Firearms and Other Deadly Force

Clear and comprehensive policies on using firearms and other deadly force can protect officers and community members while providing important transparency and accountability.

- Introduction

- Key things to know

- Understanding Policies on the Use of Firearms and Other Deadly Force

- The Policy

- Endnotes

Introduction

Deadly weapons: Why are policies on using firearms and other deadly force important for police and the communities they serve?

When an officer draws their firearm, it amplifies the potential for a situation to escalate and significantly raises the stakes for police, the people they are engaging, and community members. For many, firearms are the embodiment of deadly force whether held at an officer’s side, pointed at an individual, or fired. The gravity and permanence of outcomes involving these weapons—as well as other deadly force like an intentional baton strike to the head—underscores the need for precise rules, detailed training, and a comprehensive approach to de-escalating situations.

Our research into leading practices suggests that there is a set of effective firearm policies that better safeguard human life and preserve the public’s trust in law enforcement. This module establishes that firearms can only be used as a last resort and focuses extensively on the de-escalation strategies that police should integrate into their policies and training on firearms. Because firearms are the most common deadly force weapon, the module further explains how departments should set an appropriately strict standard for their use: when all other non-deadly options have been exhausted and absolute necessity requires it to protect the safety of an officer or another person.

Downloads

Policy on Firearms and Other Deadly Force

Download the model policy on Firearms and Other Deadly Force.

Download PolicyFull Model Use of Force Policy

Download the Full Model Use of Force Policy – 10 detailed policies designed to help communities implement more effective use of force policies that enhance community safety while minimizing unnecessary force.

Open Full Model Use of Force PolicyKey things to know

- Deadly force is force that poses a substantial risk of causing death or serious bodily injury to a person. It is the most serious force that an officer can use.

- The use of a firearm—whether unholstering, pointing, or firing—is deadly force and must be viewed as an option of last resort that an officer should avoid wherever possible.

- Unnecessarily or prematurely drawing a firearm poses deadly risks, including unjustified or unintentional firing of the weapon. Drawing a firearm can limit an officer’s options to control a situation or create unnecessary anxiety for a person.

- Before using a firearm, all available non-deadly force options must have been attempted, an officer must issue a verbal warning, and the officer must determine that using the firearm is necessary for the safety of the officer or another person.

- An officer may not: fire a warning shot, draw or fire against a person who poses a threat only to themselves, or use the firearm solely to defend property. Using a firearm against a fleeing person or from a moving vehicle is also prohibited, except in very limited circumstances.

Understanding Policies on the Use of Firearms and Other Deadly Force

When an officer unholsters their firearm and considers using it to stop a person, they are faced with the most serious and consequential choice in policing. Decisions about when to use deadly force are almost always complex, time-sensitive, and clouded by stress, fear, and uncertainty about an individual’s intentions. For these reasons, police departments need effective and precise policies on using firearms and deadly force as well as a comprehensive approach to de-escalating situations that removes individuals, officers, and other community members from dangerous situations.

The Model Policy’s goals of making policing safer, fairer, and more equitable for everyone inform the policy’s approach to the use of firearms and other deadly force. Under the policy, firearms are the last decision point an officer can reach once all other non-deadly options have been exhausted and absolute necessity requires their use to protect the safety of an officer or another person. This strict standard, which is only met when an officer or another person faces an imminent threat of death or serious bodily injury, better safeguards human life and preserves the public’s trust in law enforcement. Further, the policy’s extensive focus on de-escalation strategies and rigorous training underscores how a department’s full complement of policy tools can be used to effectively limit the use of deadly force.

Key deadly force principles

It is important that policymakers and the policies they develop recognize the difficulty of police officers’ work, while also acknowledging the seriousness of the use of firearms and other deadly force. Policy language can acknowledge that: (1) the duties of an officer may require the use of deadly force in some instances, (2) the use of deadly force constitutes the most serious act an officer can engage in during the course of their duties, (3) the department values the protection of human life and dignity, (4) the safety of the public must be the overriding concern when officers consider the use of deadly force, including the use of firearms, (5) the authority to carry and use firearms in the course of public service carries with it an immense power, which comes with great responsibility, and (6) the use of deadly force, including the use of a firearm, must be limited to being an option of last resort, which officers should avoid whenever possible.

