Lum & Fachner, supra note 28, at 57 (finding that 9% of police pursuits reported in the IACP’s pursuit database ended in injury, and that nearly 20% of those pursuits ended in serious or fatal, as opposed to minor, injuries).

- Thomas Frank, "Black People Are Three Times Likelier to Be Killed in Police Chases," USA Today (Dec. 1, 2016).

- See Tyisha Fernandes, "2 Dead After Driver Running from Police Crashes at Atlanta Intersection," WSB-TV (Dec. 5, 2019); Matt Johnson, "Atlanta Police Begins No-Chase Policy Effective Immediately," WSB-TV (Jan. 3, 2020). The pursuit was permitted under the policy in effect at the time in Atlanta, which a deputy chief described as “very strict” but which permitted a pursuit in this case of a “vehicle . . . taken at gunpoint.” Id.

- Johnson, supra note 37.

- Asia Simone Burns, "Atlanta Police Alter ‘No-Chase’ Policy," Atlanta Journal-Constitution (Jan. 4, 2021); see also Atlanta Police Dep’t, Policy Manual, Standard Operating Procedure 3050: Pursuit Policy 2-3 (2020).

- See Seattle Police Dep’t, Police Department Manual, 13.031: Vehicle Eluding/Pursuits (2021) (“Officers will not engage in a vehicle pursuit without probable cause to believe a person in the vehicle has committed a violent offense or a sex offense” and “probable cause to believe that the person poses a significant imminent threat of death or serious physical injury to others”); New Orleans Police Dep’t, Operations Manual, Chapter 41.5: Vehicle Pursuits (2019) (“Upon express supervisory approval, officers are authorized to initiate a pursuit only when . . . an officer can articulate that a suspect is attempting to evade arrest or detention for a crime of violence . . .; . . . the escape of the subject would pose an imminent danger of death or serious bodily injury to the officer or to another person; and . . . the suspect is fleeing in a vehicle after having been given a signal to stop . . .”); see also New Era of Public Safety, supra note 2, at 127 (citing the Seattle vehicle pursuit policy with apparent approval as an example of “provid[ing] clear parameters dictating when officers may initiate a vehicle pursuit”); Jonathan Aronie & Geoff Alpert, "16 to a Dealer’s 10: Could Blackjack Odds Help Inform Police Pursuit Policies?," Police1 by Lexipol (Mar. 2, 2020) (discussing the New Orleans Police Department’s vehicle pursuit policy).

- See New Era of Public Safety, supra note 2, at 125 (observing that “[h]igh-speed police car chases are inherently dangerous, especially in urban areas and on densely populated streets” (emphasis added)).

- Shaun Raviv & John Sullivan, "Deadly Force Behind the Wheel," Washington Post (Aug. 24, 2020) (noting that PIT interventions resulted in at least thirty deaths and hundreds of injuries nationwide, during the period 2016-2020).

- See id.

- See Schultz, Hudak & Alpert, "Emergency Driving and Pursuits: The Officers' Perspective," (April 2009) (reviewing evidence from across jurisdictions and finding that “the PIT can be effective and efficient when used properly,” though “[i]n many other cases, it is more appropriate for the officer in a pursuit to turn off his lights and siren and stop or turn around”); see also Raviv & Sullivan, supra note 42 (noting that 74 of 142 responding agencies did not permit use of the PIT maneuver under any circumstances); Madison Police Dep’t, Standard Operating Procedure: Emergency Vehicle Operation Guidelines 6 (2020) (defining PIT as a “ramming technique[]” and per-mitting its use only where deadly force would be justified).

- See, e.g., Morgan Gaither et al., "Pursuit Technology Impact Assessment: Final Report Version 1.1," at 34 (January 2017) (concluding that the GPS-deployment system StarChase, “when properly deployed, had a positive impact on the pursuit outcome for apprehensions” (footnote omitted)); Geoffrey P. Alpert, "Helicopters in Pursuit Operations," Nat’l Inst. of Justice: Research in Action, Aug. 1998, at 1, 3 (finding that pursuits undertaken with the assistance of helicopters “compare[d] favorably” to pursuits involving ground units alone); see also Albuquerque Police Dep’t, Procedural Orders, SOP 2- 45: Pursuit by Motor Vehicle 7 (2020) (providing that “[o]nce air sup-port has responded and has a visual on the pursued vehicle, the Air Support Unit shall be the primary unit of the authorized pursuit…Pursuing unit(s) willstop the motor vehicle pursuit and provide enough distance so as not to affect the driving of the pursued vehicle.”).