First Amendment Activity and Crowd Management

Clear and comprehensive policies on First Amendment activity and crowd management can protect officers and community members while providing important transparency and accountability.

- Introduction

- Key things to know

- Understanding Policies on First Amendment Activity and Crowd Management

- The Policy

- Endnotes

Introduction

Why are policies on managing crowds and safeguarding First Amendment rights important for police and the communities they serve?

Crowd management situations are unique challenges, where public safety, constitutional rights, and community relations intersect in a high-profile environment. The dynamics of a crowd—sometimes unpredictable and charged—make the appropriate use of force by police a matter of critical importance. Managing these situations, with their fluid circumstances and wide spectrum of potential hazards, calls for clear and comprehensive policies that contemplate a range of potential scenarios.

Drawing from research and leading practices, this module probes the importance of finely calibrated strategies for managing crowds, while safeguarding the democratic right to assemble and protest. It underscores that using force to counter demonstrators should be considered a last resort and that the primary role of law enforcement is to facilitate constitutionally protected expressions of speech while safeguarding life. With proper training and policy implementation, law enforcement can play a constructive role in crowd management, promoting peaceful engagements and preventing unnecessary uses of force.

Downloads

Policy on First Amendment Activity and Crowd Management

Download the model policy on First Amendment Activity and Crowd Management.

Download PolicyFull Model Use of Force Policy

Download the Full Model Use of Force Policy – 10 detailed policies designed to help communities implement more effective use of force policies that enhance community safety while minimizing unnecessary force.

Open Full Model Use of Force PolicyKey things to know

- Police play an important role in safeguarding First Amendment rights and facilitating lawful assemblies, demonstrations, and protests while keeping the peace.

- When a police department becomes aware of a demonstration, it must plan in advance, when possible. This should include discussions with event organizers and information gathering.

- If people in the crowd engage in unlawful activity, officers must first use de-escalation.

- If enforcement is required, it must be directed at the specific people breaking the law and not the crowd more generally. Minor violations of the law should not be used as a basis to disperse an entire crowd.

- People have a right to record the public activity of police officers. Officers are not permitted to interfere with a person’s lawful recording and may not consider the act of recording, on its own, as unlawful or suspicious activity.

- Police may not use canines, water cannons, rubber or plastic bullets, or sound cannons to control or disperse a crowd. Tear gas may only be used when authorized by the commanding officer and in response to crowd violence.

Understanding Policies on First Amendment Activity and Crowd Management

Political demonstrations, protests, and other mass gatherings are important, fundamental aspects of American life, dating back to the nation’s founding. Indeed, for many, the right to peacefully protest is a crucial component of what it means to be an American and live in a robust democracy.[1]

Just as police officers have responsibility over enforcing traffic laws to ensure that roadways remain safe for drivers, officers also have responsibility over enforcing laws that ensure that citizens can exercise their rights to lawfully demonstrate and protest in public. The First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution guarantees the public’s rights of freedom of speech and assembly.[2] Police officers commonly swear an oath to uphold and defend the Constitution, and the Constitution sets limits on how governments may interact with their constituents.[3] These limits apply to law enforcement officers at all levels: federal, state, and local.[4]

While the First Amendment offers broad and important protections for the freedoms of speech and assembly, it does not provide absolute protection. Officers should be well trained in the regulations that may be applied to speech—protected and unprotected. In general, the First Amendment does not give demonstrators the right to venture onto private property, even to engage in expressive political speech, if the property owner does not consent to their presence.[5] Protestors who use public areas can be required to comply with restrictions on the time, place, and manner of their activity, so long as those restrictions apply to all expressive activity without distinguishing on the basis of content.[6] And the First Amendment does not protect certain categories of speech: for example incitement—which refers to speech that has the effect of likely inciting imminent unlawful action and has the intent to have such effect—does not receive First Amendment protection.[7]

Policing challenges posed by assemblies, demonstrations, and protests

Large demonstrations can present significant challenges for officers assigned to observe these assemblies, as protected speech may occur at the same event and in the same vicinity as unprotected speech or unlawful behavior that threatens the continuation of the protest. Demonstrations that occur in public spaces generally do not involve closed systems, and lawful demonstrators with legitimate aims may have a demonstration coopted by people with different purposes. Officers who are present at these protests to facilitate non-violent, lawful, and constitutionally protected activity must monitor the crowd for: changes to the group makeup, the nature of the activity occurring within the demonstration, and even shifts in the “mood” or “tone” of the demonstration. Observing the crowd helps to identify when a lawful assembly may give way to violent or otherwise unlawful activity.[8]

Officers do not have a simple task during protests: the Constitution prohibits them from interfering with lawful First Amendment activity, which is likely to be the majority of the activity at most demonstrations and gatherings. At the same time, officers also have a mandate to preserve the peace, which requires them to be prepared to recognize and react to unlawful activity that may arise within the context of a peaceful demonstration or in opposition to it. To react appropriately to the changing makeup of a crowd, officers must be comfortable recognizing when such changes have occurred and determining how to respond to violence or illegal activity so that a lawful demonstration can continue—and such decisions must often be made quickly.

While the Model Policy sets forth requirements and strategies to help departments plan for and address challenges presented by demonstrations, a department’s effective response to demonstrations also depends on the department’s preparations outside of the scope of this policy. As with all police work, officer training and a department’s long-term preparations are crucial to the ability to act effectively, strategically, and constitutionally in moments when quick reactions are necessary.

In particular, the Model Policy begins with a pronouncement that it seeks to protect individual rights to free speech and assembly. The Policy recognizes that demonstrations and assemblies are valued activity within the culture of the United States. To effectuate this policy statement, departments must take longer-term actions outside the scope of the policy itself, to ensure that officers are familiar with the contours of the First Amendment rights that they are sworn to protect, and that the department promotes a culture that respects those rights for demonstrators regardless of the views that the demonstrators express.

In addition, efforts by the police department and officers to build relationships with the communities they serve allow them to be more effective in preparing for—and monitoring—mass demonstrations. The Model Policy directs a department’s officers to gather information once they become aware that a demonstration is planned or expected, including identifying the event organizers, estimating the number of attendees, and understanding the history of similar events in the community. While the department may be able to obtain some of this information from sources other than the event organizers or participants, the policy recommends that the department make contact with event organizers directly to facilitate planning and preparation. Interactions between a department and the community members planning a demonstration will be easier if the department has a pre-existing relationship with the event organizers or with related community groups.[9]

Preexisting relationships between a police department and community groups will be particularly important when, as was the case in cities across the U.S. in the summer of 2020, policing practices themselves become the subject of demonstrations.[10] One report on police responses to protests refers to “[r]egular communication between police and communities [as] akin to making regular deposits into a savings account,” which can “establish a positive balance of trust and goodwill” that may help “cover the inevitable moments when a controversial arrest or use-of-force incident results in a withdrawal from the account.”[11]

Many elements that can contribute to effectively policing demonstrations therefore require long-term commitments beyond the scope of this policy: instituting a culture of respect for First Amendment rights, building community relations, and equipping officers at every level with the knowledge and training to respond reasonably to changing circumstances in a manner that balances demonstrators’ rights with officers’ duty to enforce the law. Some foundation in each of these areas may be required to effectively implement the Model Policy’s provisions, as officers without some knowledge of the First Amendment and appreciation for its protections will struggle to differentiate between lawful speech and unlawful activity. However, if a department has established a baseline of knowledge and training for its officers and has fostered a culture that respects the rights of demonstrators, the Model Policy builds on that baseline to establish guidelines for the department’s strategic and tactical approaches to policing demonstrations and other crowd events.