This type of “expectation setting” language respects officers by acknowledging the difficult, multifaceted, and highly scrutinized aspects of their work. It also recognizes the unusual power that officers wield over others in society—including the ability to legally shoot and kill a person. The above policy language also conveys the seriousness of using deadly force and states clearly that deadly force should be avoided when possible. These recommendations follow the growing number of police departments across the U.S. that now include language in their use of force policies encouraging de-escalation and requiring the use of alternatives before using deadly force.

Many departments, however, still do not include this type of introductory language in their policies. While departments commonly set forth general provisions on when deadly force should be used, and how its use will be assessed, many do not emphasize that deadly force should be used only when necessary as a last resort. Use of force policies that forego this type of language may not appropriately convey the seriousness of using deadly force, and that could lead to the use of deadly force in situations that do not require it.

A number of departments also include introductory language noting that the department values human life as well as the dignity of individuals. The inclusion of language referencing dignity, in addition to human life, conveys that people, including those suspected of committing serious crimes, should be afforded an appropriate measure of civility and respect in a nation of laws. It reminds officers that the use of force, especially deadly force, harms an individual’s dignity and curtails their freedom, even when legally justified.

Some departments have stated within their firearms and deadly force regulations that, as a matter of policy, they value property. While this sentiment is likely shared by most in society, expressing it near an acknowledgment of the value of human life can unintentionally imply that the department values life and property equally. This, in turn, could lead officers to errantly assume that they may and should use deadly force to protect property.

Restricting deadly force: de-escalation strategies, verbal warnings, and explicit limitations

The Model Policy recommends several provisions that limit the use of deadly force—especially firearms—while recognizing that officers may face rare situations requiring the use of this force. De-escalation strategies, which are the focus of a separate policy module, should be incorporated as a principle underlying all use of force policies, including the use of deadly force. For example, the Model Policy requires the integration of de-escalation training into firearms training and the exhaustion of available non-deadly force options as a step in justifying the drawing and use of a firearm.

As part of a comprehensive de-escalation approach, the policy also includes a provision requiring officers to issue an appropriate verbal warning to an individual, their fellow officers, and bystanders before discharging a firearm, when practicable. The officer issuing the warning should identify themselves as a police officer, clearly give the command they want followed, and state their intention to shoot if the person does not comply with the command.

The policy makes clear that an officer should wait a reasonable amount of time after the warning before discharging the firearm, to allow an individual to comply with the warning. Along with the warning, when an officer points a firearm at a person, the officer should advise the person of the reason why the officer has pointed the firearm. Many police policies do not contain specific provisions regarding these types of verbal warnings. The effective use of warnings are a form of de-escalation that can make unnecessary uses of deadly force less common.

Additionally, the Model Policy recommends that officers draw and discharge firearms only in situations where the use of deadly force is authorized. Policies should explain that pointing a firearm at a person qualifies as a seizure under the Fourth Amendment that requires legal justification, and that an officer should not point a firearm at or in the direction of a person unless the officer has a reasonable perception of a substantial risk that the situation may escalate to justify deadly force.

Policies should also disallow officers from drawing or discharging a firearm for the sole purpose of defending property, including evidence, because these interests are not equal to a loss of life. Furthermore, the Model Policy follows most departments in including a provision prohibiting officers from discharging a firearm as a warning.

Unnecessarily holding a firearm poses deadly risks, including an unwarranted or unintentional discharge of the firearm.[1] When an officer unnecessarily holds their firearm, it may also limit the officer’s tactical alternatives in controlling a situation or create unhelpful anxiety on the part of the individual or public.[2] For these reasons, when the situation renders the use of deadly force no longer absolutely necessary, an officer must secure or re-holster their firearm as soon as practicable.

The Model Policy also prohibits officers from intentionally displaying or drawing a firearm in any manner other than for proper inspection or official use in compliance with a department’s policy. Policies should note that a person gaining control of one or more pieces of an officer’s equipment does not, without more, justify the use of deadly force, unless the person takes additional action that satisfies the threshold for deadly force. Together these policies convey the seriousness of the use of deadly force and reinforce the notion that deadly force should be used only when necessary.

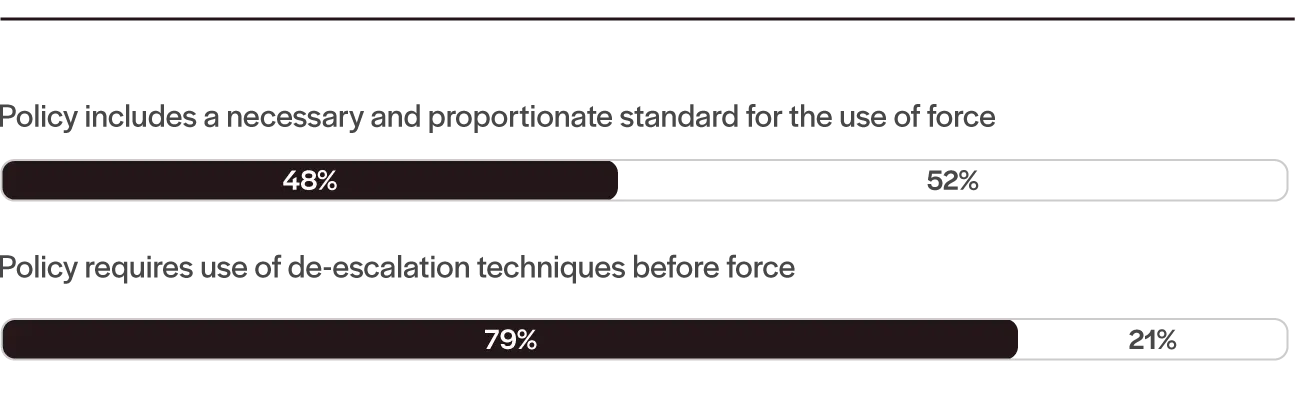

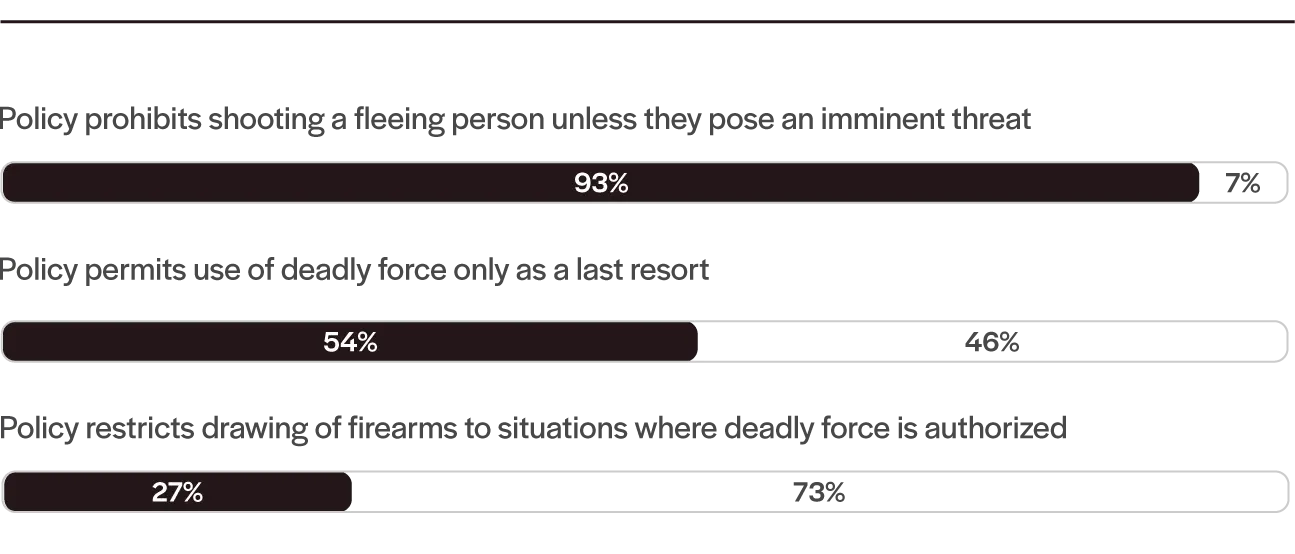

Key Force Regulations in Policies of 100 Largest U.S. Cities

Deadly Force Regulations in Policies of 100 Largest U.S. Cities

Authorization and standard for the use of deadly force

Policies covering the use of deadly force should have clear rules and standards on when the highest level of force is authorized. The Model Policy states that deadly force may be used only when available non-deadly force options have been exhausted and absolute necessity requires the use of deadly force to protect the safety of the officer or another person. Deadly force, when used, must be necessary and proportionate to address the situation presented.