Principles based on research into leading crowd management practices and tactics

The Model Policy’s approach to First Amendment activity and crowd management relies, in part, on a report by criminal justice researchers Edward R. Maguire and Megan Oakley, “Policing Protests: Lessons from the Occupy Movement, Ferguson & Beyond: A Guide for Police.”[12] The report, published in January 2020, reviews the history of protest policing in the United States, then draws from social science literature, reporting on police responses to recent demonstrations, and interviews with officers, to develop strategic recommendations for law enforcement agencies in planning and executing these responses. Although the researchers completed this report before the summer of 2020, and therefore the report does not account directly for the police responses to mass demonstrations across the U.S. in May and June of 2020, the report’s observations, which draw from police experiences with the early 2010s Occupy movement—and the strategic recommendations the report reaches from those observations [13]—offer continuing lessons for police departments responding to demonstration activity.

Indeed, following protests in New York City in 2020, which included several high-profile instances of perceived police overreach or excessive force,[14] the New York City Department of Investigation undertook an investigation into the New York Police Department’s (NYPD) response to the protests. The Department of Investigation issued a report in late 2020[15] that drew on Maguire and Oakley’s research in making its own recommendations for the NYPD.[16]

Maguire and Oakley’s recommendations—which they note are “principles and strategies,” rather than detailed “tactics” of policing—articulate four concepts that should inform a law enforcement organization’s approach to policing demonstrations: education, facilitation, communication, and differentiation.[17]

- “Education” involves learning about community groups, their leadership, and other groups likely to be present at demonstrations, so that officers are better prepared to observe group dynamics and plan responses.[18] Education also involves building relationships with other law enforcement agencies for the purpose of sharing experiences and best practices, as agencies may encounter similar challenges in policing certain types of demonstrations.[19]

- “Facilitation” requires that police responses to demonstrations be oriented toward creating and maintaining a safe environment for lawful activity, including lawful activity protected by the First Amendment rights to free speech, assembly, and freedom of the press. Maguire and Oakley note that “[w]hen police operate from the vantage point of how to facilitate peaceful protests rather than how to control, regulate or manage” protesters—for example, to preemptively head off any potential “destructive or violent” behavior—they can avoid creating an impression of “over-controlling or micromanaging” protected activity, and actually improve community relationships while “minimiz[ing] the likelihood of conflict and violence.”[20]

- “Communication” emphasizes the importance of providing reliable information to protesters and to the media, as well as engaging in dialogue with protesters before and during an event.[21]

- “Differentiation” draws from crowd psychology studies, to emphasize that a police response that treats a crowd as “homogeneous” is usually inappropriate because crowds typically contain “moderate” members along with any “more radical or extreme members.”[22] A police response that reacts to individual instances of lawbreaking by “taking unilateral action against the whole crowd” can have the effect of causing moderate crowd members to align with the more radical members against the police, escalating tensions between police and protestors.[23] Differentiation “must be ‘built into every tactical or strategic decision’” a department makes in policing a demonstration, from deciding how many officers to send to a demonstration and what equipment they will carry, to determining when and how to execute arrests in the event that members of a crowd engage in unlawful activity.[24]

These four principles are substantially intertwined, and each builds on the others. For example, a facilitative department culture will promote building relationships with politically active community groups, where another department might otherwise be inclined to view these groups as nuisances at best. Education in advance of a demonstration will facilitate communication with the participants while the demonstration is occurring. An effective differentiated response requires education on the groups present and the nature of the event planned, as well as a facilitative department culture that recognizes the value of lawful political activity, and ongoing open lines of communication with participants in the demonstration.

The Model Policy’s approach to safeguarding First Amendment activity and managing crowds

The principles of facilitation, education, and differentiation dictate the structure of the Model Policy’s approach to safeguarding First Amendment activity and managing crowds. The first provisions in the policy are statements of values, which reinforce in writing that the department values the First Amendment and the exercise of First Amendment rights, and that the department’s response to a demonstration will have the primary goal of facilitating lawful demonstration activity. The introductory statements note that this goal of facilitating lawful demonstration activity requires officers to continue enforcing laws, that demonstrators have rights to free speech and assembly, and that the department values these rights as much as it values the lives and safety of all members of the public.

Following the introductory policy statements, the policy discusses procedures that a department should undertake when it receives word of a planned or spontaneous demonstration. First among these preparatory steps is “education” in the form of information gathering, which will form the basis for the written plan that governs the department’s response. Questions that the Model Policy asks the department to investigate are adopted from an International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) model policy and a policy from the San Diego Police Department.[25] These questions will aid officers in identifying logistical concerns, which may be as simple as traffic flow, and determining the resources needed to adequately address those concerns.

The information-gathering questions also direct officers to find out which groups will be present at a demonstration, how those groups relate to one another, and what the various participants’ goals will be. The policy recommends that, whenever time and circumstances allow, officers should obtain this information from the demonstration’s planners and participants themselves. This emphasis not only ensures that officers receive information from the sources most likely to have reliable information on the demonstration, but it also encourages officers to build a relationship with the event organizers, a practice that some departments find central to a successful demonstration response.[26] This information gathering—and, ideally, communication—will help the department to execute a differentiated response, as awareness of the groups on the ground and their motivations should prepare officers to recognize these various groups at the event.

The Model Policy is organized so that, unless the department receives information to the contrary, the department presumes a planned demonstration will be a lawful, peaceful event, and that by default, the initial police response will be by officers in ordinary patrol uniforms. The policy discusses demonstrations in these terms first, before introducing the separate concept of a “civil disturbance,” which is a designation that only the incident commander for the demonstration can make and which is a necessary precondition to any dispersal order, coordinated force response, or mass arrest.

The policy also incorporates differentiation as an explicit component of its provisions. In application, differentiation can resemble a demonstration-specific form of de-escalation, a principle of policing that is addressed, incorporated, and repeated throughout other chapters of the policy. This module discusses differentiation and de-escalation together. When combined on the individual level these principles require officers to (1) calibrate force responses, where necessary, to individuals rather than to groups, and (2) use the lowest level of force possible, with escalation only in response to escalation by the individual.

On the supervisory or planning level, the principles of differentiation and de-escalation ask departments to plan demonstration responses with the assumption that demonstrators are law-abiding and peaceful, unless specific information indicates that a different response is needed. Even where an escalated response may become necessary, de-escalation and differentiation require that additional officers or protective equipment should be staged out of sight of the demonstration activity, as a heightened police presence is itself a show of force that demonstrators may perceive as an escalation.