This standard is higher than some police department policies, which permit the use of deadly force when an officer has a “reasonable” belief that a situation requires the use of deadly force.[3] These departments require their officers’ decisions to be “objectively reasonable” given the totality of the circumstances at the time of an officer’s action, the minimum standard for an officer’s use of force under the U.S. Constitution.[4] In strengthening the standard for the use of force, the Model Policy is prioritizing the sanctity of life and determining that the grave implications of using firearms and other deadly force warrant a higher standard.

Special policy considerations involving deadly force

There are several special policy considerations for the use of deadly force. First, most police department policies address the challenging situation of moving vehicles and fleeing suspects. Consistent with many of these department policies, the Model Policy recommends that policies should prohibit officers from discharging a firearm at or from a moving vehicle, except under certain restricted, specific exceptions and prohibit officers from discharging a firearm at a fleeing person unless the person presents an imminent threat of death or serious bodily injury to members of the public.

Most police department use of force policies, however, do not address the use of deadly force to prevent suicide or self-harm. There, the Model Policy advances an approach that bans officers from using deadly force against a person who presents only a danger to themselves. More specifically, officers may not use firearms in an attempt to prevent a suicide, unless the person poses an imminent threat of death or serious bodily injury to the officer or another person.

Many use of force policies are similarly silent regarding the use of deadly force against dangerous or critically injured animals. The Model Policy addresses those issues because officers frequently encounter pets and other animals in the line of duty and benefit from firm guidance in these situations.[5] The inclusion of these provisions can also decrease the frequency of unnecessary or unjustified killings of animals by police.

In situations where officers foresee that they will encounter a dangerous animal, some policies require that officers plan ahead, as much as possible, by developing a contingency plan. This is thoughtful guidance and a contingency plan could involve making sure that officers have non-lethal weapons or tools available to subdue or control a dangerous animal on the scene, or request that local animal control officers be present on the scene. Further, the policy provides that officers may use deadly force against a dangerous animal when the situation meets the requirements for deadly force, and may use deadly force to euthanize a critically injured animal when the officer does not have alternative methods reasonably available. Some federal circuits have held that shooting a dog may constitute a seizure under the Fourth Amendment,[6] and, if an officer makes the decision that an animal must be killed, the officer must make every effort to ensure that they discharge their weapon safely and humanely to prevent the animal from undue suffering or escape, and in compliance with policy.[7]

The importance of requiring firearms training

Despite the importance of firearms training, many use of force policies do not include language specifying the training that officers must complete and the standards they must meet to be allowed to carry firearms in the line of duty. The Model Policy conveys that the use of firearms is a privilege, not a right, and that an officer’s training obligations are ongoing. To carry and use authorized firearms, officers must first demonstrate proficiency in the use of firearms, complete in-service training regarding the use of firearms (on an annual basis),[8] and certify that they will follow the department’s use of force policy, before being issued an authorized firearm. Additionally, officers who fail to qualify or re-qualify on firearms must successfully complete remedial training before engaging in official law enforcement duties that require the use of firearms.

Firearms training should include de-escalation techniques, in addition to ensuring that officers are qualified to carry and use firearms safely and accurately. To reinforce that training, the Model Policy recommends that officers’ firearms qualification tests include being evaluated on de-escalation skills and the ability to recognize situations where alternatives to force are appropriate.[9]

Documenting, reporting, and providing medical assistance for deadly force incidents

Departments should include specific policies on documenting and reporting deadly force incidents, as well as providing immediate medical assistance in connection with those incidents. While many police department policies feature these provisions, some do not. For instance, the Model Policy requires officers to document, in writing, all incidents where they point a firearm at a person and all incidents where they witness or receive a report that another officer pointed a firearm at a person.[10] Officers should also be required to document all incidents where they unholster a firearm, with exceptions only for administrative and incidental unholstering due to activities like routine maintenance, target practice, and undressing.

Whenever an officer discharges a firearm in the line of duty, the officer who discharged the firearm and other officers who witnessed the incident must be required to immediately notify the 911 dispatcher, regardless of whether or not the discharge resulted in death or injury. Further, when an officer discharges any firearm (with the exception of legal recreation or training purposes), whether on-duty or off-duty and regardless of the type of firearm, the officer and any other officer who witnesses the incident should immediately report the incident to their supervisor.[11]

All discharges of department-issued firearms or other firearms discharged in the line of duty—whether intentional or unintentional—should be investigated and reviewed and the Model Policy underscores this approach.[12]

The Policy

1.1 – Key Concepts and Definitions

A. Key Concepts:

- Deadly force is a force that poses a substantial risk of causing death or serious bodily injury. Deadly force includes, but is not limited to, using a firearm or an intentional strike to the head with a baton or other impact weapon.

- Under this policy, deadly force is an option of last resort, which officers must avoid whenever possible. Above all the Department values the protection of human life and the safety of the public must be the overriding concern in an officer’s decision whether to use deadly force, including the drawing and discharging of a firearm in response to an imminent threat of death or serious bodily injury.

B. Definitions:

-

Available Information: The information that was obtainable or accessible to an officer at the time of the officer’s decision to use force. When an officer takes actions that hasten the need for force, the officer limits their ability to gather information that can lead to more accurate risk assessments, the consideration of a range of appropriate tactical options, and actions that can minimize or avoid the use of force altogether.

-

De-Escalation: Taking action or communicating verbally or nonverbally during a potential force encounter in an attempt to stabilize the situation and reduce the immediacy of the threat so that more time, options, and resources can be called upon to resolve the situation without the use of force or with a reduction in the level of force necessary.

-

Lawful Objective: Limited to one or more of the following objectives:

a) Conducting a lawful search;

b) Preventing serious damage to property;

c) Effecting a lawful arrest or detention;

d) Gaining control of a combative individual;

e) Preventing and/or terminating the commission of a crime;

f) Intervening in a suicide or self-inflicted injury; and/or

g) Defending an officer or another person from the physical acts of another.

-

Necessary: Force is necessary only if there are no other available non-force options or less-forceful options to achieve a lawful objective.

-

Proportional: Proportionality in the use of force goes beyond necessity. Even if the use of force is necessary to achieve the Lawful oObjective, it must also match the threat posed to the officer or public.

-

Totality of Circumstances: The totality of the circumstances consists of all facts and circumstances surrounding any event.

1.2 – Requirements for Issuing, Storing, and Carrying a Firearm

A. Issuing a Firearm

-

Certification. To be issued a Department firearm, an officer must be certified as a trained firearm user. This Policy limits certification to personnel who successfully complete the Department’s authorized training course and demonstrate the required proficiency in the use of a firearm.

-

Officer Acknowledgement. Officers also must certify in writing that they have read, understood, and will abide by the Department’s use of force policy, before being issued a Department firearm.

-

Training. Officers must participate in and complete initial Department-approved training on the use of firearms and at least annual in-service training. All training and certifying for firearms must be conducted by certified instructors. Training on firearms must be:

- Approved by the police chief;

- Consistent with the manufacturer’s recommendations, as well as any laws and regulations that may be adopted relative to firearms;

- Consistent with the Department’s training curriculum; and

- Consistent with the Department’s use of force policy.

-

Proficiency. Officers must demonstrate firearm proficiency in the following ways:

- Achieve minimum qualifying scores on a prescribed course or test, on at least an annual basis;

- Attain and demonstrate knowledge of the laws on the use of authorized weapons and knowledge of Department policy on the use of force, de-escalation of force, crisis intervention, and deadly force;

- Be familiar with safe handling procedures for firearms and other weapons; and

- Demonstrate proficiency in de-escalation techniques.

-

Failure to Re-Qualify. Any officer who fails to qualify or re-qualify for issuance of a firearm may not carry or use a firearm. The officer must complete remedial training and demonstrate proficiency in the use of firearms to resume official law enforcement duties that require the carrying or use of firearms. Personnel trained in the use of firearms will be held accountable for proficiency and training in compliance with Department policy and state law.