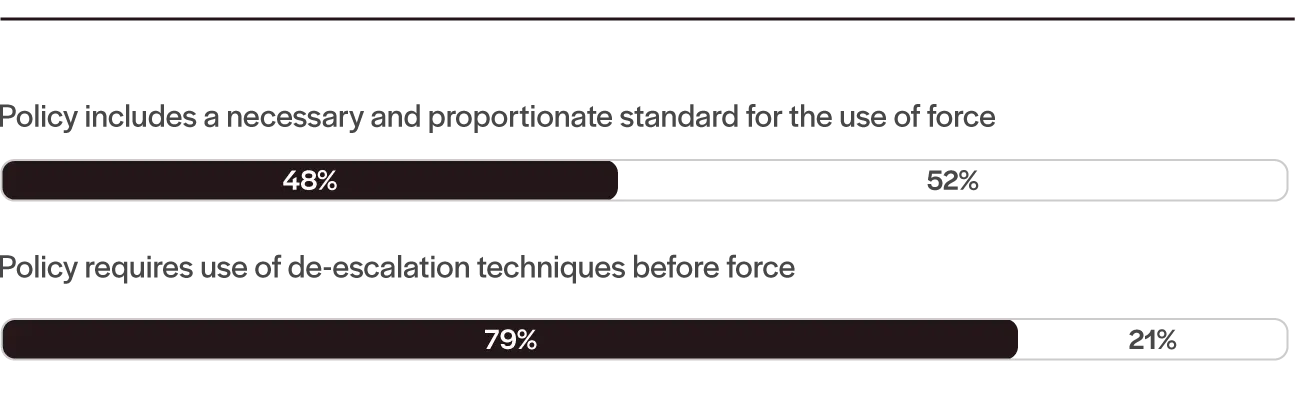

Key Force Regulations in Policies of 100 Largest U.S. Cities

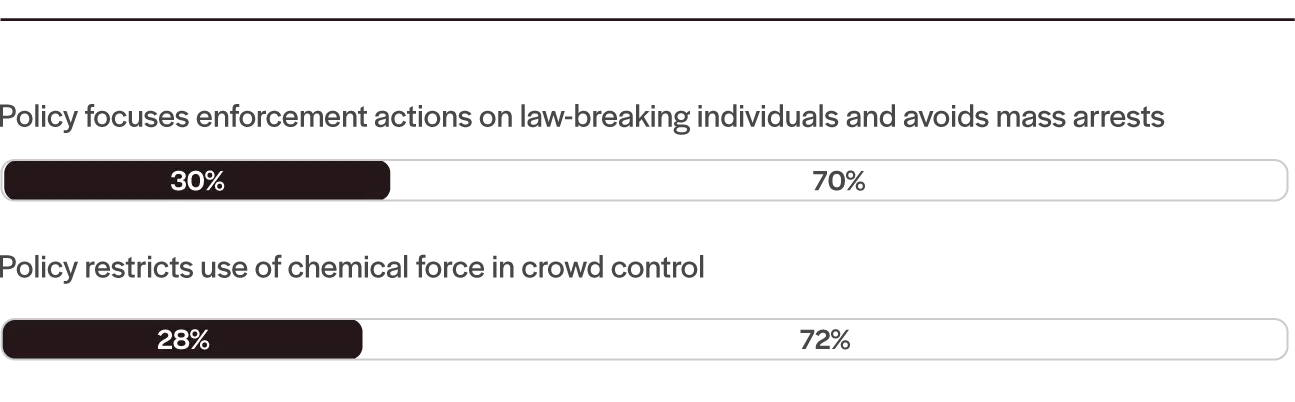

Crowd Management Regulations in Policies of 100 Largest U.S. Cities

Crowd control tactics and civil disturbances

Large demonstrations involve great numbers of individual people and groups, all of whom may have different motivations and demonstrate different behaviors.[27] Demonstrations generally do not involve closed systems, and even the best planned peaceful demonstration may attract counter-protestors or other unaffiliated groups whose presence can alter the dynamics of the event. Because demonstrations can involve rapidly changing circumstances, officers should be trained to observe these shifts and communicate these developments as they arise so that an updated police response can be coordinated.

But the Model Policy follows the lead of some recently updated policies in centralizing many decisions surrounding an escalated police response in department leadership: supervisors, a designated incident commander, and in some instances, a department’s chief. While individual officers should still be trained to exercise their best judgment in the event of an unavoidable contingency that requires an escalated response—for example, an arrest or use of force against an individual demonstrator engaged in violence—the Model Policy adopts the position that an effective demonstration response requires strategic thinking and coordination at a high level. As a result, major decisions involving arrests, dispersal, and uses of force are reserved in all but exigent circumstances to an incident commander or equivalently positioned officer who can make strategic decisions regarding the whole police response.

This centralization of authority in an incident commander is crucial to the Model Policy for two reasons. First, coordination reduces the risk that officers will issue contradictory orders, a phenomenon that can disorient and frustrate demonstrators and have the effect of reducing officers’ legitimacy. A department that coordinates and issues clear, well-planned orders and enforces them uniformly is more likely to benefit from demonstrators’ continued respect and goodwill.[28]

Second, and more significantly, centralizing key decisions in one incident commander limits the discretion of individual officers. This limitation may be a significant change from the way that some departments currently implement their protest responses. Discretion has been understood by some to be a central component of the individual police officer’s role in the modern era,[29] and the optimal degree of officer discretion is a key consideration throughout other sections of the Model Policy as well. In the context of demonstrations, though, leaving individual officers with the discretion to engage in potentially escalatory actions can create tense relations between officers and demonstrators that might otherwise be avoided. Officers are required to act neutrally regardless of the subject of a demonstration and the views espoused by demonstrators, but that requirement can pose a challenge when, for example, police practices are the subject of the demonstration.[30]

In high-tension environments, officers closest to the demonstration may perceive demonstrators to be antagonists,[31] and if those officers have broad discretion to execute arrests or use force against demonstrators, they may perceive such escalations to be necessary—even where a supervisor with a more removed, strategic view would not perceive the escalations to be necessary or helpful to the goal of facilitating a lawful demonstration. By limiting the discretion of individual officers to declare a demonstration unlawful, issue an order to disperse, and execute arrests or use force under certain circumstances, the Model Policy encourages strategic consideration before police undertake any escalations in response to demonstrators’ activity.

Civil disturbance declaration: a significant step that requires careful consideration

The Model Policy provides that only the incident commander may declare a civil disturbance and provides a list of factors that the incident commander must consider in that decision. These factors, adopted from the San Diego Police Department’s policy, revised in 2021, require the incident commander to consider the prevalence, proportion, and type of unlawful activity occurring, and whether any more facilitative or more targeted responses could adequately address the identified unlawful acts.[32]

State law may give a different definition for a civil disturbance, an “unlawful assembly,” or similar term.[33] The department’s policy must incorporate any underlying state law, but need not—and should not—merely recite the state law requirement for this designation. Instead, the policy contemplates that the factors the incident commander must consider should be overlaid on top of any state law definition, so that the incident commander answers two questions before designating a civil disturbance: (1) are the requirements for designating a civil disturbance under state law met, and (2) under the specific conditions of this assembly, is it necessary to declare a civil disturbance, or are there additional, intermediate measures that may be sufficient to control the unlawful activity? As the declaration of a civil disturbance or unlawful assembly will be followed by an order to disperse or other enforcement,[34] such a declaration should not be made before all other reasonable options have been exhausted.[35]

When should police issue a dispersal order?

Upon the incident commander’s declaration of a civil disturbance, this designation must be communicated clearly to the officers who will be charged with the enforcement associated with that designation. Except in circumstances where the unlawful activity that justified the declaration is so widespread and severe that mass arrests are immediately warranted, the first enforcement action taken should be an announcement that a civil disturbance has been declared and the issuance of an order to disperse.

The goals of a dispersal order must be to communicate clearly that the demonstration has been deemed unlawful and cannot lawfully continue and to obtain voluntary compliance by demonstration participants with the order. Accomplishing these goals requires coordination to ensure that: (1) the dispersal order can be heard and understood by the persons present and (2) demonstrators have an egress route or other routes available so that they can disperse safely. The order must communicate basic information: the date and time, the number of times the dispersal order has been announced, the identity of the announcing officer, the reason the demonstration has been deemed a civil disturbance, a clear statement that all demonstrators are required to disperse, the permitted direction of egress, and a statement that refusing to disperse may result in arrest.

This message must be announced in a manner sufficient to ensure that the dispersal order is audible to all demonstrators. A sound delivery system should be used when available, so that the whole assembled group can hear the same message delivered by one officer. If this technology is not available and multiple officers are announcing the dispersal order, the message should be written and read out, to ensure that each officer delivers the same announcement. The dispersal order should be repeated at least twice after the initial reading, with a reasonable amount of time between each reading to permit individuals to comply with the order and leave the area. Each reading of the dispersal order should be audio- or video-recorded.[36]

What force options do officers have in crowd situations?