-

Training Monitoring/Compliance. The Department must track certification of officers to ensure there are no lapses in certification.

-

Designating a Firearm Control Manager. The police chief should designate a firearm control manager. The firearm control manager must:

- Coordinate with the necessary Department leaders to ensure basic certification, annual training, and recertification training, as well as maintenance of accurate records and notification of officers whose certifications are approaching expiration;

- Receive, inspect and audit firearms, account for their issuance to authorized personnel, and oversee maintenance of Department firearms and related equipment;

- Develop and maintain a system to comply with all state law reporting requirements and monitor the overall firearm program to ensure compliance with those requirements;

- Assist the firearm discharge investigation team [or the Department’s nearest equivalent] as requested in connection with investigations into a firearm discharge; and

- Identify training needs, equipment upgrades, and recommended changes to the firearm policy that should be considered as a result of the analysis.

B. Carrying a Firearm

- Department-Approved Firearms. Officers may carry and use only those firearms, holsters, ammunition, and accessories provided and authorized by the Department, except in exigent circumstances.

- Safety Precautions. Officers must take reasonable safety precautions when carrying, transporting, handling, loading, or unloading any firearm.

C. Storing a Firearm

When not carried, officers must store firearms securely in a manner consistent with the Department’s standards.

1.3 – Authorization and Standard for Use of a Firearm or Other Deadly Force

A. Authorization to Use Deadly Force

The use of deadly force is authorized only when all the requirements to use force are satisfied and both of the following additional circumstances exist:

-

All available non-deadly force options have been exhausted; and

-

The use of deadly force is absolutely necessary:

- To protect an officer or another person from imminent death or serious bodily harm that is more likely than not to occur without the use of deadly force, provided that the officer can specifically articulate the observable circumstances that led the officer to conclude that the use of deadly force is necessary, and the officer’s belief is consistent with Available Information; or

- To effect the arrest of an individual who the officer has probable cause to believe has committed a felony that caused or threatened to cause death or serious bodily harm; and the officer believes that the individual is more likely than not to cause death or serious bodily harm to an officer or another person unless immediately apprehended and the officer’s belief is consistent with Available Information.

B. Duration of Authorization to Use Deadly Force

The authorization to use deadly force lasts only as long as the threat supporting the authorization. When the situation makes the use of deadly force no longer absolutely necessary, the officer must secure or re-holster their firearm as soon as practicable.

C. Drawing a Firearm

An officer may not draw or exhibit a firearm unless the circumstances create reasonable cause for the officer to believe the firearm’s use is authorized under this policy.

D. Pointing of a Firearm

The pointing of a firearm at or in the direction of another person constitutes a seizure that requires a legal justification. An officer may not point a firearm at or in the direction of a person unless that officer has a reasonable belief that the use of deadly force is authorized under this policy.

E. Standard for Using Firearm or Other Deadly Force

The use of a firearm or other deadly force must be absolutely necessary to carry out a Lawful Objective in the belief of the officer and consistent with Available Information. This use of a firearm or other deadly force must be proportional to the totality of the circumstances where an imminent threat of death or serious bodily injury to the officer or another person exists.

F. Specific Verbal Warnings for Firearms

- Warning if Pointing Firearm. An officer who points a firearm at a person must verbally advise the person of the reason why they pointed the firearm.

- Warning Before Discharge. An officer must issue a verbal warning to the person, other officers, and bystanders before discharging a firearm. The officer should identify themselves as a police officer, clearly issue the Verbal Command they want followed, and state their intention to shoot if the person does not comply with the command. The officer should wait a reasonable amount of time, if possible, to allow the person to comply with the warning before discharging the firearm.

- Exception. This policy does not require a verbal warning if giving the warning would not be possible or would result in a risk of death or serious bodily injury to the officer or another person.