Like the decisions to designate a civil disturbance and issue a dispersal order, decisions regarding the use of force against individuals present at a demonstration have strategic implications. These decisions should be centralized in the incident commander, except where exigent circumstances require an individual officer to react.

Many details about the authorization of the use of force and various force options will be covered in other modules of the Model Policy or a department’s other policies. For example, separate policies regarding the use of batons, pepper spray and other forms of oleoresin capsicum, and deadly force apply fully in the context of a demonstration and civil disturbance. For those force options, this module discusses strategic considerations only. The module emphasizes that these force options should be used in accordance with the crowd management principles of facilitation and differentiation, and that these force options should be in line with directives from the incident commander.

Certain force options appear only—or primarily—in the context of demonstrations and mass assemblies, and the Model Policy provides new guidelines for these force options. The Model Policy acknowledges that police lines can be a show of force, and the deployment of officers in formal line formations should be carefully considered as these shows of force may be perceived as escalations by members of the public. Police lines also can operate in formations that constitute uses of force, such as when officers use shields, batons, bicycles, barricades, or direct bodily contact to forcibly move individuals who are unlawfully present in an area.[37] These coordinated shows and uses of force are subject to the direction of the incident commander and supervisors, and must otherwise be undertaken in compliance with the department’s policy on physical force and impact weapons.

On the other hand, the Model Policy categorically prohibits the use of certain force options previously associated with police responses to demonstrations. For example, this module bans the use of canines and water cannons for crowd control—practices that were common in police responses to the civil rights protests of the 1960s but have since been banned in many jurisdictions’ existing policies.[38]

The policy also imposes significant limitations on the use of other crowd-control force options that remain in use: kinetic impact projectiles (or “extended range impact weapons”), pepper spray or balls, and chemical force such as tear gas. These categories of weapons have historically been classified as “less-lethal” or “non-lethal” force options, as compared to lethal force, like the use of firearms.[39] Each of these weapons, though, is susceptible to misuse that may result in force disproportionate to the danger posed by demonstrators. High-profile incidents in recent years have shown the acute dangers of misusing each of these categories of force. In the Summer 2020 demonstrations for racial justice and against police misconduct, demonstrators in several cities suffered fractured facial bones, vision loss, eye loss, traumatic brain injuries, and damage to reproductive organs from police-fired “less-lethal” projectiles.[40]

Pepper spray can also cause blindness[41] and can be especially dangerous when used on individuals who are young, elderly, or in frail health.[42] In the context of demonstrations and civil disturbances, the imprecise or indiscriminate use of pepper spray and tear gas can result in serious injuries. For example, after the Supreme Court ruled to overturn federal abortion rights, in multiple places, police met protestors with chemical force in the form of tear gas, causing injuries to peaceful protestors.[43] Scientific research has not confirmed a causal link between tear gas and miscarriages, but exposure to tear gas has been anecdotally linked to changes in individuals’ menstrual cycles,[44] suggesting that the effects of this exposure are not sufficiently understood.[45] Further, the known effects of tear gas include respiratory responses like lung inflammation, which may be exacerbated by underlying conditions like asthma and COVID-19,[46] conditions that officers may not adequately account for when using tear gas in a crowd setting.

During and after the Summer 2020 demonstrations, courts and legislatures responded to allegations that law enforcement indiscriminately used less-lethal munitions against demonstrators by restricting police use of these weapons—in some instances temporarily,[47] and in others permanently.[48] For instance, in Black Lives Matter Seattle-King County v. City of Seattle, Seattle Police Department, a U.S. District Court granted a temporary restraining order enjoining Seattle police from deploying chemical weapons or projectiles for purpose of crowd control at civil rights protests or demonstrations, including prohibitions on any chemical irritant such as tear gas or pepper spray and any projectile such as flash-bang grenades, ‘pepper balls,’ ‘blast balls,’ and rubber bullets.[49]

These injunctions and policy changes reflect that it can be difficult in a crowd setting to use these weapons in a manner that distinguishes lawful demonstrators from individuals engaged in unlawful activity, and that the effects of these weapons are not fully known, meaning that the magnitude of damage they inflict can be difficult to predict. The Model Policy recognizes that some uses of these weapons may be justified by imminent threats of unlawful activity by a crowd engaged in widespread violence, and does not foreclose the possibility that tear gas, pepper spray, or kinetic projectiles may be justified in limited circumstances. However, the policy recognizes that each of these “less-lethal” or “non-lethal” force options can cause lasting damage to exposed individuals, and limits the situations in which the incident commander or police chief may authorize the use of these weapons.

Long range acoustic devices (LRADs) are sound cannons that can be used to communicate over long distances, but which can also be used to emit a sound of 140-150 decibels—a volume that may cause permanent hearing damage after a second or more of exposure.[50] To settle a lawsuit following the use of an LRAD’s “deterrent” tone at a 2014 protest, the NYPD agreed not to use the LRAD “deterrent” tone and to issue additional guidance on using LRADs for communication purposes—in addition to paying damages and legal fees to demonstrators who alleged hearing damage, migraines, tinnitus, and other symptoms following exposure to the “deterrent” tone.[51] The Model Policy follows the NYPD’s decision to prohibit the use of the LRAD’s deterrent tone in all circumstances.

Mass arrests must be a last resort

The Model Policy recognizes that in certain circumstances where unlawful activity is severe and widespread, it may be necessary to engage in simultaneous arrests of a group of people. However, mass arrests are strongly disfavored. In general, the arrest of a group will raise constitutional concerns, including about whether probable cause can be articulated to justify the arrest of each individual in the group. Further, the arrest of a group can present significant logistical challenges for the department, which will need to ensure that anyone detained is treated humanely and has access to food, water, bathrooms, and necessary medical treatment.[52] The Model Policy adopts guidance from the Albuquerque and Cleveland police departments’ highly detailed policies regarding mass arrest procedures, to guide departments in preparing for and executing mass arrests safely and in an orderly fashion that respects the constitutional rights of the individuals arrested.[53] The logistics of mass arrests are complex and departments should modify this policy as necessary to meet the needs and characteristics of their jurisdictions, but any modifications should still be calculated to advance the purposes of (1) limiting the situations in which mass arrests are authorized, by encouraging de-escalation and differentiation; (2) documenting arrests, including the identity of the arresting officer and the charges justifying arrest; and (3) meeting arrestees’ basic needs for as long as they are in custody.

Special First Amendment considerations: investigative use of social media and recording of police activity

Along with its primary subject matter of First Amendment-protected demonstration activity, this module addresses two related policy areas where First Amendment protections are implicated: police use of social media for investigations, and the recording—audio, photographic, or video—of police activity in public areas.

Investigative use of social media

The Model Policy recommends that a department conduct its information gathering by contacting event organizers, to the extent practicable. As discussed above, one goal of this provision is to encourage officers to form relationships with politically active community groups. A secondary goal of this provision is to promote the use of tools other than social media for information-gathering.

While departments may have preexisting rules regarding the use of social media for investigative purposes—and this module assumes that a department sets forth its general approach to social media elsewhere in its policies—the use of social media to investigate an anticipated, lawful First Amendment-protected demonstration can raise First Amendment concerns of its own. For example, if law enforcement search and view specific activists’ pages, this may result in unconstitutional surveillance of these individuals or groups on the basis of their political beliefs. The policy recognizes that while good police work, including but not limited to information gathering to prepare for demonstrations, may require the use of social media, this use should be carefully constrained to ensure that officers do not overreach and conduct surveillance of constitutionally protected activity.[54]

Because social media will likely be an investigative tool that officers use outside the context of demonstrations, the details of a well-calibrated, comprehensive social media policy are beyond the scope of the Model Policy. This module ultimately assumes, therefore, that the department has a separate social media policy that prohibits unconstitutional surveillance and requires that any social-media use related to demonstrations comply with that general policy.[55]

The constitutional right to record police activity

The act of recording police activity that occurs in a public place, or is otherwise visible from a public location, is protected by the First Amendment.[56] This right is not limited to the contexts of political demonstrations, and the Model Policy notes that, as a best practice, officers should act as though their activities may be recorded any time they are engaged in official police work in a public area.[57]

The policy requires officers to take a facilitative and differentiated approach to persons recording police activity, which recognizes that such person is (1) engaged in lawful activity and (2) not inherently subject to increased suspicion by virtue of recording police activity. Like demonstration activity, recording the police is a lawful, constitutionally protected activity that can have benefits for a community, and officers should be aware that interfering with or targeting a person who has recorded police activity will not be tolerated. The Model Policy draws from the IACP model policy, as well as from the policy on recording police activity that the Minneapolis Police Department adopted in 2016, which is protective of the public’s right to observe and record police activity and clear that officers cannot interfere with recording activity if the individual is a safe distance away and lawfully present.

This Minneapolis policy already was in effect in May 2020, when a number of bystanders took video recordings of the encounter between Minneapolis police officers and George Floyd.[58] Floyd’s death during that encounter was originally reported as a “medical incident.” The bystanders’ video recordings showed instead that an officer had knelt on Floyd’s back and neck for several minutes, while officers ignored Floyd’s insistence that he was unable to breathe in that position. The circulation of these recordings brought the circumstances of Floyd’s death to public attention, leading to worldwide demonstrations for racial justice and against police misconduct, and ultimately contributing to a jury verdict that the officer who knelt on Floyd’s neck, killing him, was guilty of murder.[59] The video recording of George Floyd’s murder was not the first time that a bystander recording has brought police misconduct or brutality to light, but it underscores how crucial these recordings can be to achieving some measure of accountability.[60]

While officers may perceive recording activity as annoying or hostile, the recording of police activity can have the effect of increasing public trust in police. Officers may be recorded carrying out their duties professionally and according to department policies. And if the public sees that officers who are recorded violating department policies are disciplined, it can promote trust by demonstrating that the department takes violations seriously. The Model Policy thus requires officers to tolerate recording and prohibits them from interfering, except where the person recording is physically obstructing police activity and refuses to move voluntarily.

The Policy

1.1 – Key Concepts and Definitions

A. Key Concepts:

- The Department’s officers play an important role in safeguarding First Amendment rights and facilitating lawful assemblies, demonstrations, and protests while keeping the peace.

- Officers must differentiate between lawful speech and assembly activity, on the one hand, and unlawful or violent acts of individuals or groups within a crowd.

- If individuals or groups within a crowd engage in unlawful or violent acts requiring intervention, officers should respond in a manner that minimizes the use of force and has a minimal impact on any remaining, ongoing lawful activity.

B. Definitions:

-

Demonstration: An assembly of persons organized for the purpose of engaging in constitutionally protected speech. Demonstrations may include marches, protests, speeches, press conferences, and other assemblies. Demonstrations are not Civil Disturbances, but a subset of attendees at a Demonstration may cause a Civil Disturbance requiring enforcement action.

-

Civil Disturbance: An unlawful assembly that constitutes an immediate threat to public safety or public order in the form of imminent threats of widespread violence, destruction of property, or other unlawful acts.

-

Crowd Management: Techniques used to manage lawful assemblies before, during, and after the event for purposes of maintaining the event’s lawful status and facilitating the exercise of constitutional rights. Crowd management techniques include, but are not limited to, pre-event contact with organizers of the event, information gathering, training, and communication throughout the event.

-

Crowd Control: Techniques used to address mass assemblages of people, Demonstrations, and Civil Disturbances, including shows of force, crowd containment, dispersal equipment and arrests, and preparations for mass arrests.

-

Incident Commander: The Department's designated supervisor with responsibility for the Department's response to a Demonstration.

-

Necessary: Force is necessary only if there are no other available non-force options or less-forceful options to achieve a lawful objective.

-

Resistance: Officers may face the following types of resistance to their lawful commands:

Passive Resistance: A person does not attack or attempt to attack the officer or another person, and does not attempt to flee, but fails to comply with the officer’s commands. Examples include, but may not be limited to, going limp, standing stationary and not moving following a lawful command, and/or verbally signaling their intent to avoid or prevent being taken into custody.

Active Resistance: A person moves to avoid detention or arrest but does not attack or attempt to attack the officer or another person. Examples include, but may not be limited to, attempts to leave the scene, fleeing, hiding from detection, physical resistance to being handcuffed, or pulling away from the officer’s grasp. Verbal statements, bracing, or tensing alone do not constitute Active Resistance. A person’s reaction to pain caused by an officer or purely defensive reactions to force does not constitute Active Resistance.

1.2 – Preparation and Response Strategy

A. Communication, Outreach, and Information Gathering

-

Outreach to Event Organizers. The Department will sometimes, but not always, have notice and the opportunity to prepare and plan for a Demonstration. When the Department receives notice of a planned Demonstration, officers should engage in outreach to the event organizers and/or demonstrators, discuss the planned event, and gather information that will assist the Department in facilitating lawful First Amendment activity and maintaining or establishing the peace.

-

Unplanned Demonstrations. When the Department becomes aware of an unplanned or spontaneous Demonstration, or if it is otherwise not possible to identify or contact Demonstration leaders in advance of a Demonstration, officers should similarly endeavor to gather this information.

-

Social Media Information. Event organizers and demonstrators often use social media to plan and share information about a Demonstration. When officers use social media to learn more about a Demonstration, plan a response, and follow the Demonstration, they must comply with the U.S. Constitution, state constitution, and all relevant policies of the Department on the use of social media for information gathering. Officers must ensure that this use of social media does not infringe upon individuals’ constitutional rights.

-

The types of information a Department should gather or learn more about a Demonstration include:

- What type of event is planned? How many participants are expected? When is it planned, and will the event coincide with other planned, large-scale events?

- What is the history of conduct at such events? Is opposition to the event expected? Who are the potential counter-protest groups? Is there a history of violence between the group demonstrating and potential counter-protest groups?

- What are the assembly areas and movement routes? What actions, activities, or tactics are anticipated? What critical infrastructure is in the proximity of the event?

- Have permits been sought and issued? Have other agencies, including the Fire Department or Emergency Medical Services (“EMS”), been notified?

- Has the appropriate level of personnel been allocated to ensure the safety of demonstrators, bystanders, and officers? Will off-duty personnel be required? Is there a need to request mutual aid?

B. Designating an Incident Commander

Upon learning of a Demonstration, whether planned or spontaneous, the Department must designate an Incident Commander with responsibility over the Department’s response to the Demonstration.

C. Planning

The Incident Commander has primary responsibility for developing and executing a written incident response plan.

-

Response Plan. The plan must consider the information gathered from community members and other sources and whether the Department expects the Demonstration to be non-violent.

-

De-Escalation. The Department’s planned response must be informed by the principles of de-escalation defined and discussed in the Department’s use of force policy. De-escalation principles suggest that the visible police presence should be limited, as practicable, to facilitate a Demonstration that the Department expects to be non-violent. These Demonstrations should generally require a lower level of resources from the Department.

-

Non-violent Demonstrations. Where the Department expects a Demonstration to be non-violent, the following general guidelines will apply:

- The minimum possible number of officers should be sent to monitor the Demonstration.