G. Avoiding Conduct that Increases Risk of Deadly Confrontation

Officers must be aware that they can escalate situations to where they feel that deadly force is necessary. An officer’s conduct before a confrontation must not increase the risk of a deadly confrontation. The Department will consider the following factors in determining whether an officer’s conduct increased the risk of a deadly confrontation:

- Whether the officer missed opportunities to de-escalate;

- Whether the presence of officers escalated what was initially a minor/non-threatening situation and eliminated the opportunity for de-escalation; and

- Whether the officer genuinely and reasonably believed deadly force was necessary given the officer’s conduct before the confrontation.

H. Prohibited Uses of Firearms

The following uses of firearms are prohibited:

- Intentionally displaying or drawing a firearm in any manner, except for official use in compliance with this policy or for an inspection.

- Discharging a firearm as a warning.

- Drawing or discharging a firearm against an individual who poses a threat only to themselves, such as in an attempt to prevent a suicide.

- Drawing or discharging a firearm at a fleeing person unless the person poses an imminent threat of death or serious bodily injury to another person.

- Drawing or discharging a firearm for the sole purpose of defending property, including evidence.

- A person gaining control of one or more pieces of an officer’s equipment does not, without more, justify the use of deadly force, unless the person takes additional action that justifies the use of deadly force under this policy.

I. Restriction on Discharging Firearms at or from Moving Vehicles

- Restriction on Discharging Firearms at or from Moving Vehicles. An officer may not discharge a firearm at or from a moving vehicle, except when an imminent threat of death or serious bodily injury to the officer or another person exists. For example, this exception may apply if the driver or passenger discharges a firearm from the moving vehicle at the officer. However, being in the path of a moving vehicle cannot be the sole reason for discharging a firearm at the vehicle.

- Avoiding Path of Moving Vehicle. An officer must not place themselves in the path of a vehicle where the need to use deadly force is the likely outcome and must make every effort to move to a position of safety rather than discharging a firearm at the vehicle or any occupant.

J. Use of Firearm as an Impact Weapon

An officer may not use a firearm as an impact weapon except when a person attempts to take the firearm from the officer, or the situation justifies the use of deadly force under this policy.

K. Use of Firearm or Other Deadly Force on Aggressive Animals

An officer may use a firearm or other deadly force against a dangerous animal when this policy authorizes the use of deadly force. An officer may also use a firearm or other deadly force to euthanize a critically injured animal when the officer does not have alternative methods reasonably available.

1.4 Required Medical Aid and Assistance After Use of a Firearm

In addition to the general duty to provide medical aid, an officer has the following specific duties when an officer discharges a firearm:

- Immediately notify 911 dispatch. The officer who discharged the firearm and other officers who witnessed the incident must immediately notify the 911 dispatcher, whether or not a death or wounding occurs.

- Call emergency medical services. The officer who discharged the firearm and other officers who witnessed the incident must immediately call EMS to evaluate the subjects of a firearm discharge.

- Medical release before transporting. If EMS transports the person to a hospital, the officer must obtain a medical release from the hospital before transporting the person to a detention facility. EMS personnel will be advised of the nature of the force used during the event.

1.5 Reporting and Investigation

A. Documenting and Reporting

- Reporting the Incident. When an officer discharges any firearm, whether on-duty or off-duty (with the exception of legal recreation or training purposes), and regardless of the type of firearm, the officer and any other officer who witnesses the incident must immediately report the incident to their supervisor. The discharging officer and witnessing officers must complete the appropriate use of force reports.

- Documenting the Incident. Officers must document in writing all incidents where they point a firearm at a person.

- Witnessing Officers. Officers must document all incidents where they witness or receive a report that another officer pointed a firearm at a person.

- Unholstering Firearms. Officers must document all incidents where they unholster a firearm, except for administrative or incidental unholstering like maintenance, target practice, or undressing.

B. Collecting Evidence

- Firearm as Evidence. Whenever an officer discharges a firearm in the line of duty, the firearm must be collected and submitted as evidence in accordance with department evidence collection, packaging, and submission policies.

- Body-worn Camera Footage. The body worn camera footage of each officer present at the scene at the time the officer discharged the firearm must be collected and submitted as evidence in accordance with department evidence collection, packaging, and submission policies.

C. Investigation

- Firearm discharge investigation team [or the Department’s nearest equivalent]. The firearm discharge investigation team must investigate any intentional or unintentional discharge of a firearm, other than for training purposes. The firearm discharge investigation team has sole responsibility for investigating firearm discharges involving a member of the Department.