- Officers present at the demonstration should be in normal patrol uniforms with their badge numbers and identifying information visible.

- Officers should observe from a distance close enough to see Demonstration activity, but should consider the potential effects of police presence on the Demonstration and maintain sufficient distance to avoid agitating participants.

D. Differentiation in Response Planning

The Department’s planned response must at all levels be informed by the principles of differentiation.

- Differentiation recognizes that crowds are comprised of individual actors and distinct groups who have different behaviors and motivations, which requires officers to respond accordingly.

- Differentiation requires that the initial police response be tied to the minimum number of officers required to keep the peace, based on the Department’s advance planning.

- If the Department expects a Demonstration to be non-violent but has reason to believe that unlawful activity subsequently may arise during the Demonstration, differentiation requires a graded response: the police presence should be minimal, as long as the demonstration remains peaceful, but additional officers and resources should be available at a nearby staging area in the event more resources are required.

- For officers observing a demonstration in progress, differentiation requires that officers should observe the dynamics of the crowd and understand that a variety of groups may be present, including legal observers, members of the press, bystanders, and various groups of Demonstration participants, including counter-protesters. Should unlawful or violent behavior occur, differentiation requires that officers’ response should be targeted toward the individuals or groups acting unlawfully, rather than attributing disorderly behavior to the Demonstration as a whole.

- Planning for Contingencies. The Department’s written response plan must, to the greatest extent possible, anticipate various scenarios and devise a police response for these contingencies. If planned contingency responses require that armored vehicles, personal protective equipment, additional munitions, or additional officers be in the proximity of the Demonstration, the visibility of these officers or equipment must be minimized to the greatest extent possible.

1.3 – Crowd Control Tactics and Civil Disturbances

A. Responses to Unlawful or Violent Activity by Individuals or Groups

- If an individual or small group within an otherwise lawful Demonstration is engaged in unlawful activity, officers must direct any enforcement at the individual or individuals involved in breaking the law and may not attribute the unlawful activity to the Demonstration as a whole. Minor violations of the law should not be used as a basis to disperse an entire assembly.

- If a Demonstration or assembly becomes disruptive due to more widespread violent or unlawful behavior, supervisors must use their best efforts to develop and direct a gradual approach to restore order, consistent with the goal of preserving the health and safety of the participants and the public.

- If the Incident Commander determines that the circumstances at a Demonstration or other crowd event meet the definition of a Civil Disturbance, the supervisor must consider whether the violent or unlawful activity may be effectively mitigated or addressed without the further step of a declaration of a Civil Disturbance.

B. Evaluating and Declaring a Civil Disturbance

-

Factors to Consider. The Incident Commander will determine whether unlawful or violent acts at an assembly constitute a Civil Disturbance within the definition provided in this policy. If the circumstances meet the definition of a Civil Disturbance, the Incident Commander must consider whether the violent or unlawful activity may be effectively mitigated without the further step of a declaration of a Civil Disturbance. The Incident Commander must consider these factors:

- The nature and scope of the unlawful or violent activity, including: the threat presented to people or property, the prevalence and nature of violent and unlawful acts within the crowd, and whether the violent or unlawful acts are concentrated within small groups or occurring throughout the assembled crowd;

- The degree of internal conflict within the assembly (for instance, if previously separated groups have merged into one crowd);

- The effectiveness, or expected effectiveness, of contacting event organizers to facilitate de-escalation; and

- Whether the Department has sufficient police resources on-site to manage the incident effectively.

-

Additional Factors. The Incident Commander also may consider the following factors, but neither factor may be the sole basis for a decision to declare a Civil Disturbance:

- The fact that the assembly organizers lack a permit, such as a park, parade, or sound permit; and

- The fact that some Demonstration participants or involved groups have previously engaged in violent or unlawful acts.

-

Documenting the Decision. If the Incident Commander determines that circumstances warrant a declaration of a Civil Disturbance, the Incident Commander must document the violations of law and other factors that contributed to the decision to declare a civil disturbance.

-

Ensuring Necessary Resources Available. The Incident Commander must coordinate through designated communications channels to ensure the availability of sufficient officers and the required equipment to respond to the Civil Disturbance, as well as the required fire and EMS personnel and equipment.

-

Communicating Civil Disturbance Declaration. The Incident Commander must communicate the declaration of a Civil Disturbance to the assembly, in a manner that is audible and intelligible to all persons in the assembly. The announcement must state the date and time and explain the laws being broken or the reason that the assembly has been declared a Civil Disturbance. The announcement also must explain that if the identified violations are not corrected immediately, the assembled persons will be ordered to disperse.

C. Dispersal Orders

-

Dispersal Order. If the behavior that caused the Incident Commander to declare a Civil Disturbance does not cease after the announcement that a Civil Disturbance has been declared, the Incident Commander must issue a dispersal order. The dispersal order must include:

- Date and time;

- Number of times the dispersal order has been announced;

- Name and rank of the issuing officer;

- Statement that the officer is acting under authority of state law and that the assembly has been declared a Civil Disturbance;

- Statement of the basis for the designation of Civil Disturbance (i.e., which law has been violated);

- Clear order that all demonstrators present at the location shall disperse;

- Permitted direction of egress; and

- Statement that refusal to disperse may result in arrest.

-

Activating Body-Worn Cameras. Before the first announcement of the dispersal order to the assembly, officers must activate body-worn cameras, if not already activated.

-

Announcing the Dispersal Order. A dispersal order must be:

- Announced in a manner that is audible and intelligible to all persons in the assembly;

- Issued from multiple locations via an amplification system, where possible. Officers should be positioned at various points on the perimeter of the assembly, to ensure that the order can be heard clearly from locations within the assembly. If the Department does not have an amplification system available but the assembly is large enough that the order must be read from multiple locations to be heard by all persons in the assembly, multiple officers may read the dispersal order from different locations throughout the assembly;

- Issued in English and in any additional languages that may be appropriate based on the audience and the Department’s capabilities;

- Recorded by video or audio, with the time and the name(s) and locations(s) of the issuing officers(s) recorded in an event log; and

- Announced repeatedly, and at a minimum, at least twice, following the initial announcement, until the individuals in the assembly have dispersed, or until the Incident Commander determines that the individuals who remain do not intend to disperse and authorizes additional enforcement steps.

-

Reasonable Opportunity to Disperse. After the initial announcement of the dispersal order, officers must provide a reasonable opportunity for all individuals present to lawfully disperse, leaving the area by the designated egress route. Officers must continue to ensure that individuals leaving the assembly location have a clear route of egress to leave as directed while a dispersal order is in effect.

-

Kettling Prohibited. This policy prohibits the practice of police “kettling,” or surrounding a group to prevent them from leaving an area, except when the Incident Commander has authorized mass arrests as provided in this Policy, and probable cause exists to arrest each person in the encircled group based on officers’ observations of criminal activity.

-

Addressing New Assemblies. If individuals in an assembly disperse following a dispersal order and some or all of the participants re-convene at another site and engage in lawful, protected speech, the new assembly does not constitute a continuation of the Civil Disturbance. To treat the new assembly as a Civil Disturbance, the Incident Commander must make separate findings that the circumstances meet the definition of a Civil Disturbance and that a declaration of a Civil Disturbance as to the new assembly is justified.

D. Responses to a Civil Disturbance: Shows and Uses of Force

-

Shows and Uses of Force. After sufficient time has passed to allow compliance with repeated announcements of the dispersal order by all individuals who intend to comply, the Incident Commander may order additional shows or uses of force to obtain compliance from the individuals who remain at the site of a Civil Disturbance.

-

Department's Force Policies Apply to Civil Disturbances. The Department’s general policies regarding the use of force apply to all Department responses to Civil Disturbances. Officers maintain the same authority when responding to Civil Disturbances as they have during day-to-day police operations. The principle of proportionality, as described in the Department’s Policy on the authorization and standard for the use of force, applies in the setting of a Demonstration.

-

Verbal Warning. Unless exigent circumstances require immediate action, officers must issue a warning before any uses of force.

-

Consider Impact of Use of Force. In considering any use of force, an officer must consider the impact of the use of force on the dynamics of the assembled crowd, including the potential for further escalation in response.

-

Force Options Requiring Incident Commanders Authorization. Certain force options discussed in this Policy are permitted only with the authorization of the Incident Commander. For other force options, the use of force may be undertaken without the Incident Commander’s express authorization, if justified by the circumstances, but must be immediately discontinued upon an order by the Incident Commander.

-

Police Formations. Officers may use a police line as a passive show of authority to establish a barrier or encourage compliance (“constructive force”). In a police line engaged for the purpose of constructive force, officers do not make physical contact with members of the public. The police line has the goal of causing the movement of individuals or a crowd. Police lines may comprise officers in standard patrol uniforms.The Incident Commander also may determine that circumstances require the presence of officers wearing personal protective equipment, in response to violent activity or reasonably anticipated violence. When using and forming police lines, the Incident Commander, other supervisors, and officers must:

- Form police lines so as to leave an open path of egress from the Demonstration or assembly;

- Wear the appropriate Department-issued identifying insignia, regardless of the uniform they wear. Officers must not hide, disguise, or intentionally block their identifying insignia from members of the public;

- Behave neutrally and respectfully remains in effect in response to intentional provocation;

- Be aware of the risk that officers in a police line may experience personal reactions to the behavior of the people present at the assembly, including to statements or actions intended to provoke reactions from officers;

- Understand that officers in an organized formation do not have the same opportunity to remove themselves from the scene of a provocation, as do officers not engaged in a concerted show of force. Officers in a formation and their supervisors must be aware of any officers in the line who indicate an inability to maintain neutrality, and supervisors must coordinate a replacement for any such officer in the line;

- Consider the presence of officers wearing personal protective equipment to be an escalated response and may be perceived as such by the persons in the assembly; and

- Stage officers wearing protective equipment out of view until the Incident Commander determines that circumstances require their presence.

-

Using a Police Line to Forcibly Move Crowd Members. A police line also can be used to forcibly move members of a crowd in a predetermined direction.

- The use of physical force to move a crowd must be authorized by the Incident Commander, upon a determination that dispersing the crowd requires the use of this movement.

- The use of a police line to move a crowd will typically involve only bodily contact with the individuals being moved.

- If officers in a formation are directed to move the formation to shift a group in the assembly, and the officers are equipped with shields, batons, or bicycles, officers may be authorized by a supervisor to use this equipment to exert force on the crowd to be moved.

- If a supervisor authorizes the use of batons for this purpose, officers must hold the batons with a two-handed grip, in the port arms position.

- Any force exerted on individuals in the crowd must result from the movement of the police formation, rather than an officer’s independent manipulation of a weapon to strike, jab, or shove at individuals.

-

Batons. Batons may be used in a Crowd Control setting as follows:

- Officers may be authorized to use a baton to forcibly move members of a crowd in a predetermined direction as set forth in this Policy.

- Other than the use described in this Policy, any officer’s use of a baton must comply with the Department’s separate policy on the use of batons.

- Officers may not remove batons from their baton holsters unless directed to do so by a supervisor.

- The Incident Commander, supervisors, and officers must consider that the display of batons may be viewed by persons in the assembly as aggressive or intimidating and, therefore, an escalated response.

-

Canines. The Department prohibits the use of canine units for the purpose of Crowd Control.

-

Water Cannons. The Department prohibits the use of water cannons for the purpose of Crowd Control.

-

Kinetic Impact Projectiles (Rubber or Plastic Bullets) or Extended Range Impact Weapons (ERIWs). The Department prohibits the use of kinetic impact projectiles or ERIWs, including foam baton rounds and beanbag rounds, for purposes of Crowd Control and dispersal, and prohibits these weapons from being fired into crowds. When used against individuals for defensive purposes:

- An officer who is trained within the last year in the use of an ERIW may fire an ERIW at a single person for defensive purposes only, when the officer reasonably perceives that the use of this weapon is necessary to prevent an imminent threat of serious bodily injury to an officer or another person and proportionate to the perceived threat.

- An ERIW may not be aimed at the head or neck of the person. The Department considers an ERIW deployment aimed at the head or neck of a person to be a use of deadly force.

- An ERIW may not be deployed from a distance of less than ten feet from the person.

- For the safety of all persons in the surrounding area, before deploying an ERIW round, an officer should clearly announce that they are firing an ERIW.

- Generally, an ERIW should be fired once to gain compliance. If an officer fires once and is unable to obtain compliance, and the officer reasonably determines that additional shots are necessary, proportionate to the perceived threat, and the ERIW can be safely deployed, additional shots must be directed at different areas of the person’s body than the original shot, but not the head or the neck.

- An officer must ensure that a person struck by an ERIW projectile receives medical aid before being transported or released.

-

Long-Range Acoustic Device or Sound Cannon (LRAD). The Department prohibits the use of an LRAD’s “deterrent” or “alert” tone for purposes of Crowd Control or dispersal. However, the Incident Commander or their designee may authorize the use of an LRAD’s communication function for the sole purpose of communicating information to a large assembly, if the Incident Commander or their designee deems such use to be appropriate. Only officers trained in the operation of the LRAD may use an LRAD for this purpose.

-

Documenting Uses of Force. Officers must document and report all uses of force, regardless of type, outcome, and source of authorization, in accordance with the Department’s policies regarding the use of force.

-

Duty to Provide Medical Aid. An officer’s duty to provide appropriate medical aid applies in full force to the context of Crowd Control and crowd dispersal. In particular, officers must ensure that individuals who are impacted by the use of ERIWs, pepper spray or pepper balls, or chemical force (tear gas), receive appropriate medical attention.

-

Mass Arrests. The Incident Commander and officers should carefully consider the need for individual arrests during a demonstration. The Incident Commander should make officers aware that individuals who engage in unlawful activity during a demonstration may be identified and arrested at another time and place. Officers therefore may have discretion to delay or forgo arrests where there is no imminent public safety need to take the individual into custody and where an officer reasonably perceives that arresting an individual will have the effect of escalating crowd tensions, such that the benefits of a legally justified arrest are outweighed by the likelihood that the arrest would escalate tensions.

-

Authorizing Mass Arrests. The Department limits mass arrests to when authorized by the Incident Commander or the Chief of Police. The Incident Commander or the Chief of Police may authorize mass arrests only of individuals engaged in criminal activity that arises out of the assembly. The decision to undertake mass arrests must be supported by probable cause that each individual to be arrested engaged in a criminal act justifying arrest. Further, mass arrests should be undertaken only as a last resort, when all other reasonable options have been exhausted.

Before an Incident Commander or the Chief of Police may deem mass arrests to be necessary, all reasonable efforts should be made to:

- Issue citations for nonviolent lawbreaking activity that does not, on its own, justify arrest;

- Engage in individual arrests for arrestable offenses, subject to the considerations set forth above; or

- If a dispersal order has been issued, obtain voluntary compliance with the dispersal order.

-

Planning for Mass Arrests. To effect mass arrests that respect the rights of the individuals, the Incident Commander must engage in critical pre-planning.

- Although mass arrests should be used as a response of last resort, the Incident Commander should include plans in the pre-event written plan for the possibility of mass arrests if the Incident Commander has reason to believe that mass arrests may be required.