- Independent Investigation. Where the discharge of a firearm results in death or serious bodily injury, the Department must relinquish control of the investigation to the District Attorney’s Office. Where an officer discharges a firearm resulting in injury, the District Attorney’s Office will be notified and designate a representative to conduct an independent investigation to determine the facts of the case.

- Police Chief's Determination. Upon receiving a report pertaining to a firearm discharge and investigation by the firearm discharge investigation team, the police chief may accept it or return the report with a request for further information or clarification. In every case, the authority and responsibility for final Departmental disposition of a firearm discharge incident rests solely with the police chief.

Endnotes

- For an example of an accidental discharge, see U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Civ. Rights Div., "Investigation of the Cleveland Division of Police," 18 (2014).

- See Ashley Fantz et al, "Texas Pool Party Chaos: ‘Out of Control’ Police Officer Resigns," CNN (June 9, 2015, 10:33 PM) (describing an incident where a police officer drew his weapon in response to a disturbance caused by teenagers at a public pool).

- See, e.g., Chad Flanders & Joseph Welling, Police Use of Deadly Force: State Statutes 30 Years After Garner, 35 Saint Louis University Public Law Review 109, 136-56 (2015) (collecting state statutes regarding the authorization of the use of deadly force, as of 2015); Debra Cassens Weiss, "Lethal Force Laws Reexamined After Police Killings; Is Reasonableness Standard Too Easy?," ABA JOUR-NAL (June 19, 2020) (“[S]tate laws generally permit police officers to use deadly force when they reasonably think their lives or the lives of others are in danger.”); Cynthia Lee, Reforming the Law on Police Use of Deadly Force: De-Escalation, Pre-Seizure Conduct, and Imperfect Self-Defense, U. ILL. L. REV. 629, 656-61 (2018) (surveying the existing differences between states on both necessity and proportionality with regards to use of force by police officers).

- The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, "New Era of Public Safety: A Guide to Fair, Safe, and Effective Community Policing," 116-117, 120 (citing Graham v. Connor, 490 U.S. 386, 388-90, 396 (1989) (2019).

- See Karen L. Amendola, Maria Valdovinos & Cesar Perea, Nat’l Police Found. & spcaLA, "An Evidence-Based Approach to Reducing Dog Shootings in Routine Police Encounters: Regulations, Policies, Practices, and Training Implications," 6-7 (2019) (highlighting the need for training for law-enforcement officials in interactions with dogs other than K-9s).

- See Ray v. Roane, 948 F.3d 222, 227 (2020).

- ASPCA, "Position Statements on Law Enforcement Response to Potentially Dangerous Dogs," (last visited Jan. 1, 2021).

- See President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing, "Final Report of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing," 21 (2015) (recommending “at a minimum, annual training that includes shoot/don’t shoot scenarios and the use of less lethal technologies”).

- See, e.g., Int’l Ass’n of Chiefs of Police, "National Consensus Policy & Discussion Paper on Use of Force," 4 (rev. 2020) (proposing in model policy that regular training be provided to teach “techniques for the use of and reinforce the importance of de-escalation,” and “enhance officers’ discretion and judgment” in decisions to use force); Police Exec. Research Forum, "Re-Engineering Training on Police Use of Force," 54-55 (2015) (statement of Deputy Chief Danielle Outlaw of Oakland, CA Police Dep’t) (describing the use of scenario-based training for firearms qualifications, where “the scenarios don’t always escalate to lethal force,” so that officers no longer “associate the firing range with merely shooting our weapons”); id. at 58 (statement of Captain Mike Teeter of Seattle Police Dep’t) (“Every applicable section of our tactics training includes aspects of deescalation training.”).

- See New Era of Public Safety, supra note 4, at 135.

- See New Era of Public Safety, supra note 4, at 135, 144.

- See New Era of Public Safety, supra note 4, at 135; President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing, supra note 8, at 21 (explaining that “[s]trong systems and policies” that encourage external reviews of police uses of force, especially uses of force that result in injury or death, can promote “transparency to the public” and “lead to mutual trust between community and law enforcement”).