- If the Incident Commander does not contemplate mass arrests in the pre-event written plan, but the Incident Commander later becomes aware that mass arrests may be required, the Incident Commander should devise and issue a formal plan for mass arrests as soon as possible.

- The plan for mass arrests must include the designation of one or more processing locations that are adequately staffed and equipped to process arrestees expeditiously and administer required medical care.

- The designation of processing centers and the Department’s processing of arrestees must account for arrestees’ access to adequate bathroom facilities, food, and water.

- The mass arrest plan and operation of processing sites must account for the need to safeguard the personal property of arrestees, which may include large items such as bicycles. Personal property must be safeguarded in accordance with Department policies with the goal that all property shall be identifiable and returned to its owner upon release.

- If it is not feasible to establish adequate processing facilities near the Demonstration, the Incident Commander must ensure that adequate transportation is available to transport arrestees safely and without unreasonable delay to a processing center. If transportation is required, the transportation plan must account for arrestees’ access to adequate bathroom facilities, food, and water.

- The Incident Commander must coordinate with court staff and prosecutors as needed, to facilitate the efficient conduct of initial appearances and other post-arrest processes.

-

Mass Arrest Protocol. If the Incident Commander or the Chief of Police authorizes mass arrests, these arrests must be carried out by arrest teams, designated by the Incident Commander or a designee or through the Department’s normal procedures.

- Arrest teams must be informed of the basic offenses that form the basis for mass arrests.

- Each individual arrestee must be advised of the charge(s) and informed that they are under arrest.

- Each officer on an arrest team must be trained or informed in the safe and appropriate use of disposable (flex) handcuffs. If officers use flex handcuffs in a mass arrest, the flex handcuffs must be applied in accordance with the Department training. Flex handcuffs applied to an arrestee will be clearly marked with the badge number of the arresting officer, in permanent ink.

- Officers must follow a protocol, designated or approved by the Incident Commander, to identify each person arrested and record the following basic information about the arrest: date, time, location, and name and badge number of each arresting officer.

- Injured arrestees and arrestees who request medical attention must receive medical care without unreasonable delay and before any transportation.

- Before any transportation, each arrestee must be photographed, with additional photographs of any injuries. All property of the arrestee must also be photographed.

- The unit responsible for transporting arrestees must not transport an arrestee, whether for further processing or to a detention facility, without receiving (1) the photographs taken of the arrestee upon arrest; and (2) completed booking paperwork for the arrestee, or at a minimum, a record of the charges and the name and badge number of each arresting officer.

- Other than the procedures outlined in this policy, all arrests must be processed in compliance with the Department’s arrest and processing procedures.

-

Suspending Crowd Control Tactics Upon Voluntary Dispersal. If the Incident Commander authorizes Crowd Control or dispersal tactics, but the remaining crowd appears to begin to voluntarily comply with the dispersal order, officers must suspend such tactics.

D. Force Prohibited Against Passive Resistance

- Force Prohibited Against Passive Resistance. The Department prohibits the use of force against a person engaged in nonviolent, passive resistance, other than physically moving the person when it is necessary for that person’s safety or public safety. The physical moving of a person engaged in passive resistance may be undertaken only when all available efforts to obtain voluntary compliance have been exhausted.

- Individuals Intending to Be Arrested. Individuals engaged in passive resistance who make clear that their noncompliance with a dispersal order is undertaken with the intent to be arrested must be arrested, without first being subjected to additional uses of force or dispersal tactics.

E. Restriction on Use of Pepper Spray and Chemical Force

-

Oleoresin Capsicum Pepper Spray (Pepper Spray). The Department limits the use of pepper spray for crowd dispersal to when specifically authorized by the Incident Commander in response to a reasonably perceived need. The Incident Commander may authorize the use of pepper spray for crowd dispersal only when other means of obtaining compliance would be more intrusive or less effective. When the Incident Commander authorizes its use, any officer use of pepper spray must comply with the Department’s separate policy on the use of pepper spray.

-

Large-Volume OC Spray Canisters and OC Pepper Balls. The Department limits the use of large-volume OC spray canisters and OC pepper balls for crowd dispersal to when specifically authorized by the Incident Commander in response to a reasonably perceived need. The Incident Commander may authorize the use of large-volume OC spray canisters and OC pepper balls for crowd dispersal only when:

- Use is deemed reasonably necessary to prevent significant physical injury of police officers or members of the public, or to prevent significant property damage; and is

- Proportionate to the perceived threat; and

- Other means of Crowd Control must have been exhausted or the Incident Commander must reasonably believe that other means of Crowd Control would not be effective, before OC spray canisters or OC pepper balls are authorized; and

- When the Incident Commander authorizes their use, OC pepper balls must be aimed at the ground near a crowd or above the crowd, and not at individuals’ bodies.

-

Use of Pepper Spray Against Individuals in Crowd. An individual officer carrying a personal-sized pepper spray canister and trained in its use within the last year may use that spray to subdue a single person, but only when that force is necessary to protect the officer, the individual, or another party from imminent physical harm, is proportionate to the perceived threat, and where lesser means would not be effective. Unless exigent circumstances require immediate deployment, an officer must seek and obtain a supervisor’s approval before using pepper spray against an individual in a crowd setting. Any officer's use of personal-sized pepper spray must comply with the requirements of the Department’s separate policy on the use of pepper spray.

-

Chemical Force (Tear Gas). The Department limits the use of chemical force (tear gas) to when authorized in writing by the police chief or a designee.

- The police chief or a designee may authorize the use of chemical force only as a defensive tactic. Its use may be authorized only to respond to violent activity and to prevent an assembled crowd from engaging in further violent activity that presents an imminent threat of serious bodily injury to officers or other persons. The use of chemical force must be proportionate to the perceived threat and it must reasonably be perceived that no efforts to segregate and subdue violent actors by any other means will be effective.

- The Incident Commander must issue a loud verbal warning before deploying chemical force. The verbal warning must be sufficiently loud so that it can be heard and understood by the entire assembled group. If the crowd is assembled in an area where non-participating members of the public are likely to be present, the Incident Commander should make efforts to issue warnings to the public that chemical force will be deployed in the area. The Department’s official social media channels may be used for this purpose in addition to in-person contact with individuals in the area.

- Before deploying chemical force, the Incident Commander must ensure that routes of egress are available to the assembled crowd. The Incident Commander also must ensure that a sufficient number of officers and other emergency personnel, and sufficient supplies, are available to provide medical aid following the deployment of chemical force.

1.4 First Amendment Right to Record Police

A. First Amendment Right to Record

- Planning to Safeguard Exercise of First Amendment Rights. The Department’s response to Demonstrations must be planned and executed in a manner that facilitates the public’s exercise of First Amendment rights of speech and assembly. That response must take into account the public’s First Amendment right to record police.

- Right to Record Police Activity. Members of the public, including but not limited to members of the press, have a First Amendment right to record police officers’ activity in public places, so long as the person making the recording does not interfere with the officers’ official activity. A person who is lawfully in a public space or another location where they are legally permitted to be present has the right to record things in plain sight or hearing, which includes police activity that is observable from this lawful vantage point.

- Additional Officer Duties and Obligations. Officers must be aware that the recording of people, places, buildings, structures, and events is a common and generally lawful activity. Officers may not regard the act of recording, alone, as suspicious activity, when persons recording are in a place where they are legally permitted to be present.

- Assume You May Be Recorded. Officers should assume that they may be recorded at all times when they are on duty and in a public space. Officers may not threaten, intimidate, or otherwise discourage or interfere with the recording of police activity. Doing so may subject an officer to disciplinary, corrective, or legal action.

B. Limits on the Right to Record

-